Byte-size Books

Digitizing Temple University Libraries' science fiction collection

At Temple, the next frontier of print is digital. Librarians at Charles Library are digitizing hundreds of sci-fi books, preserving them in a new format and making it possible for researchers to analyze more books than they would ever be able to read at once.

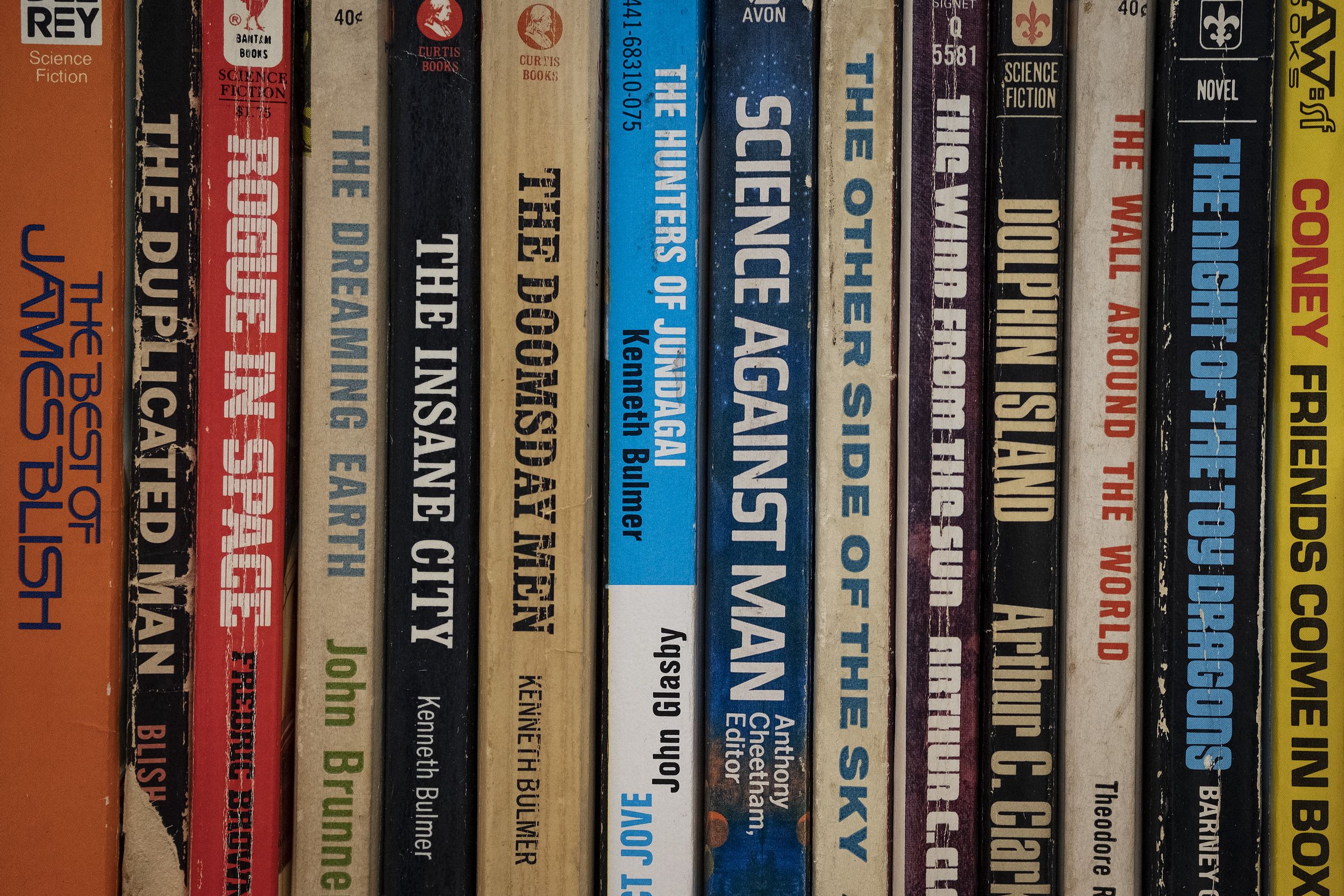

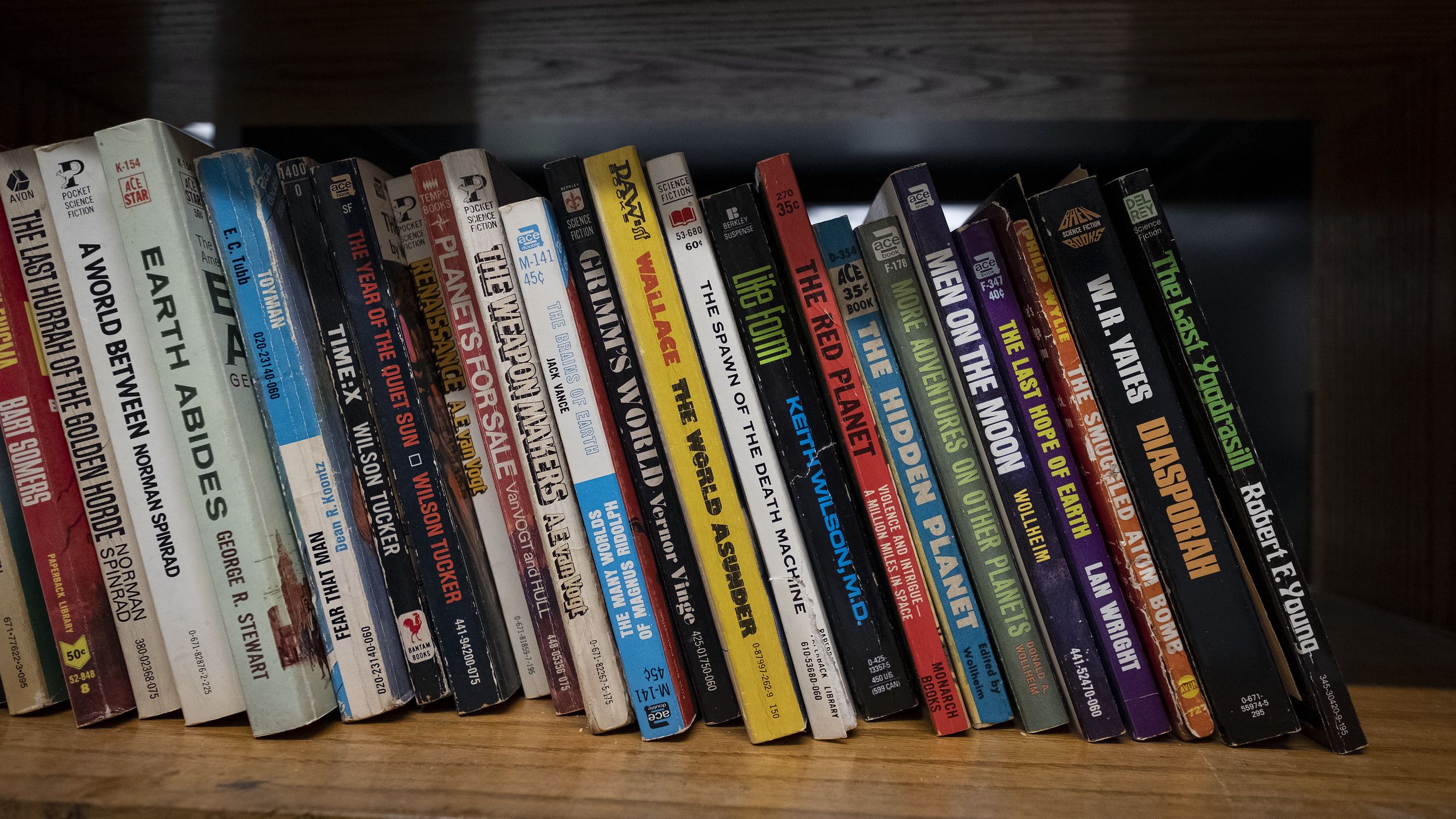

The books are part of the Paskow Science Fiction Collection, which was founded in 1972 when the family of David Paskow, EDU ’69, ’71, donated 5,000 sci-fi paperbacks from his personal library to the university. The collection soon expanded to include other material that might not last long if it wasn’t archived—magazines, posters and personal papers—and branched out to incorporate fantasy.

The collection reflects Temple’s commitment to preserving what might otherwise be overlooked, said Margery Sly, director of special collections at Temple University Libraries. “Since the ’60s, [Temple has] been interested in documenting contemporary 20th century modern movements, which is somewhat unusual for rare books and special collections,” she said.

As the collection grew, so did its number of duplicate books. When Sly and her team began the transition to Charles Library, they were confronted with 120 boxes of duplicates they no longer had a use for. Alex Wermer-Colan, a postdoctoral fellow at the libraries’ Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio, jumped at the chance to digitize them.

American culture has used sci-fi “as a field within which to imagine the future,” Wermer-Colan said. “And to imagine how the present could be different if the past had gone differently.”

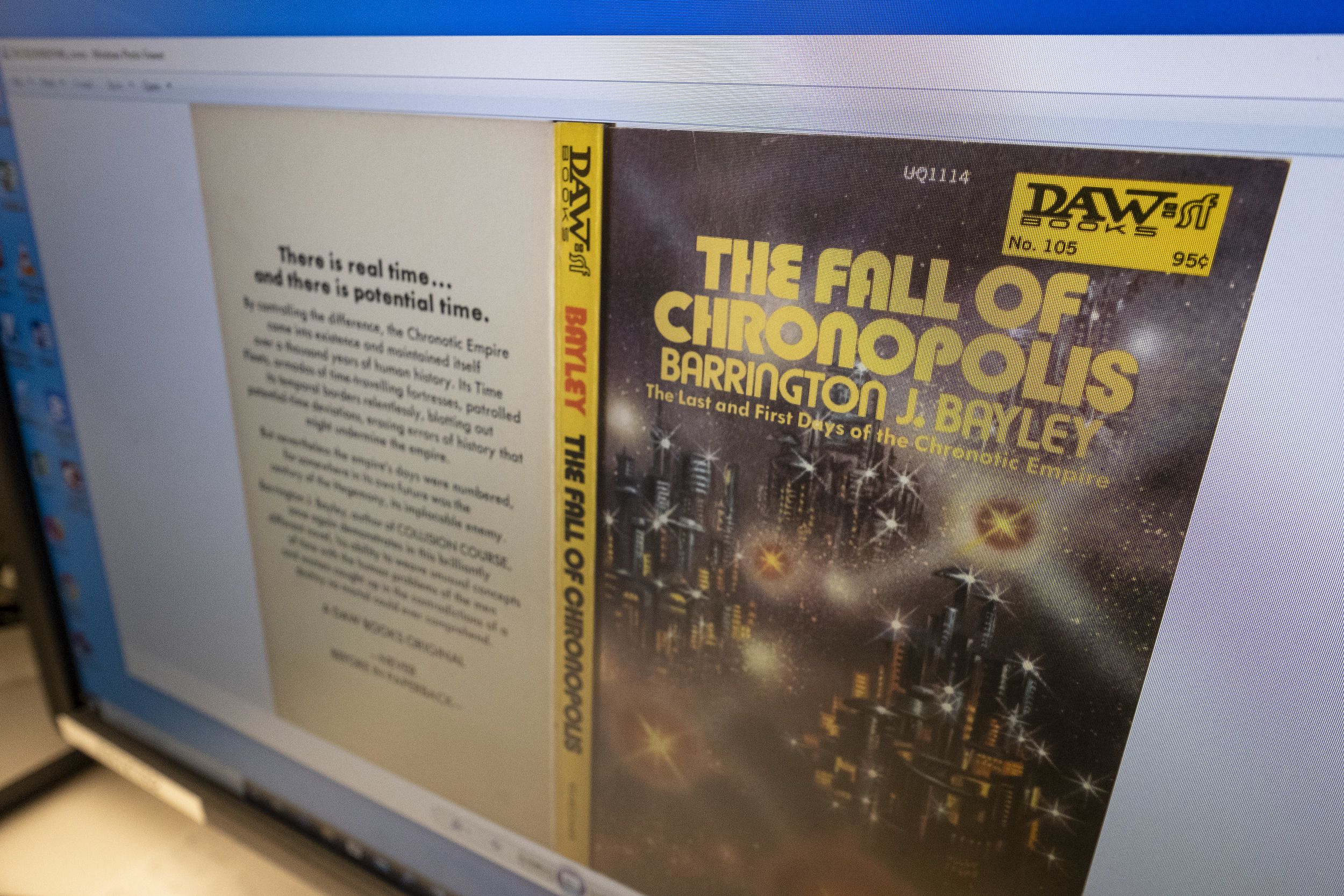

Digitizing a book means not only scanning its pages, but also running them through Optical Character Recognition, a process that transforms images into text. “Once you have converted the text into data, there are a lot of things we can learn about texts that we can’t by reading them,” Wermer-Colan said.

Counting how often certain words appear in a book, for example, can help determine who wrote it. J.K. Rowling was revealed as the author of The Cuckoo’s Calling partly based on computational analysis.

“No single human being or even a small group of human beings could ever read all of the books in existence,” Wermer-Colan said. So researchers have developed methods including distant reading, which uses computers to analyze texts.

But there are drawbacks. “It’s very difficult to draw conclusions about something like how the novel has changed if we only have a small subset of all the novels that were published,” he said.

That’s where the Paskow duplicates come in. Scholars have largely focused on digitizing books already recognized as significant literature. Genre fiction, including sci-fi, has often been regarded as low brow and pushed to the margins of the literary canon. Digitizing the Paskow books would help draw researchers’ attention to work that has been ignored.

Wermer-Colan and a group of graduate students sorted through 100-linear feet of books, exploring the history of sci-fi as they went along. “There was no really efficient way to do it except to just go from box to box,” he said. “We never knew what we would find.” They researched titles, filtered out books from other genres and kept a few that overlapped with fantasy and horror.

“We tried to be very open to not letting our own biases stop us,” Wermer-Colan said. “If we found a book that seemed absurd that was actually a good reason to keep it.”

Eventually they whittled the selection down to around 1,500 books and magazines, many of them published between 1960 and 1980, during sci-fi’s New Wave.

The New Wave

Science fiction took off as a genre in the early 20th century, with the rise of pulp magazines and stories about aliens, space exploration and new technology. After the second world war came sci-fi’s New Wave, “when writers began to try out new storylines, tell stories from new perspectives [and] use new styles of writing,” said Alex Wermer-Colan, a postdoctoral fellow at the libraries.

New authors, including women and people of color, began writing for an audience that was more varied than it had ever been before. “The New Wave is what has given birth to the much more diverse science fiction field that exists today, from indigenous science fiction to Afrofuturism and cyberpunk,” he said. It’s also the period the Paskow Collection specializes in.

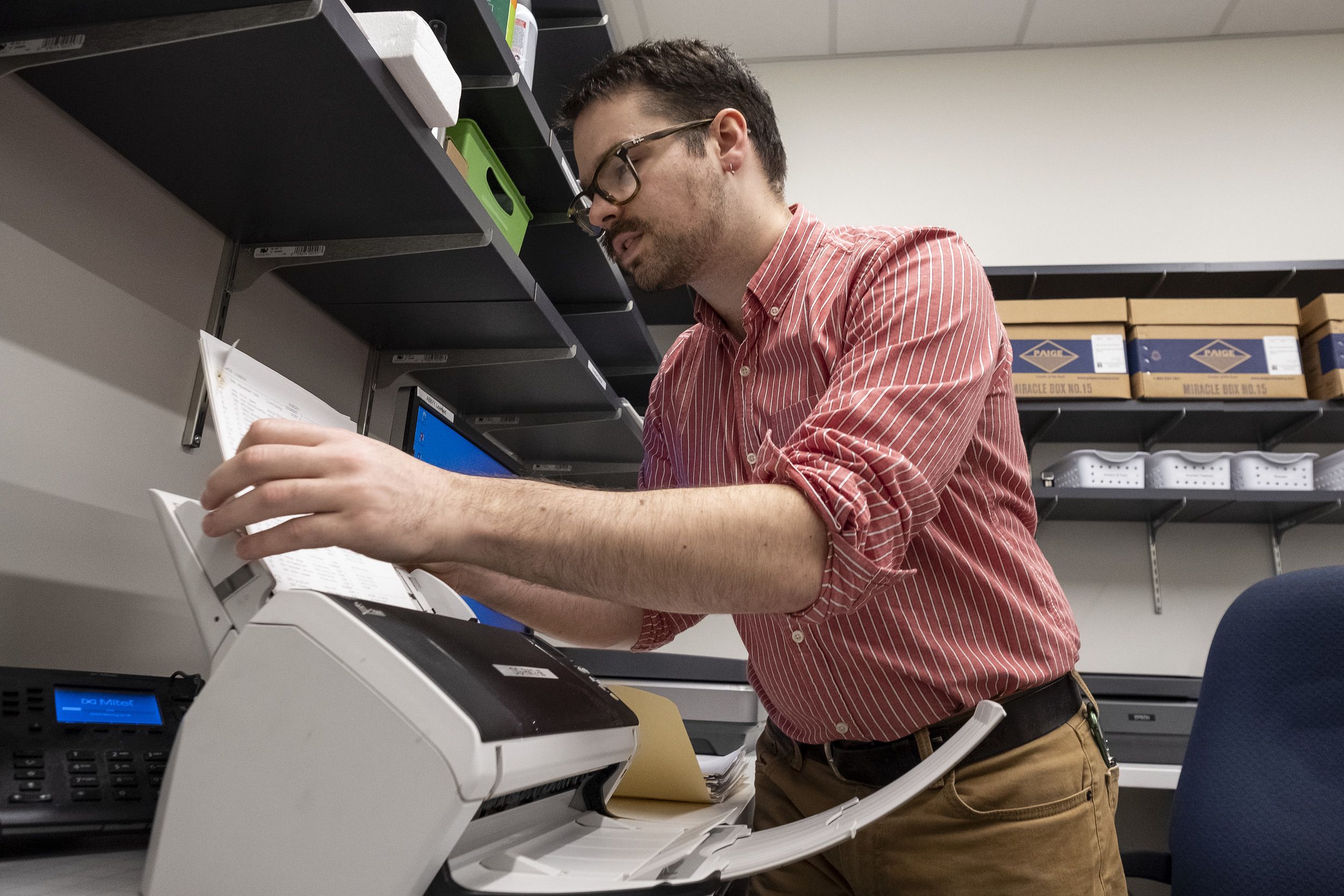

Metadata and Digitization Services has been scanning the books in batches. First the bindings are cut off, leaving a block of text that’s run through a sheet feed scanner.

“Cutting the bindings off is an imperfect thing,” said Bibliographic Assistant Michael Carroll. “[Publishers] try to fit as much text as they can on as much of the page as they can, so it goes all the way into the spine and it’s almost impossible to maintain the full page without sacrificing some of it in some scenarios.”

The next step is preservation. “Although it’s nice to think that all digital content is preserved forever, that’s not true,” said Digital Projects Librarian Stefanie Ramsay. “It’s a set of activities that we employ to make sure that that material can be accessed at a later time.”

Books as data

Temple Libraries’ Scholars Studio can’t provide researchers with digitized books in their entirety, due to copyright restrictions, so Wermer-Colan curates the data or corpora. “If they want to do topic modelling, what they need to know isn’t the order [in which] words appear, but how frequently words appear in the book,” he said.

“Working with the Scholars Studio’s graduate students, we developed methods to tag a book by chapter and tell the computer to split it into separate text files with disaggregated data,” Wermer-Colan said. Then they can share with researchers how many times each word appears in each chapter, so they can analyze and model the data.

The digitization project is “a way we contribute to the generation of new knowledge and illustrate the way that the sources in our holdings can be used for a variety of projects.”

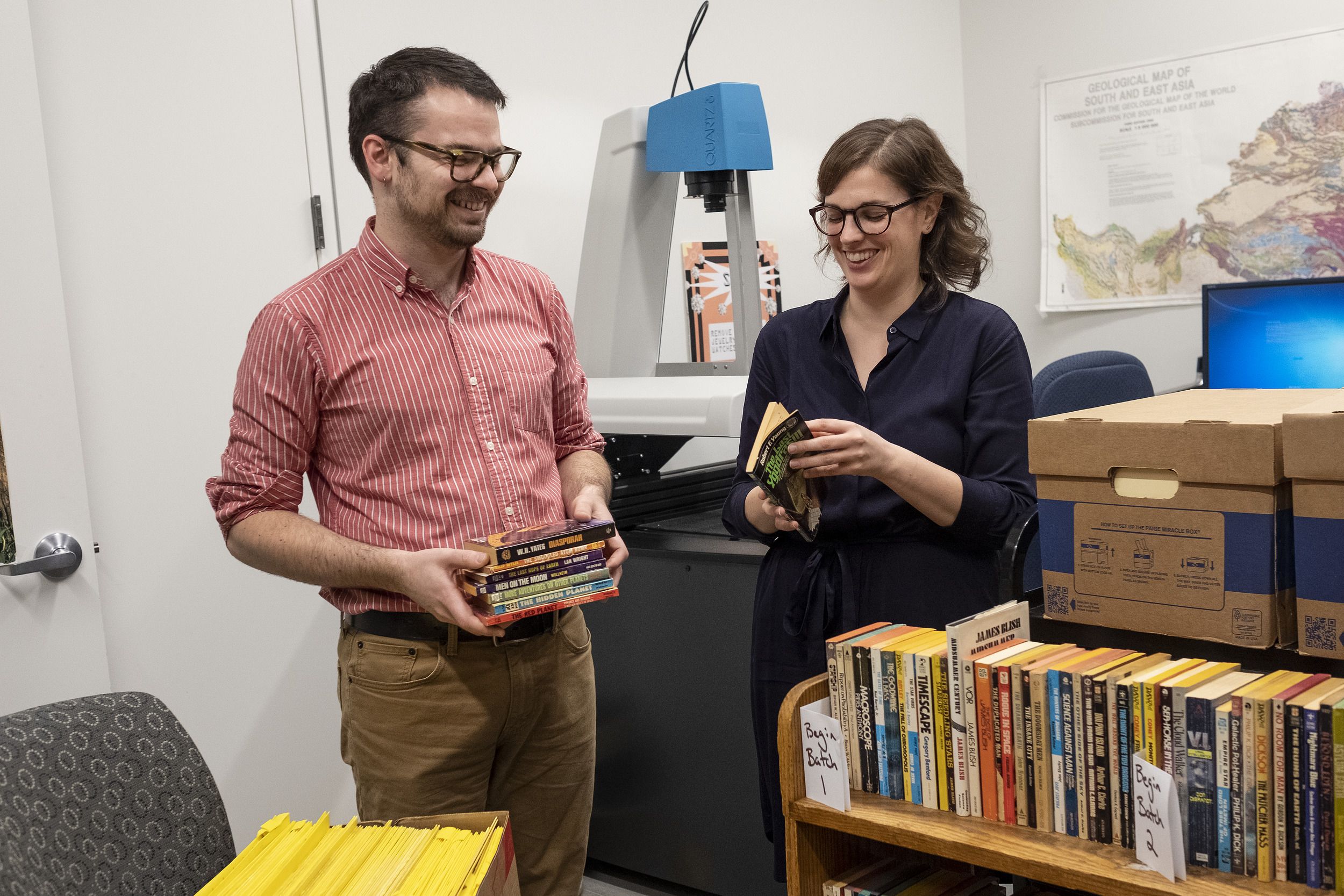

Michael Carroll and Stefanie Ramsay in the Metadata and Digitization Services office. It takes 30 to 40 minutes to scan a book. Many of them are printed on cheap newsprint paper, which crumbles easily, and with ink that smudges, building up a residue on the scanner that needs to be cleaned regularly.

Michael Carroll and Stefanie Ramsay in the Metadata and Digitization Services office. It takes 30 to 40 minutes to scan a book. Many of them are printed on cheap newsprint paper, which crumbles easily, and with ink that smudges, building up a residue on the scanner that needs to be cleaned regularly.

About 300 sci-fi books have been scanned over the past two years. They’re usually only accessible on library computers (the material is IP-restricted due to copyright) but since Temple also uploaded them to HathiTrust Digital Library, they’ve been made available to read online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers who would like to study them as data can access them through the HathiTrust Research Center.

“The most important thing that we’re doing right now is reaching out to a series of other special collections and libraries to grow the digitization project,” Wermer-Colan said.

“This is going to be a very long-term project,” he said. “Fitting to a genre that thinks long-term.”