Perseverance

and grit: the life and legacy of

Cecil B. Moore

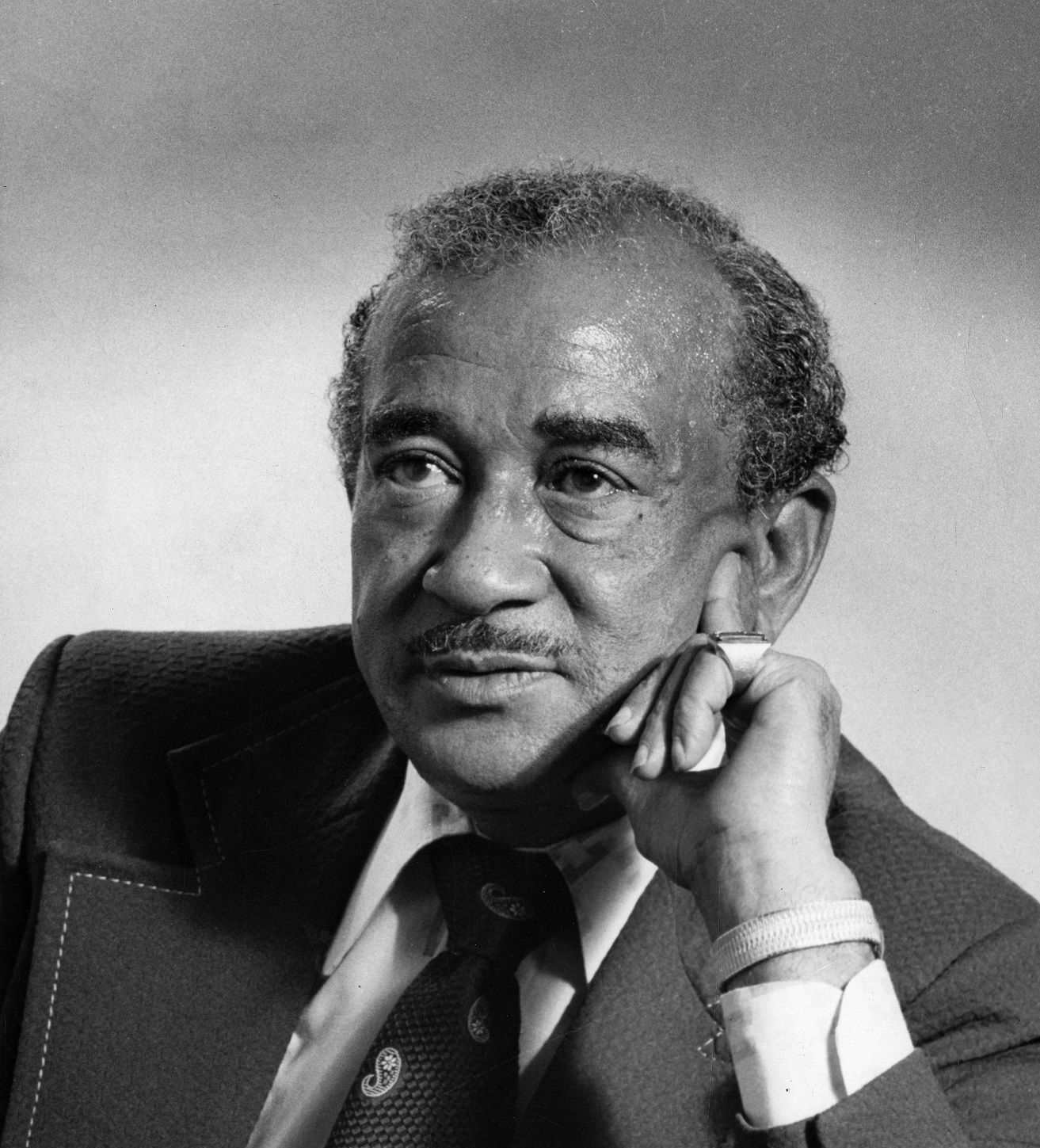

The history of the civil rights movement in Philadelphia cannot be written without Cecil B. Moore, LAW ’53. A skilled defense attorney, a former Marine and a powerful orator and leader, he fought for Black Philadelphians to have equal access to education, housing and jobs—to have the same rights and receive the same respect as their white neighbors.

He was born in West Virginia in 1915. The son of a doctor, he was brilliant, charismatic and proud of his roots. “My father was, as many men of that era, unapologetically himself,” said Alexis Moore Bruton, EDU ’76, Moore’s daughter. “He had no bones about letting people know that he came from a heritage of college-educated Black people, which for that time and place was fairly rare.”

Moore was also fastidious about his clothes, never appearing with a cufflink or tie bar out of place. “He was one of the most dapper dresses you’d ever want to see,” said Karen Jordan, a former youth member of the Philadelphia branch of the NAACP, the nation’s oldest civil rights organization. “His presence, his fearlessness, his bravery, the way he spoke—that’s what drew me to him.”

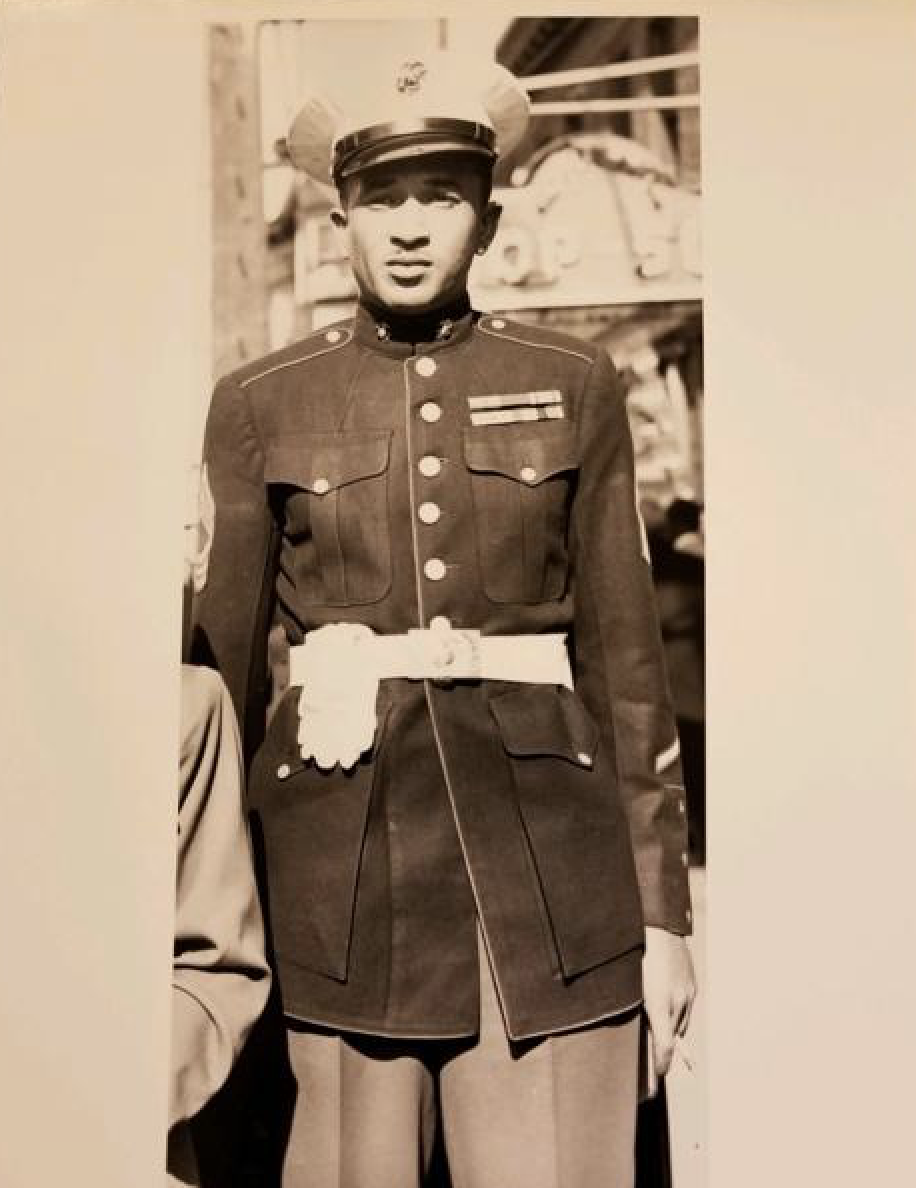

He joined the U.S. Marines in 1942 and was one of the Montford Point Marines, who battled racism and segregation to become the first Black men in the corps who were allowed to carry weapons and serve on the front lines. “My dad and his fellow Montford Point Marines were determined to be the best they could be and pass every test,” Bruton said. “They really and truly were patriots beyond belief, because when you think about it, those men fought for the right to die for their country.”

Moore fought in the South Pacific during World War II, seeing action in Saipan and Corregidor and serving in the peacekeeping force in Okinawa, before returning to the U.S. He eventually rose to the rank of master sergeant and was protective of the men under his care.

Bruton was told that a Marine her father supervised was once accused of assaulting a white woman. Moore believed he was innocent. “They [Moore’s white officers] hated talking with him. They hated knowing most of the time he didn’t show up unless he had a case or an argument to make,” she said. As Moore walked down the long corridor where his superiors had their offices, the doors began to close. “All these doors closed until the poor guy who was at the very end of the hall had no choice but to meet with my father,” she said. The Marine was later released.

When Moore was discharged from Fort Mifflin in 1951, he decided to settle in Philadelphia, briefly considering a career in medicine before choosing law. “If you were not scientifically minded, which he wasn’t, the options—especially for African American men to make money without being indebted to a white man—were kind of limited,” Bruton said.

Becoming a lawyer gave Moore the opportunity to earn an independent income and show his intellectual prowess. It also gave him the chance to secure rights for African Americans that he and other Black veterans felt were long overdue. “[He had] a deep and abiding belief that this country could and would live up to its promises, but only if we did it in the court of law and on the streets,” Bruton said.

He chose Temple because, as a North Philadelphian, it was almost on his doorstep. He also financed his studies by working as a liquor wholesaler, getting to know a broad cross section of people—experience that would serve him well as both a lawyer and an activist. “He had the right kind of charisma to connect in very visceral ways with everybody in the African American community,” said Cecily Banks, EDU ’76, the eldest of Moore’s three daughters.

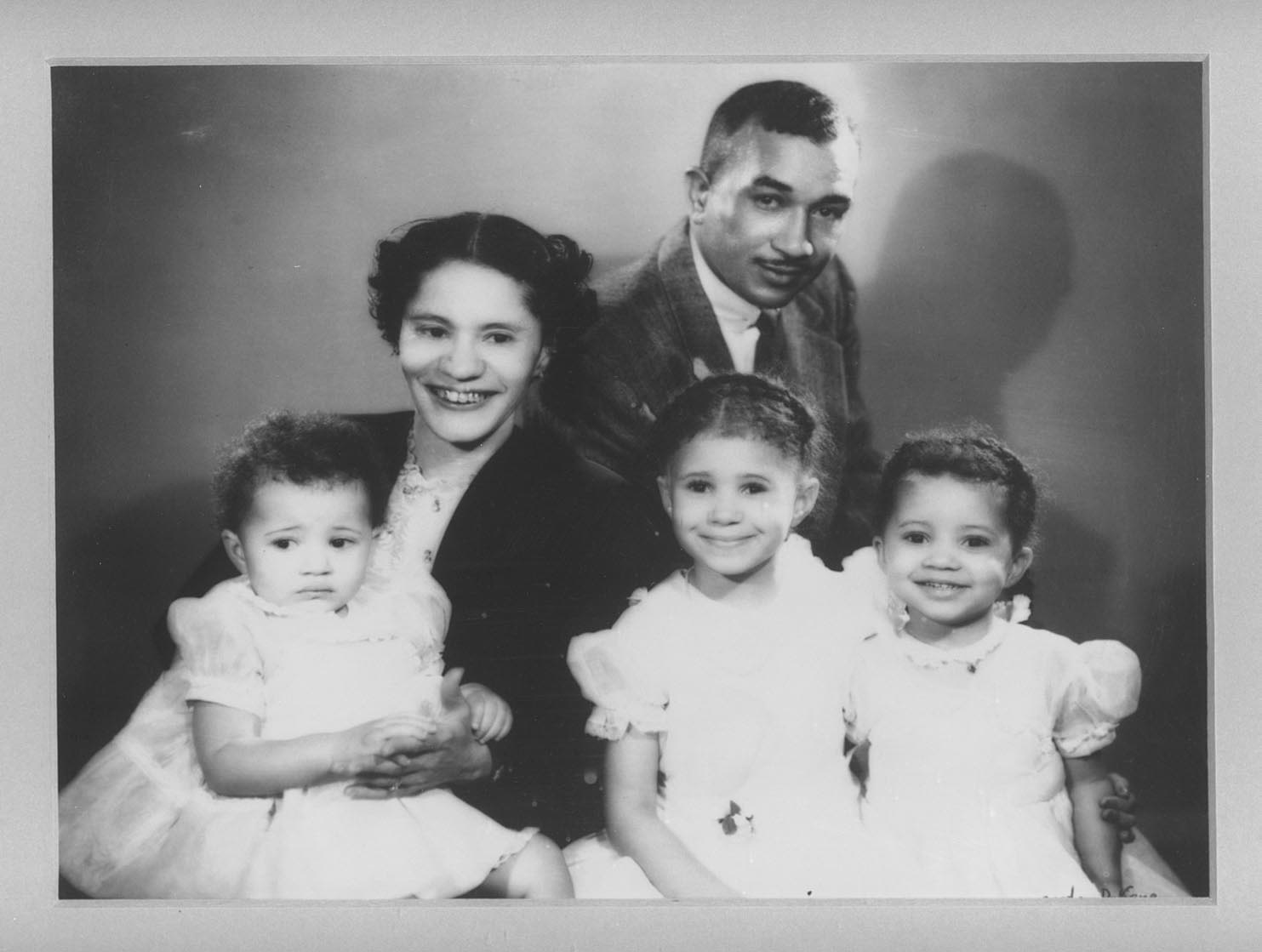

Photo courtesy of Cecily Banks.

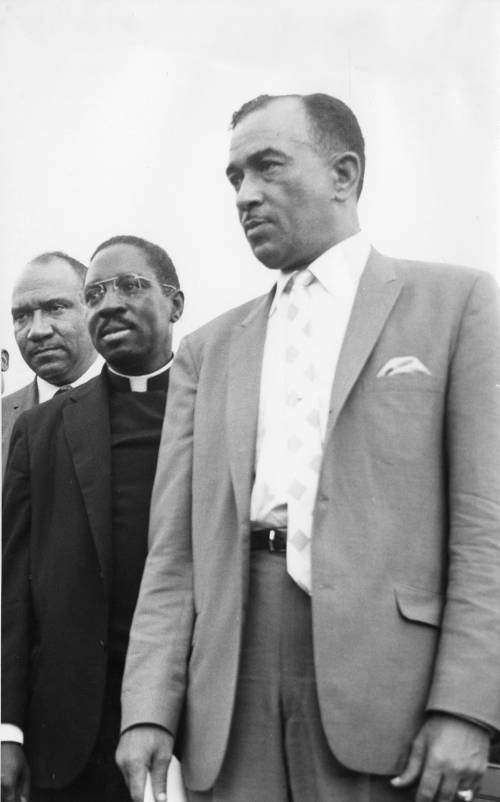

Photo courtesy of Cecily Banks.

The Moore Girls

A tough, no-nonsense negotiator and leader, Moore was also a gentle, loving father. He envisioned a future in which his three daughters—Cecily, Alexis and Melba—would have more options than he had had and he took their education seriously. “Because of the movement, I had choices in my life that many people did not,” Bruton said. “But to take advantage of those choices, I had to be prepared, above and beyond what the standard would have been for people who were not Black.”

The sisters, who were known in their neighborhood as the Moore Girls, grew up under the protection and scrutiny of a close-knit community that respected Moore. And although his work often kept him from attending their dance recitals and other events, he always heard about them. “He didn’t go to all that stuff but he knew about it, and that’s partially because the community was proud of him and wanted him to know his girls were coming along just fine,” Bruton said.

Moore quickly established a reputation as a gifted lawyer and his services were soon in demand. Jordan remembers seeing people waiting in line and sitting outside on the steps to his office, hoping they would get to see him and persuade him to take their case. “He did so many things for so many people without money, so no matter what, you got the best, most proficient legal defense,” she said. If a client couldn’t afford his full fees, Moore would sometimes ask them to bake him a pie instead.

He also joined the NAACP. At the time, Banks said, “there wasn’t any other organized group that had, at least on the surface, broader aspirations for [its] members.” In Philadelphia, the group’s membership was largely middle class. “They did not reach out to encourage participation by anybody outside of their little enclave,” she said, “so the memberships tended to be very small.” Moore also thought they seemed content to accept small gains piecemeal. “They were more polite about asking for what should have been given by right,” Bruton said.

When he was elected president of the Philadelphia branch in 1962, he decided to do things differently. He broadened the group’s membership and advocated for tactics that focused on getting more African Americans access to blue as well as white collar jobs. “That’s what real activism is about,” Banks said. “It’s connecting with the community. It’s setting expectations. It’s having goals that are focused on what people can see and hear and and are directly connected with, rather than just some kind of wild-eyed general idea of freedom.”

Under Moore’s leadership, Philadelphia’s NAACP would be more active and less passive. “Daddy didn’t believe in pulling punches with anybody: Black, white, brown, whatever,” Bruton said.

Moore was acutely aware of what he was fighting against. “The daily humiliations, now they call them microaggressions. There was nothing micro about being told, ‘We don’t serve you here. Leave.’ There was nothing micro about being forced to accept less than justice,” Bruton said.

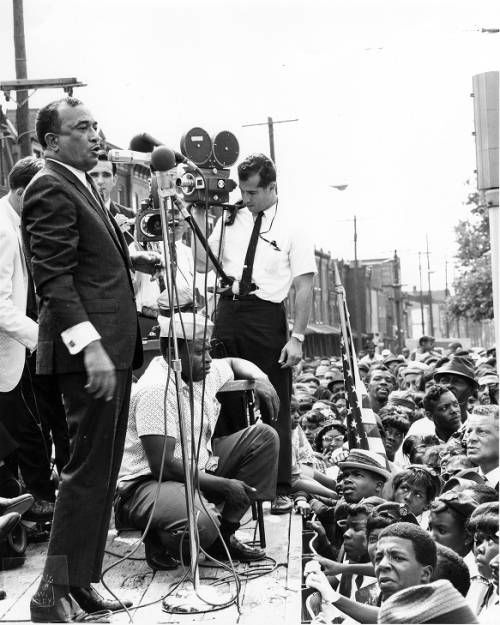

And Moore viewed demonstrations and protests as crucial parts of the NAACP’s arsenal. “He believed in direct action: if you’re going to discriminate, then we’re coming to you,” Jordan said. “He empowered Black people to stand up and not to fear, because our rights were guaranteed by the constitution of the United States and we weren’t going to let anybody take that away from us.”

He organized pickets to integrate public schools, to get Black workers admitted into labor unions, to stop businesses who received federal contracts from discriminating against Black employees and to ensure that Black postal workers were treated fairly.

In 1965, he turned his attention to Girard College, an independent boarding school in North Philadelphia. Built in 1833 at the behest of Stephen Girard—a Philadelphia merchant and philanthropist who wished to found a school for poor, white, orphaned boys—the school remained segregated, even as the neighborhood around it became home to a burgeoning African American community. Moore organized demonstrations outside the college, demanding desegregation.

That’s how Jordan first met him. Her family lived close by—so close her aunt could see Girard College clearly from her window—and one morning, Jordan and her friends decided to walk over to the college and take a look at the protests. A few policemen spotted them and began to harass them. “We got to the front of Girard College and I said, ‘I’m going to tell Mr. Moore.’ I knew him and read about him, because we always had the newspapers,” Jordan said. She walked up to Moore, explained what had happened and watched as he immediately leapt to her and her friends’ defense.

Impressed by Moore’s response and by what the demonstrators were trying to achieve, Jordan joined the protests. She was just 16 years old. “He gave you hope. He empowered you. He made you embrace that fight for freedom,” she said. The protests lasted seven months. “We had the whole summer. That’s why we could be there. And a lot of people that I met on the picket line are the people that I’m friends with today,” she said.

The demonstrations ended in December, after the city of Philadelphia filed suit against Girard College’s admissions policy. Girard was ultimately desegregated in 1968. “With Cecil, when he did things, people saw instant results. You didn’t have to wait 20 or 30 years, as it seemed that we had to wait before,” Jordan said. “He let people know you can get things done. If we stuck together, we could do it.”

Moore and Martin Luther King Jr.

Moore’s confrontational style made him a celebrated figure, but also a controversial one. When activists invited Martin Luther King Jr. to Philadelphia in August 1965, they bypassed Moore, who respected King but didn’t share his belief in complete nonviolence. “That was the biggest thing,” Jordan said. “He was a military man and he did not believe in that. Neither did we. We were not violent, but we believed in self-defense.”

There was considerable friction between the two men’s supporters. But whatever their differences in approach, Moore and King worked together during the Girard College protests, addressing the crowd of demonstrators.

Banks believes her father’s form of activism was aggressive, but not violent. “I think [he] was focused on making it clear that we were not supplicants. We had full rights and those rights needed to be recognized,” she said.

Civil rights protests were effective, but they were also risky. “Folks want to soften the history of that period. It was dangerous. Which is why the organization of it, the significance of it was so important,” Bruton said. Jordan was once passing the Pennsylvania State Office Building when she saw a confrontation between policemen and protestors she knew. She rushed over, afraid one of her friends had been badly injured. She was arrested and later, after she was released, she was fired from her first job. Yet all the hardship was worth it. “We used to have a saying: we would follow Cecil B. Moore to Hell. It didn’t mean we were going to stay. But we would follow him there. And it’s because we believed in him,” Jordan said. “And he knew and we knew he had your back. We knew we could depend on him and he could depend on us.”

Eventually, Moore’s approach proved too controversial and in 1967, the national NAACP voted to split the Philadelphia branch into smaller branches, with Moore as the president of the North Philadelphia one. His authority was significantly lessened and he was removed from office that July. “People didn’t like the way he did business,” Jordan said. “They thought he was too powerful [and] he didn’t do things the way they wanted to.”

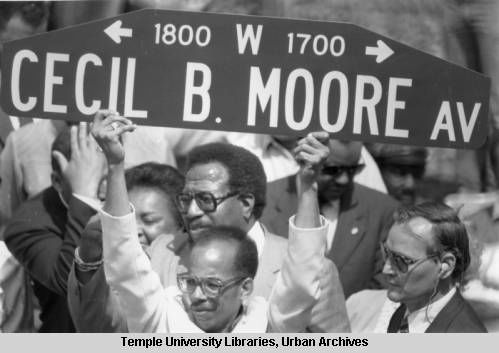

Nevertheless he remained extremely popular in the Black community and inspired dozens of lawyers, activists and politicians, including William Herbert Gray III, who represented Pennsylvania’s second congressional district for over a decade. “The first Black political class that rose out of Philadelphia [after the civil rights movement] is directly connected to my dad, no question about it,” Bruton said. “And I’m proud to say that there are Black lawyers everywhere, not just in Philly, who became inspired by seeing my dad in the courtroom.”

Moore also had a significant impact on the lives of Jordan and her fellow activists, who call themselves the Freedom Fighters. Jordan carried the spirit of her work with Moore with her, becoming a nurse and serving her community for more than 40 years. “I think he was one of the greatest men around, flaws and all,” she said. “I tell people, when you talk about Jefferson you don’t talk about the bad things that he did first. You talk about the good things he’s done.”

Cecil’s People: The Freedom Fighters

A Temple Made film about Cecil B. Moore and his supporters

“The power of the recorded materials spoke to the importance and the need to tell this story,” said Jonathan Shafer Kohl, TFM ’13.

He’s the director of Cecil's People: The Freedom Fighters, a short documentary telling the story of Temple graduate, lawyer and civil rights activist Cecil B. Moore and his closest supporters, known as the Philadelphia Freedom Fighters.

Kohl is also part of the 2020 class of Temple 30 Under 30 honorees, celebrated for being a media and entertainment visionary.

He joined History Making Productions, a Philly-based film company, as they began production on a new series, Philadelphia: The Great Experiment. In the team’s gathering of historical content, Temple’s Special Collections Research Center served as a vault of ephemera.

“It was almost like treasure hunting. You would find these 60mm rolls of film wound around a pencil with masking tape, which was like 60 years old and falling apart. On the masking tape there would be written one word, such as ‘Cecil’ or ‘Moore’ or ‘College’ and through that we found protest footage, rallies and speeches,” said Kohl.

Over the years, Temple curated a broad range of memorabilia from Philadelphia’s past. Along with this initiative, the university captured oral history from Philly’s Freedom Fighters, which inspired the three-part episodic series, Cecil’s People: The Freedom Fighters.

“Between KYW Channel 3 and the bulletin newspaper photographs from the libraries, the film was made up of about 95% of material from Temple,” said Kohl.

By exploring these archives, Moore’s story broadened the film crew’s perspective as they realized the weight of his impact and the lost moments of his legacy.

Cecil’s People screened at Cristo Rey High School, where students were immersed in the powerful transfer of oral history.

“The lights went out and the video began to play, and the high school kids started singing at the top of their lungs. They knew the words from the first two parts of the film. And they were stomping on the floor and clapping and singing. This is exactly why we had to make this, not to be on Netflix, which it isn’t, but we made it for the purpose of preserving their history and songs,” said Kohl.

The moment Kohl experienced at that high school stresses the importance of public libraries and accessible history. He also shares that his kind of work can build bridges from ancestors to communities, which can foster a greater understanding of who we are and how we arrived here. As for North Philadelphia and Temple history, Moore was monumental in its shaping.

“These events might not have ended up in the history books like Selma or any of these other moments in the Civil Rights Movement,” said Kohl. “But unearthing the materials and unearthing the history is part of the importance of getting it there.”

Moore died in 1979 at the age of 63. Bruton feels that the Black Lives Matter movement and the efforts to organize Black voters in the 2020 U.S. presidential election both show that people are still working toward progress, still inspired and determined to make the world a better place.

That thought fills her with hope. “I do know that it’s there and it’s going to be there and it’s going to be built on the spirit that my dad exemplified,” she said. “We will overcome. We have overcome. We are going to keep overcoming and we’ll all hold on to it. Every time they make us slip back, we climb back up.”