Being there

“Look around,” says Chris McAdams, assistant professor of architecture. “Look at how beautiful the city is from up here.”

Joanna Kozole, TYL ’19, turns her head to take it all in. Perched as they are five stories up on one of the city’s main thoroughfares, the floor-to-ceiling windows certainly offer a gorgeous panoramic view of Philadelphia. It’s breathtaking.

But Kozole and McAdams are not standing on the top floor of the city’s newest edifice.

Instead, the pair are in the architecture studio in the Tyler School of Art and Architecture on Temple’s Main Campus.

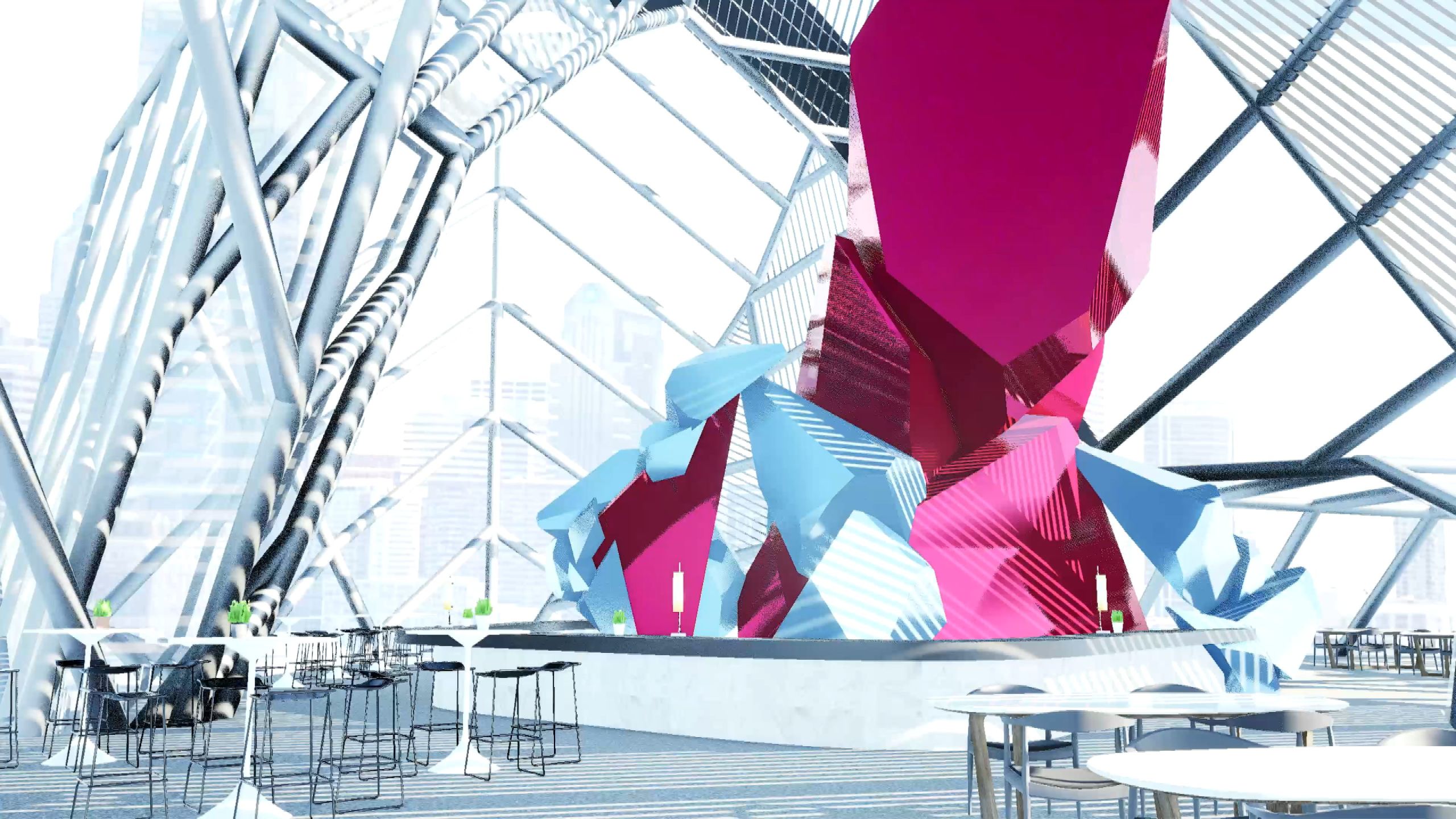

They are gazing out across the skyline from within an expansive glass atrium that Kozole and project teammates Jillian Carlisle, TYL ’19, and Marly Mikovitch, TYL ’19, constructed in virtual reality.

It was all part of the assignment in McAdams’s 2019 architectural design senior capstone: Design a new performing arts center on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway near 22nd Street.

McAdams is known for helping students use the latest technologies, including virtual reality (VR) platforms, to create their spaces and enhance their designs.

“In architecture, we ask students to work diligently for 15 weeks to create elaborate spaces and reimagine what a library or a school or a house could be; ultimately they make beautiful drawings and models, but that is traditionally the limit of their exploration,” says McAdams.

“VR allows them to go inside their structures and look around—these are special moments—it’s incredibly gratifying to be there in the space you’ve designed.”

Or not.

Says McAdams, “Sometimes a student may think their drawing is great and then they put on the headset, walk in and realize what they’ve created really doesn’t work, at least not the way they want it to.”

But that’s an opportunity to make a correction, he says.

An emerging trend

The ability to make corrections early in the design process is one reason VR is beginning to take hold in the architecture profession.

“When I was in school, professors were slow to adopt such technology and reticent to take it seriously,” says McAdams, who in 2017 founded Plural Architecture Studio, a firm devoted to helping architects use emerging technologies in their practice. “Today, leading firms recognize the design potential VR provides.”

So his students could get a first-hand look at how architects are using VR in their practices, McAdams took his capstone students to visit a New York City firm known for using the latest technology in their work: Mancini Duffy. During the visit, the Mancini Duffy team described a time when a client who was a chef walked into the virtual kitchen the firm had designed and recognized right away that there were opportunities to reconfigure the design and create a more efficient layout.

Identifying issues like this early in the process can save time and money, explains Michael Kipfer, who spearheads research and development efforts at Mancini Duffy. “In the virtual arena, we can interact with clients in real time during the design process and make appropriate changes.”

Lindsay Loftin Rule, a landscape architect and senior associate at PORT in Philadelphia, agrees that VR is invaluable in professional practice.

“It allows me to understand what my design will look like 10 years from now, when planting has matured and the spatial quality of a site is different from the day it is installed,” she says. “This kind of insight enables me to make better choices up front.”

Where tech meets tradition

While McAdams is at the forefront of using emerging technologies, including VR, in architecture curriculum, he still relies on traditional teaching methods in order to round out the educational experience for his students.

“Drawing and sketching allows everyone to quickly conceptualize a project before we jump into 3D modeling,” says McAdams. “I find it is critical that we take that early step so that each student can understand their design strategy before using VR to provide feedback and enrich the architectural experience.”

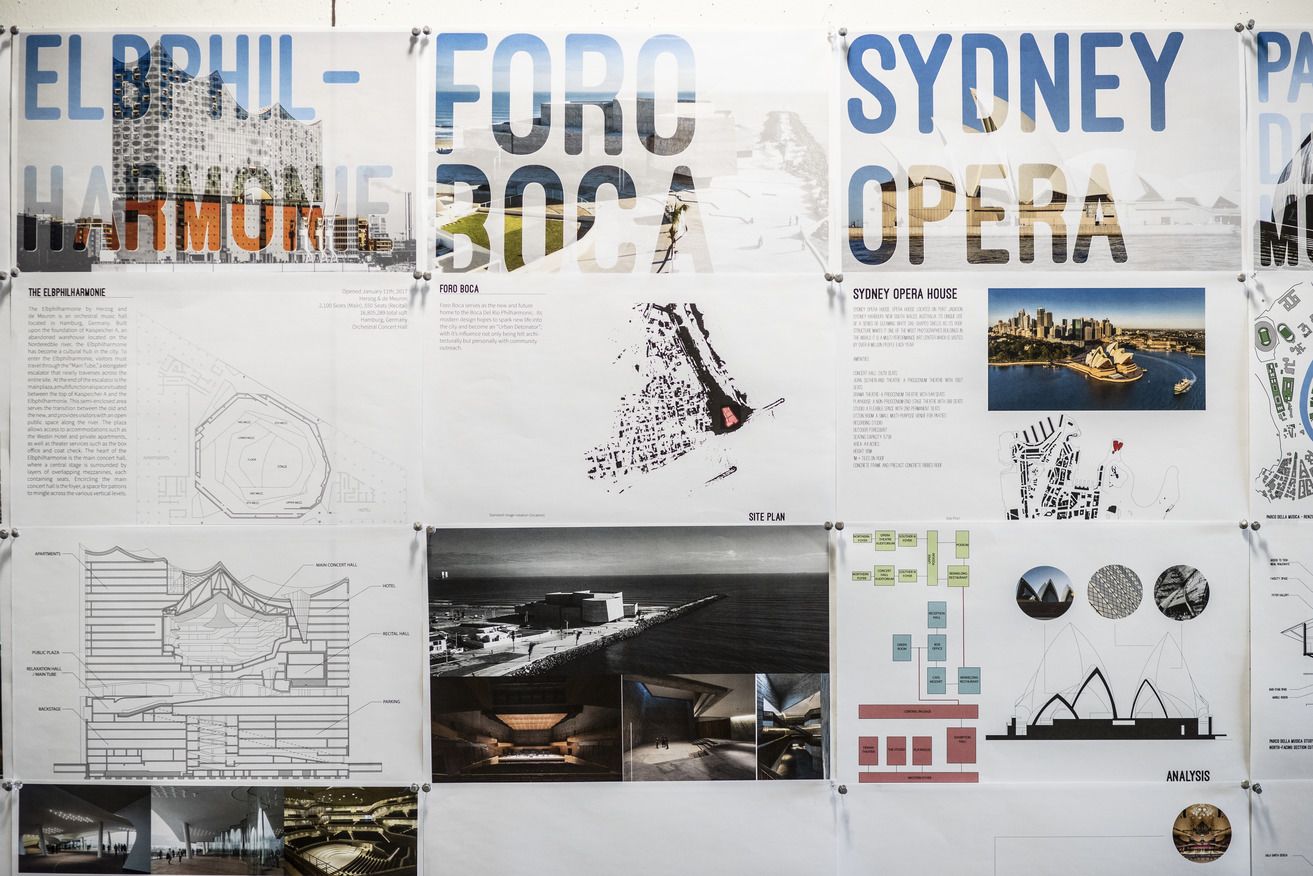

To inspire his students as they embarked on their capstone assignment, he showed them photographs and renderings of iconic theaters around the globe, including Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie, the Sydney Opera House, Rome’s Auditorium Parco della Musica and the Guangzhou Opera House.

Field trips to New York City’s Lincoln Center and one of Philly’s newest venues, The Met, exposed the students not just to the public areas of entertainment venues, but also to backstage rooms, loading docks and even parking garages. All of these behind-the-scenes details had to be accounted for in the students’ designs.

“The trips proved key to comprehending the details,” says Tinashe Chikomo, TYL ’19, who is currently working at Kimmel and Bogrette, a mid-sized firm in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania. “Understanding what our project needed, such as a driveway in back for dropping off equipment efficiently, is tied to the legacy left behind by projects that have addressed issues and demands similar to ours.”

The class even scoped out the actual proposed location for their venue, positioned next to the Rodin Museum and catty corner to a Whole Foods. They noted that the site currently serves its surrounding neighborhood as a popular park—providing the community with both a softball and a baseball diamond as well as swing sets and a playground.

“When we saw what the site was currently used for, my group decided we wanted to continue that aspect and create a space that was welcoming and accessible to all walks of life,” says Chikomo. “With this in mind, we committed to a design that would allow for a lot of public access.”

A powerful tool

I realized I didn’t fully understand my own design until I was inside of it. —Jillian Carlisle

For their project, Kozole, Carlisle and Mikovitch proposed a venue consisting of a series of performance spaces and combined public areas interconnected by a large, crystal-shaped atrium. “We embraced the extravagance of the assignment and created ornate forms and shapes in our design,” explains Carlisle, who is now employed with Wyant Architecture in Philadelphia.

The group’s multilevel glass atrium connected a café, commercial retail space, galleries and an entry to an outdoor green roof. The top level of the atrium was designed as an open viewing space with a central café wrapped around a lightwell that looked down to the floors below.

“Being able to experience our design spatially really broadened our understanding of our own work—I realized I didn’t fully understand my own design until I was actually inside of it,” says Carlisle of the VR experience. “It’s pretty simple to imagine a 10-foot high ceiling if you design a rowhome. But there’s a lot more complexity and confusion in imagining a complex, crystalline chamber 80-some feet in the air.”

And, it was while standing on the third floor of that chamber looking out across the city—virtually speaking—that McAdams and the team realized that some of the support structures within the café were limiting and in some cases obstructing the patrons’ views.

“Because we were able to experience firsthand what the problems with the design were, we were able to run through multiple options to correct it quickly,” says Kozole, who is currently a student in Tyler’s master of architecture program. “The process was iterative—we could experience the structure in VR and then make revisions to the design and then go back and see how our changes worked.”

Seeing is believing

Whereas VR played a critical role throughout the semester-long capstone in helping the students revise and enhance their designs, it was equally helpful at the final presentations when the student teams were tasked with communicating their design strategies to a panel of outside reviewers—instructors, stakeholders and practitioners whom McAdams invited to critique the students’ projects.

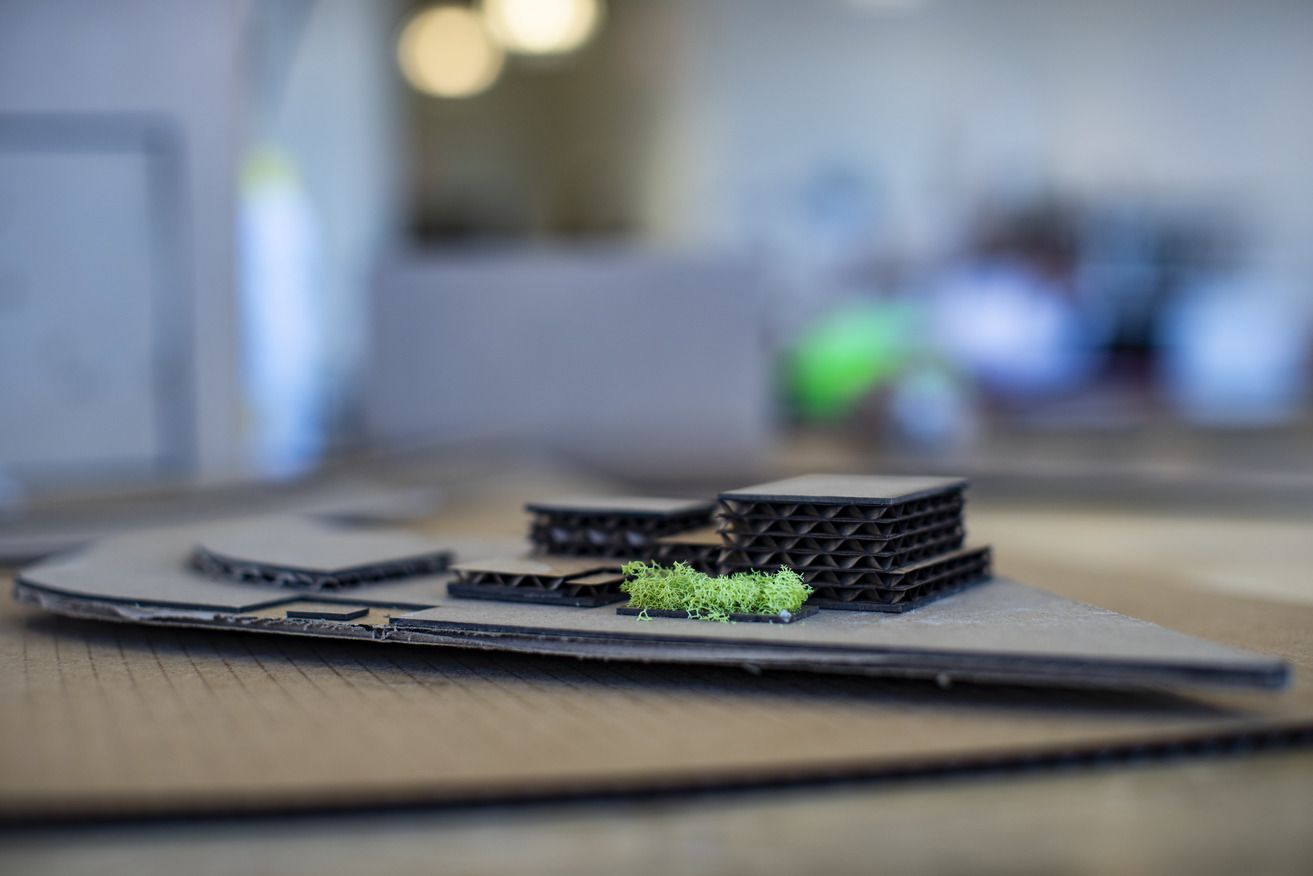

Each group presented their designs in a large, detailed 2D drawing and a 3D physical model, in addition to showing their structure in VR.

“Using VR in the design review allows the students, faculty members and outside guests to explore the spaces in full scale in a wholly immersive way—they can actually experience the material choices, the lighting and shadow qualities and the flow from one space to the next,” explains McAdams.

The VR platform enabled Rule, who served as a guest critic, to acquire a better grasp of the students’ design intentions. “As an external reviewer, you can only rely on the information given to you at the time of the presentation—so when information is ambiguous or incomplete, it is very hard to give constructive feedback,” she says. “In this studio, VR was the great leveler, with each student having the opportunity to present their architecture as it was meant to be seen.”

For Rule, one project in particular stood out in her mind. “It was the lobby space of a theater, and the students were determined to have a gold, shiny ceiling,” she says. “This is very difficult to represent in a static, 2D rendering—but in VR, that gold ceiling sparkled.”