‘A continuous effort’:

How Temple’s COVID-19 testing program was built

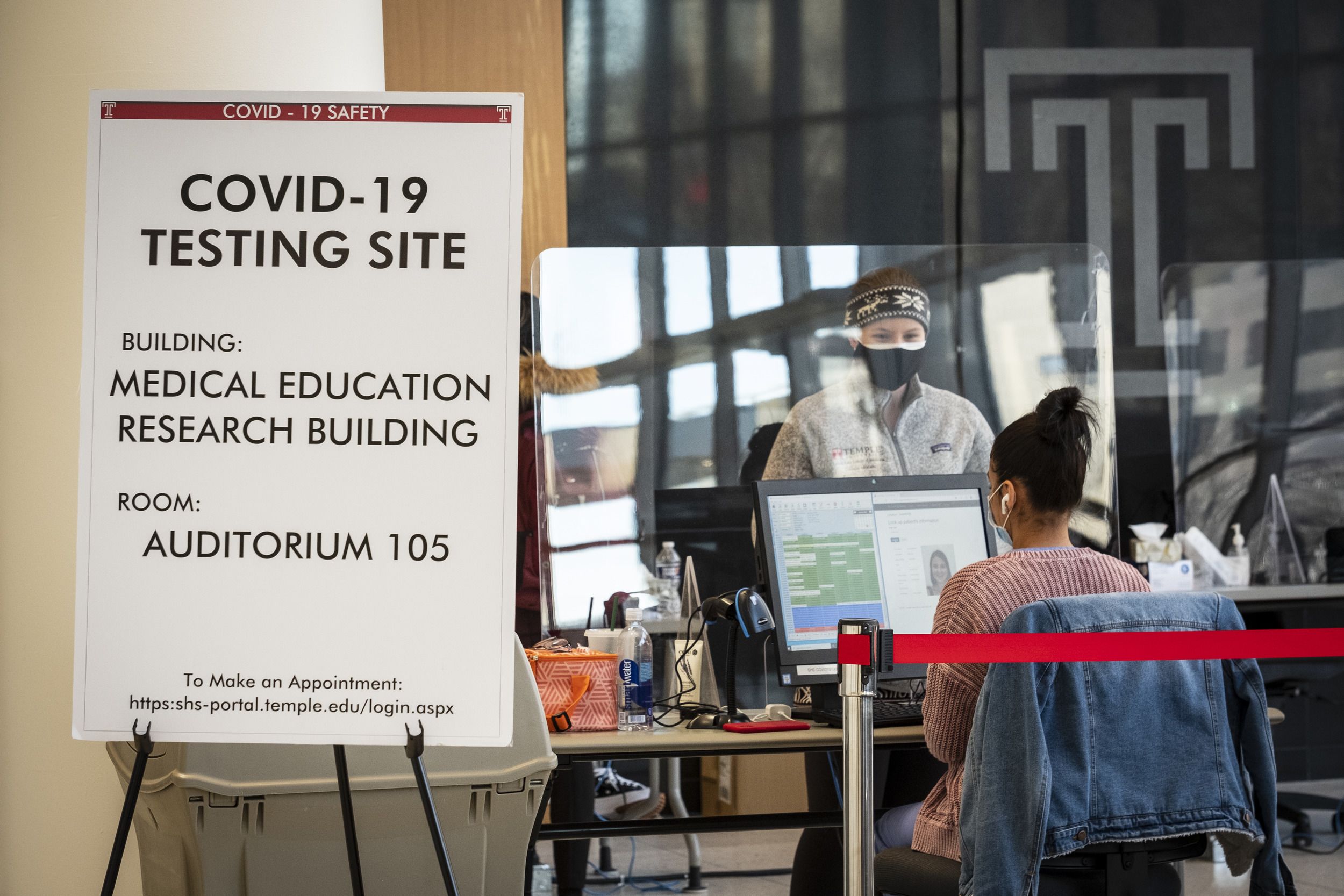

When the spring semester began in January, it was accompanied by the launch of Temple’s COVID-19 testing program: multiple testing sites, the university’s own specially developed testing kits and process, and a designated lab where tests would be screened.

The result of months of work, the program was a universitywide collaboration involving dozens of members of Temple’s community, from the Lewis Katz School of Medicine to Student and Employee Health Services and Information Technology Services.

Developing a testing protocol

The initial plan last March had been to use “off-the-shelf” test kits and technology made by Thermo Fisher Scientific, a leading science and technology firm. But COVID-19 testing materials were in such high demand that the company could not keep up.

“Many of the manufacturers of equipment had very specific reagents [supplies needed for the test] and test kits that were being used within that equipment,” said John Daly, dean of the Katz School of Medicine. “Consequently they had supply problems. An institution that was relying upon very specific equipment and very specific testing kits had difficulty in obtaining what it needed.”

Instead Temple began working with another biotechnology company, until a large shipment was delayed in Alaska for more than 10 days. The shipment thawed and the contents were ruined.

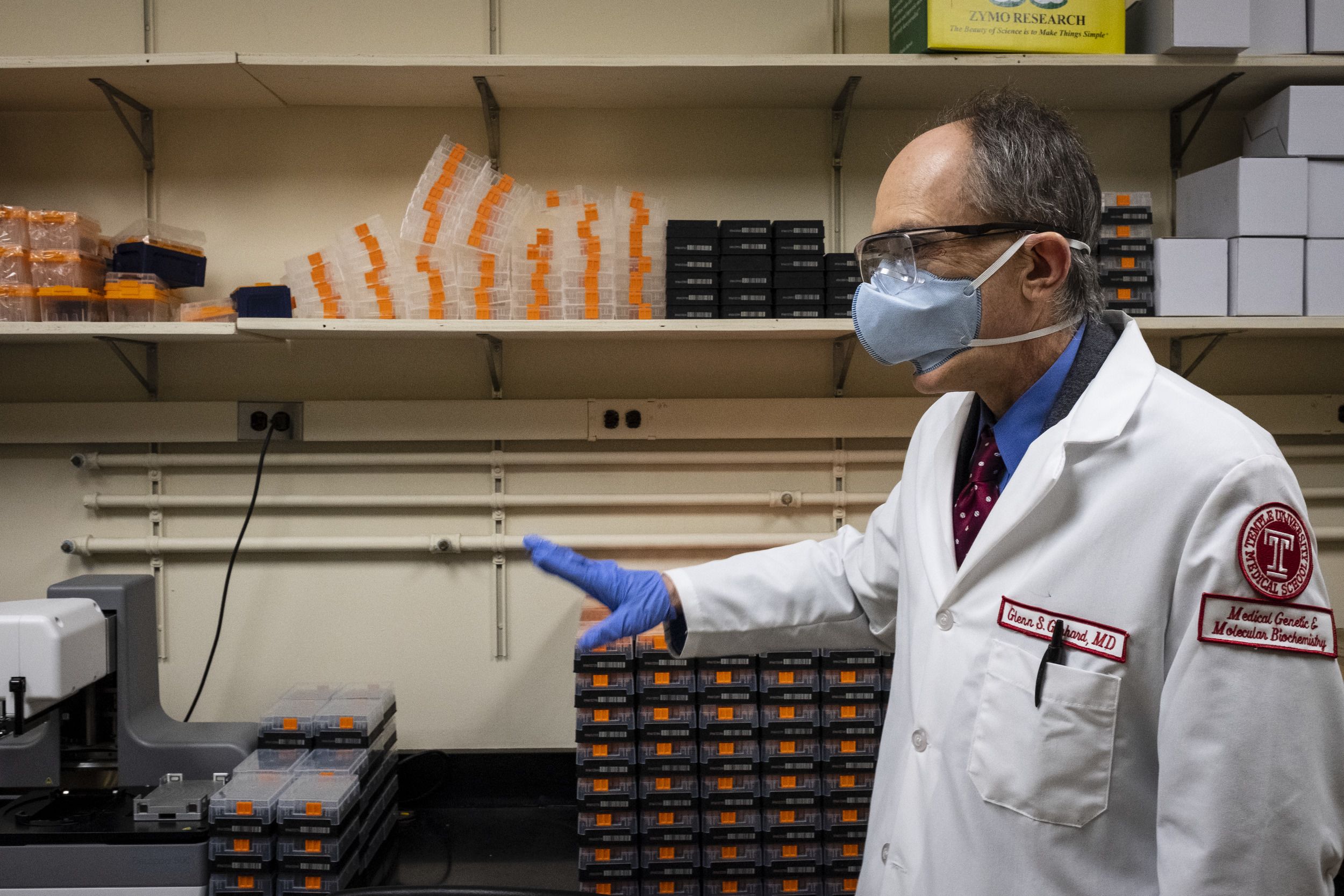

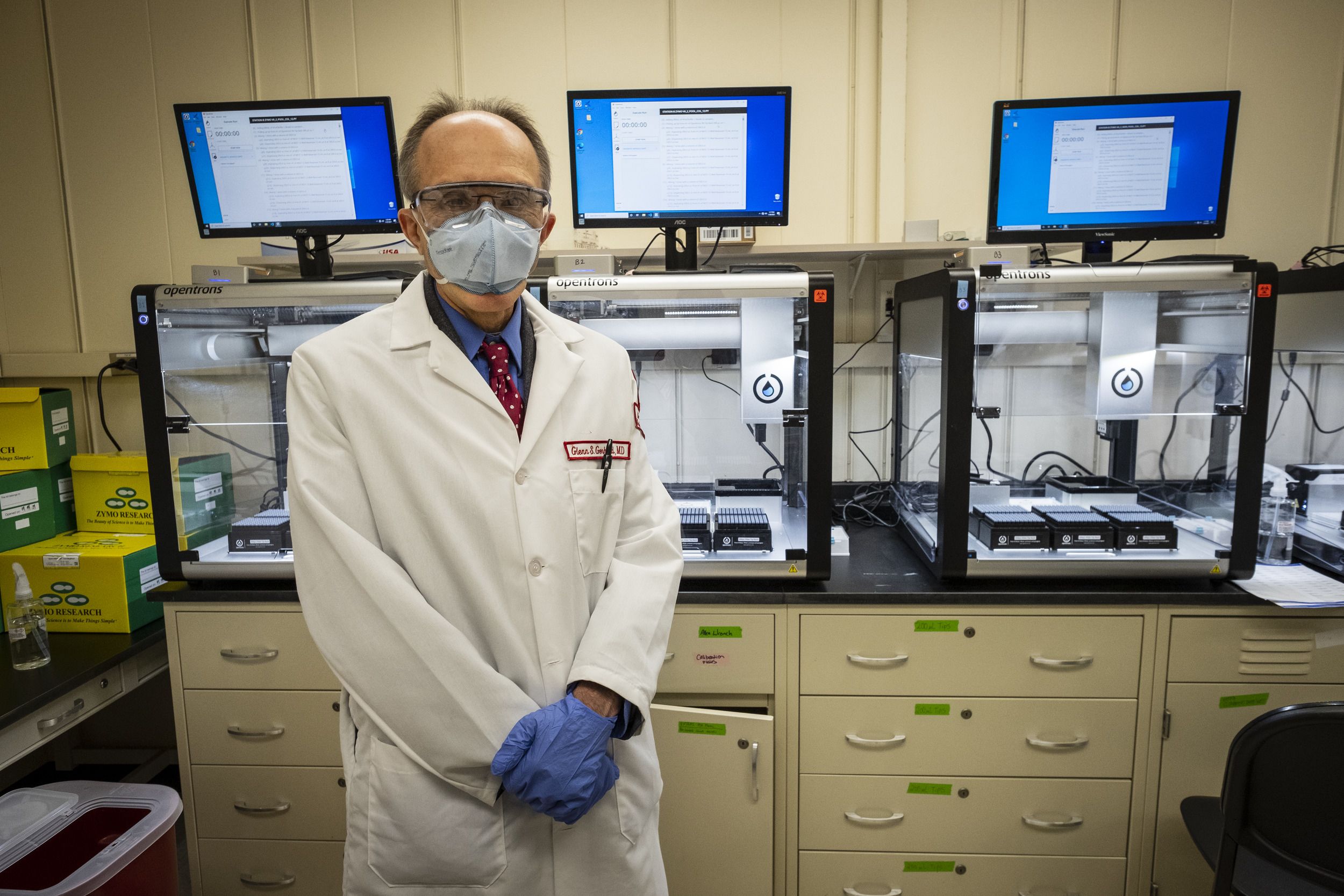

“That’s when we decided that we were going to develop an assay [the term used for the process of determining a COVID-19 test result] using off-the-shelf reagents ourselves,” said Glenn Gerhard, chair of the Department of Medical Genetics and Molecular Biochemistry at the Katz School of Medicine and head of the university’s COVID-19 testing lab. “Instead of buying a brand name test, you go generic and make your own. The sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been published and there’s several different assays around the world. So we used those as a guide to develop our own in-house protocol.”

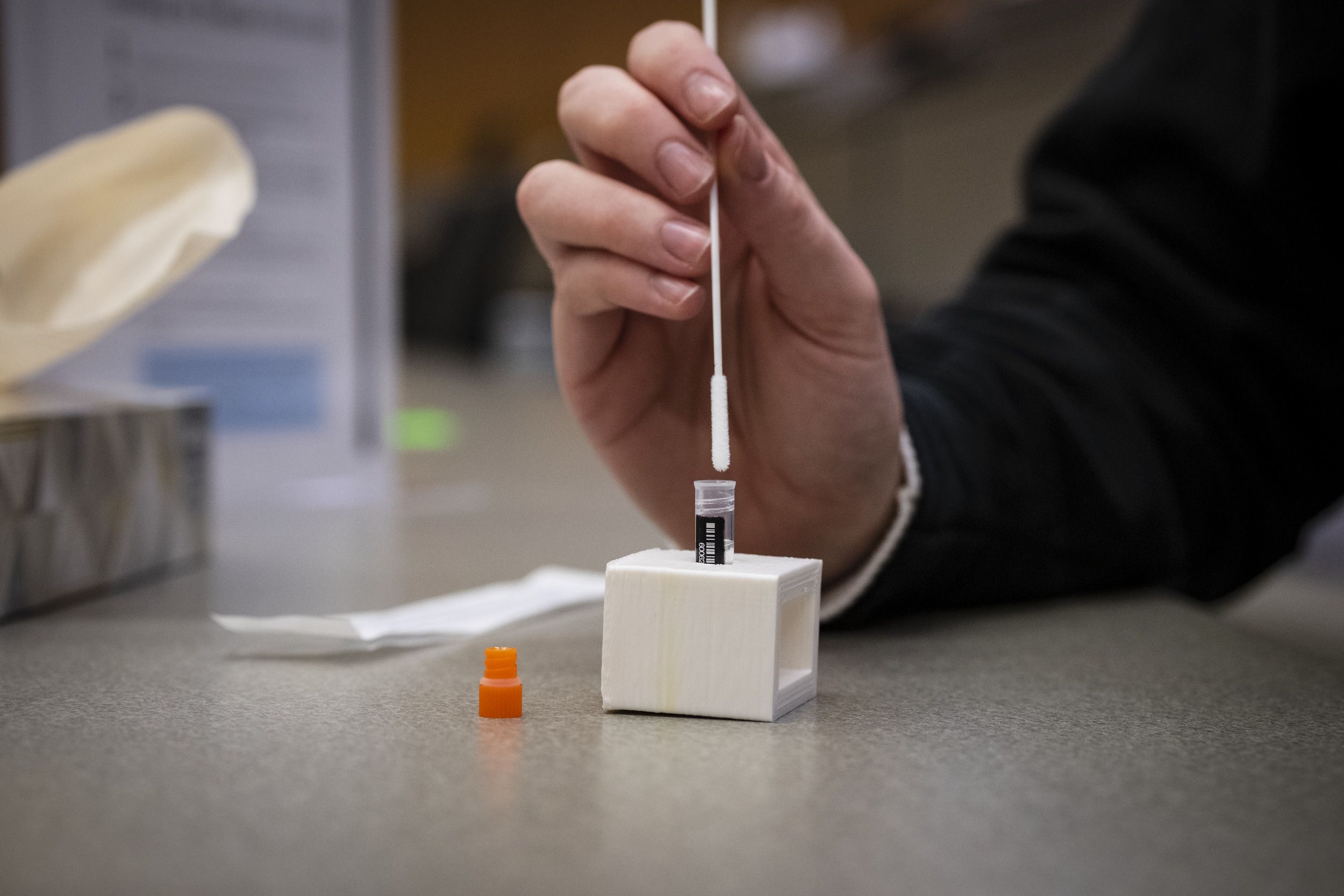

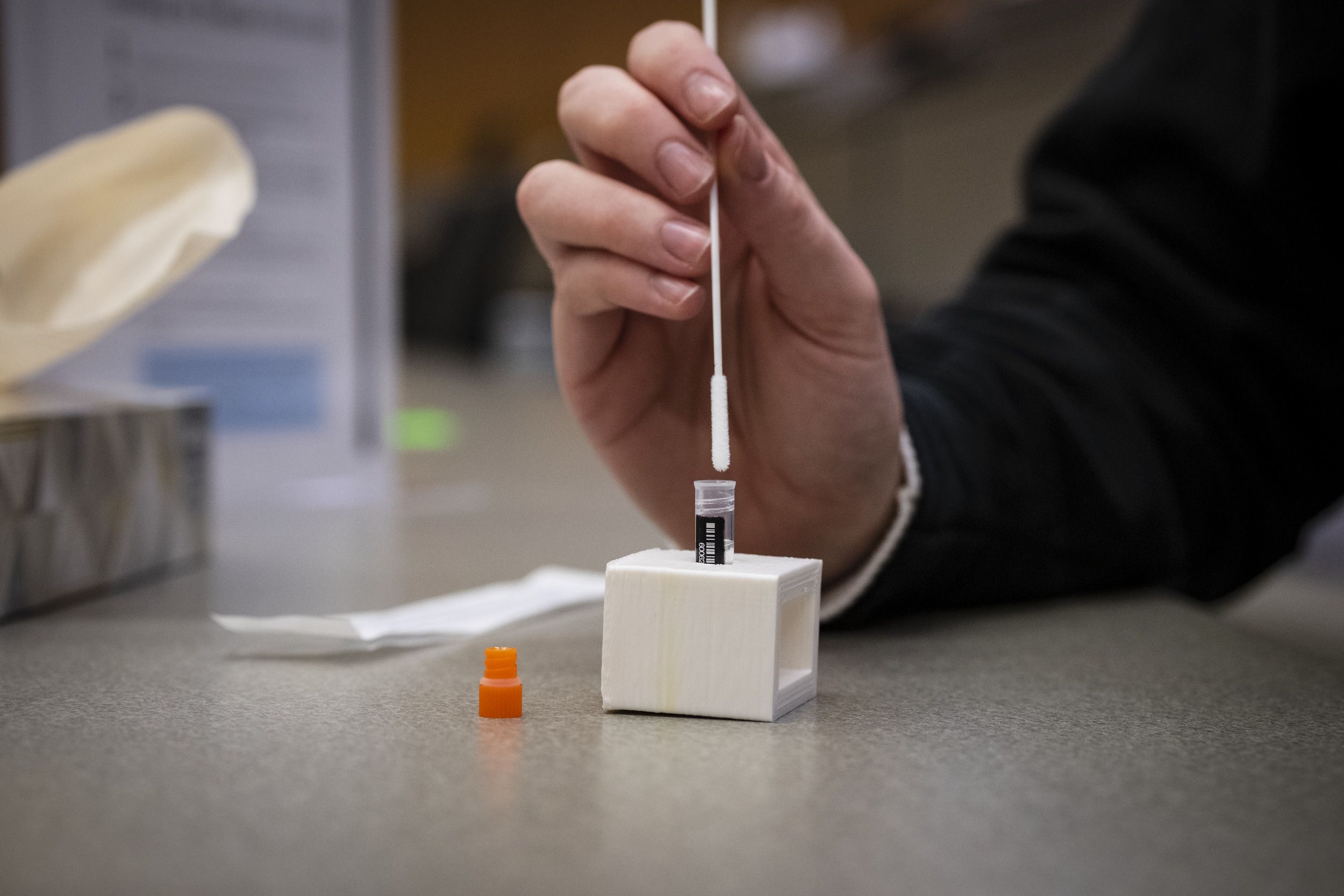

COVID-19 test samples are collected with swabs, which are then immersed in vials of fluid which kills the virus. “When you get the swab from your nose or mouth and it’s in the fluid, it comes to the lab. You then have to extract the virus RNA or protein,” Gerhard said, “out from the swab into the fluid and from the fluid into your own laboratory tube.” Temple’s testing process uses RNA—a nucleic acid that helps control the synthesis of proteins—because a small amount of it can be copied over and over again, making the most of what’s available in the sample.

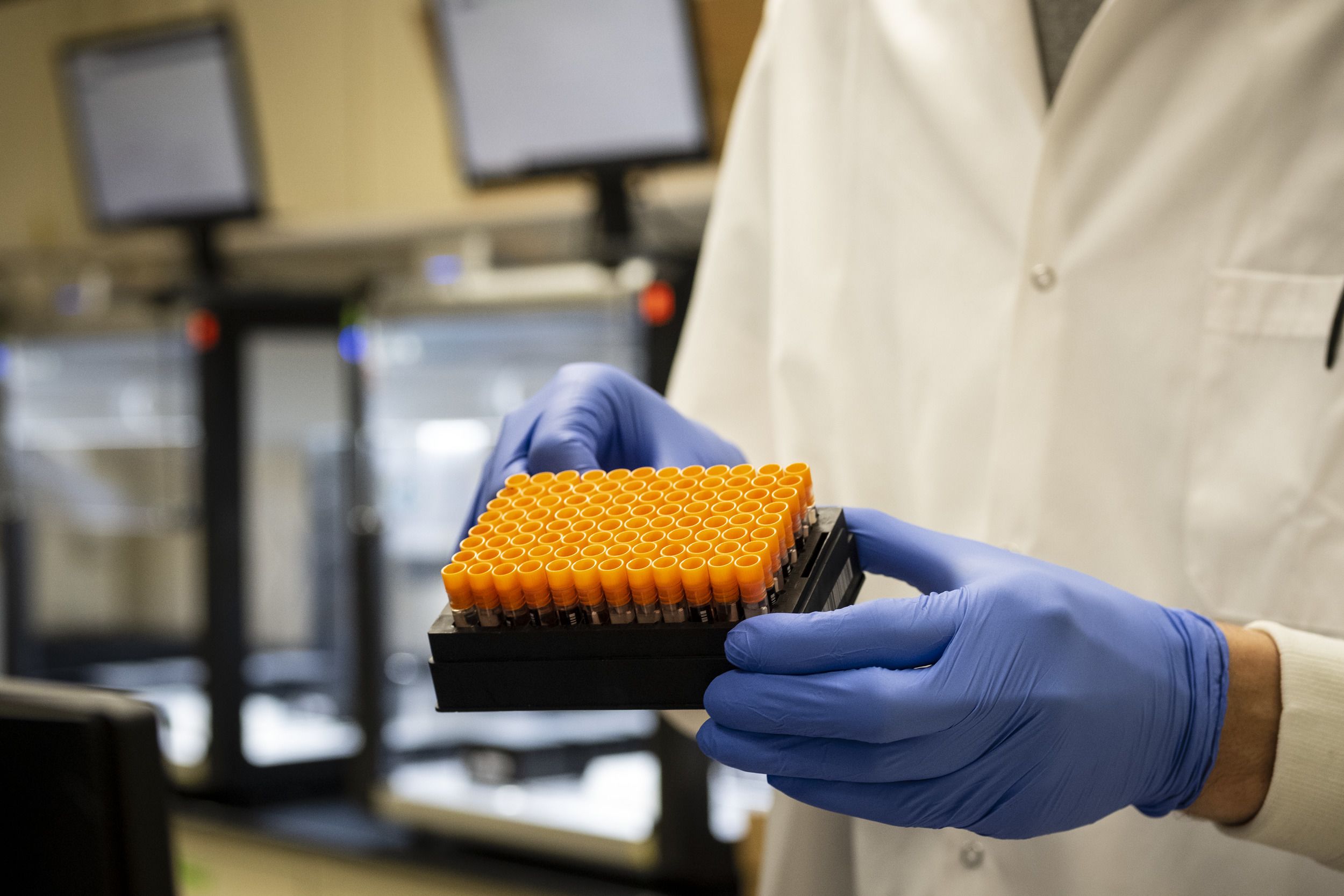

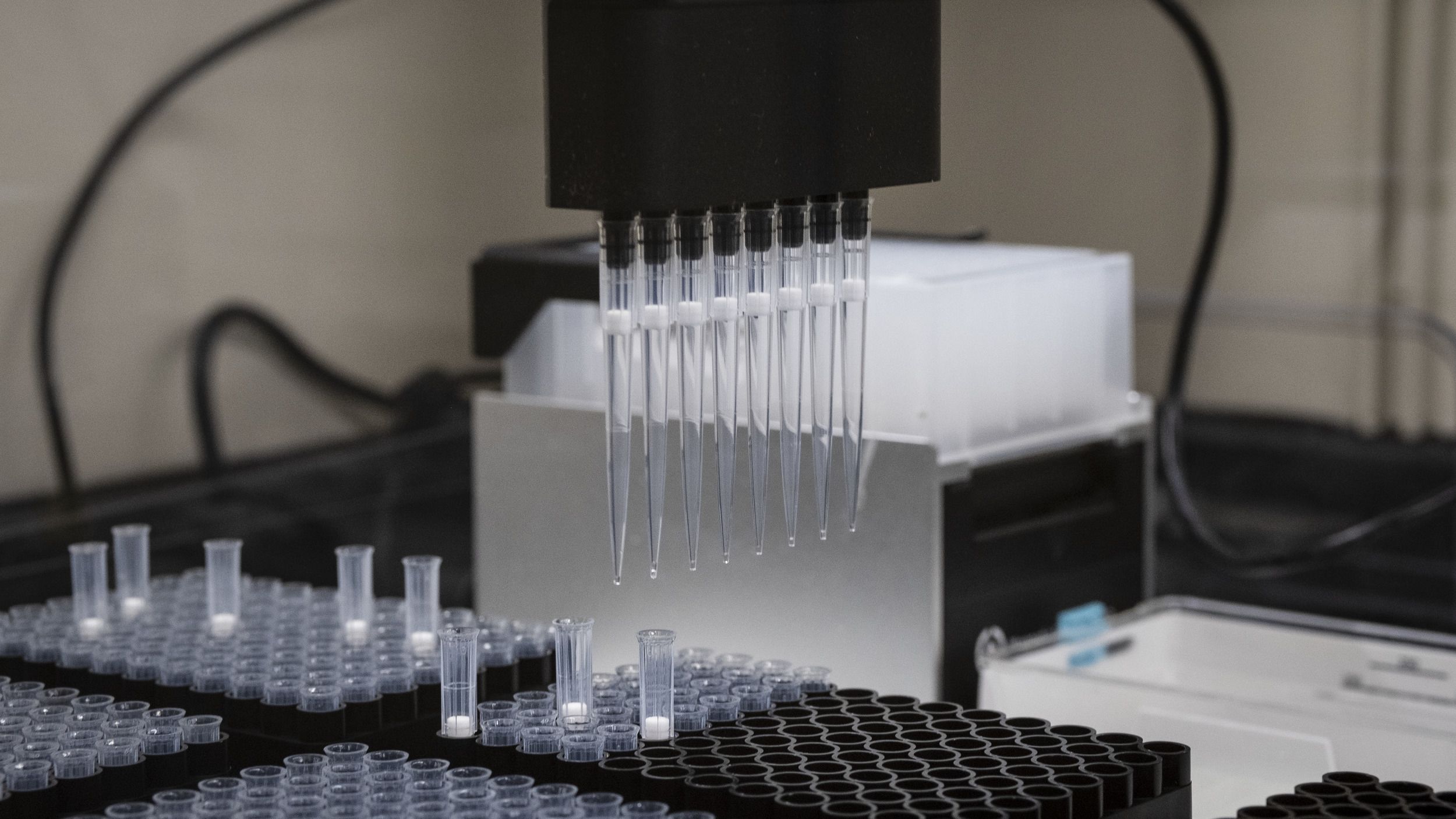

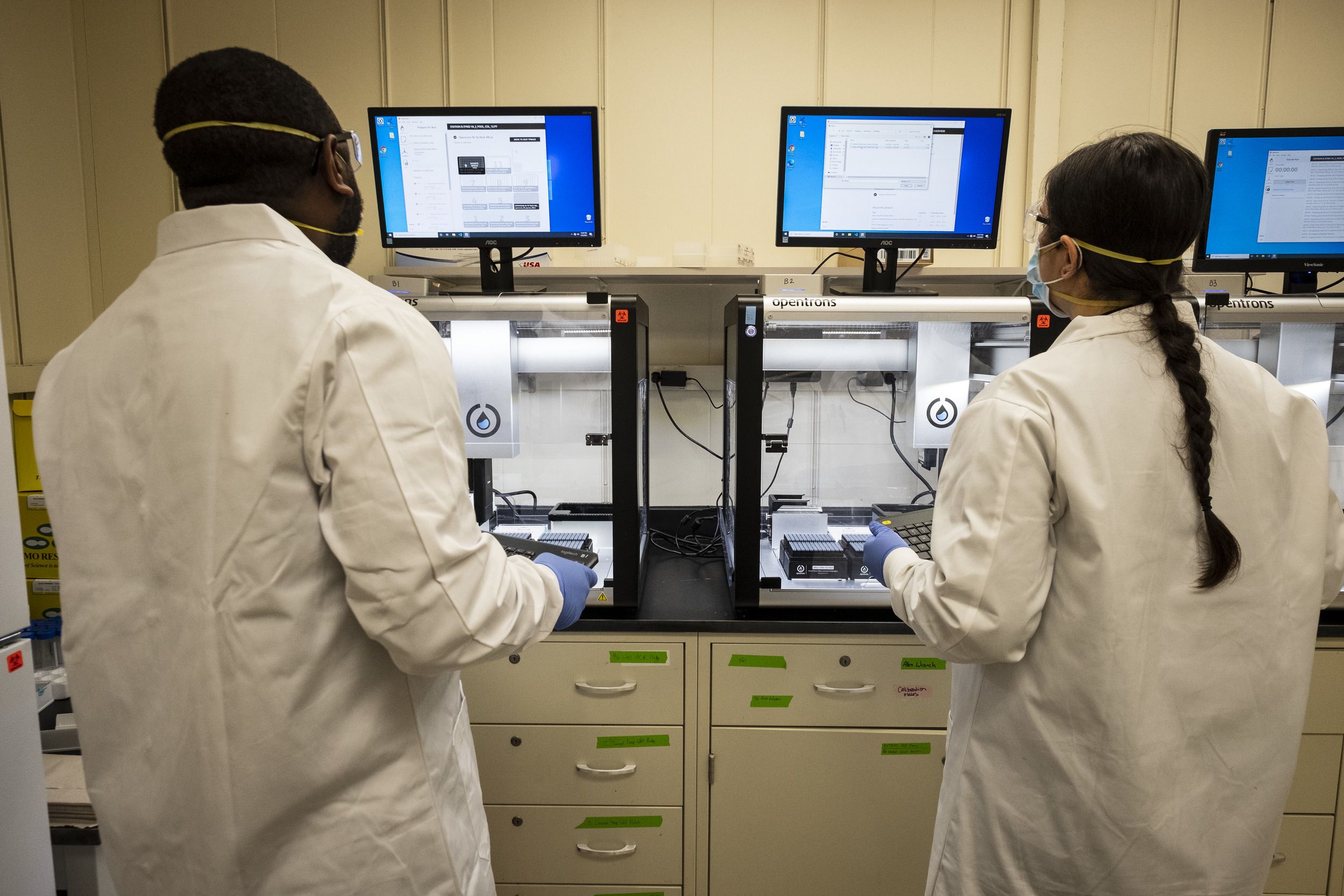

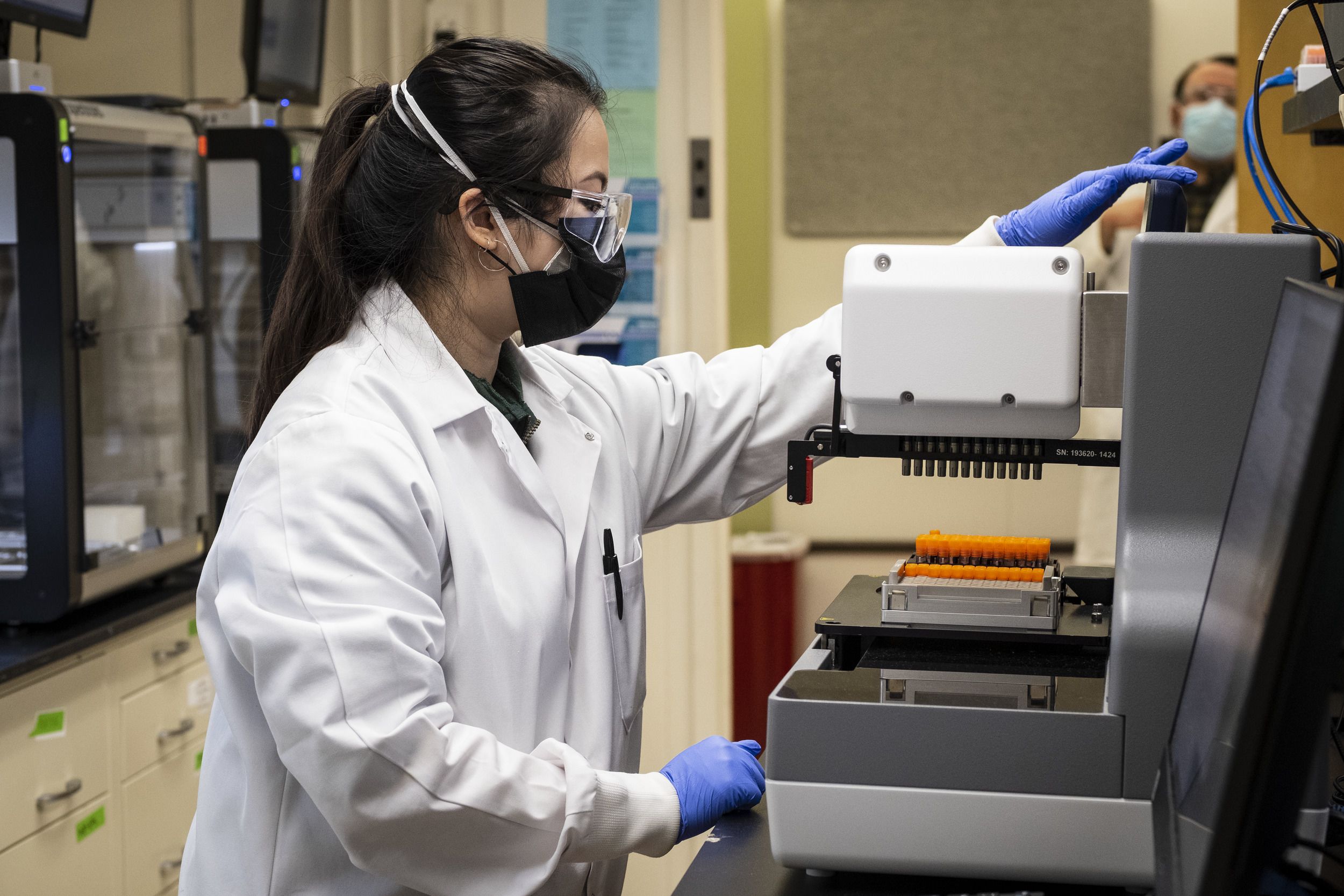

Stocks of the reagents Gerhard and his team needed were limited. In March, only two companies in the U.S. were making the plastic swabs necessary for test kits and they ran out, prompting Temple to switch to custom-designing and manufacturing the swabs in China. Test tubes were in high demand as well. Gerhard and his team sourced smaller tubes, figured out how to scale them for high-volume use and developed a workaround so they would mesh with the robots used in the lab.

“Our testing program is different,” Daly said. “It combines the use of equipment, reagents and supplies that are generic in nature and allows us to be able to purchase those supplies at a reduced cost, as well as to have better access, because they are generic.”

Implementing a branded, commercially available testing program similar to the one Temple developed would cost around $15 million, Gerhard said. Building a program in-house was a challenge, but it was also more cost-effective in the long run. “You have to do more and use your own ingenuity and work on it, but that still doesn’t come anywhere near the cost of what you pay when you buy off the shelf,” he said.

Setting up the testing sites

While Gerhard and his team created the testing kits and lab process, Mark Denys, senior director, health services and Meghan Duffy, an associate director in the office of the provost, worked on the testing sites. “We really looked to see where we needed the tests and what sites and locations would fit our needs, which was basically a large open space that could get people in and out very quickly and easily,” Denys said.

He and Duffy considered 20 different sites on the Health Sciences Center and Main Campus, discussing possible staffing and capacity, looking at the number of people who would be on campus and trying to predict the demand various locations would have to meet. Mitten Hall and the Howard Gittis Student Center were chosen because the former is often used for vaccinations and the latter is a familiar location for students. Also, both are easily accessible.

“It was a huge partnership with the ITS department, with facilities, with HR to get staff up and running, to get the spaces set up with power and data and equipment,” Duffy said. “It’s really been a universitywide initiative.”

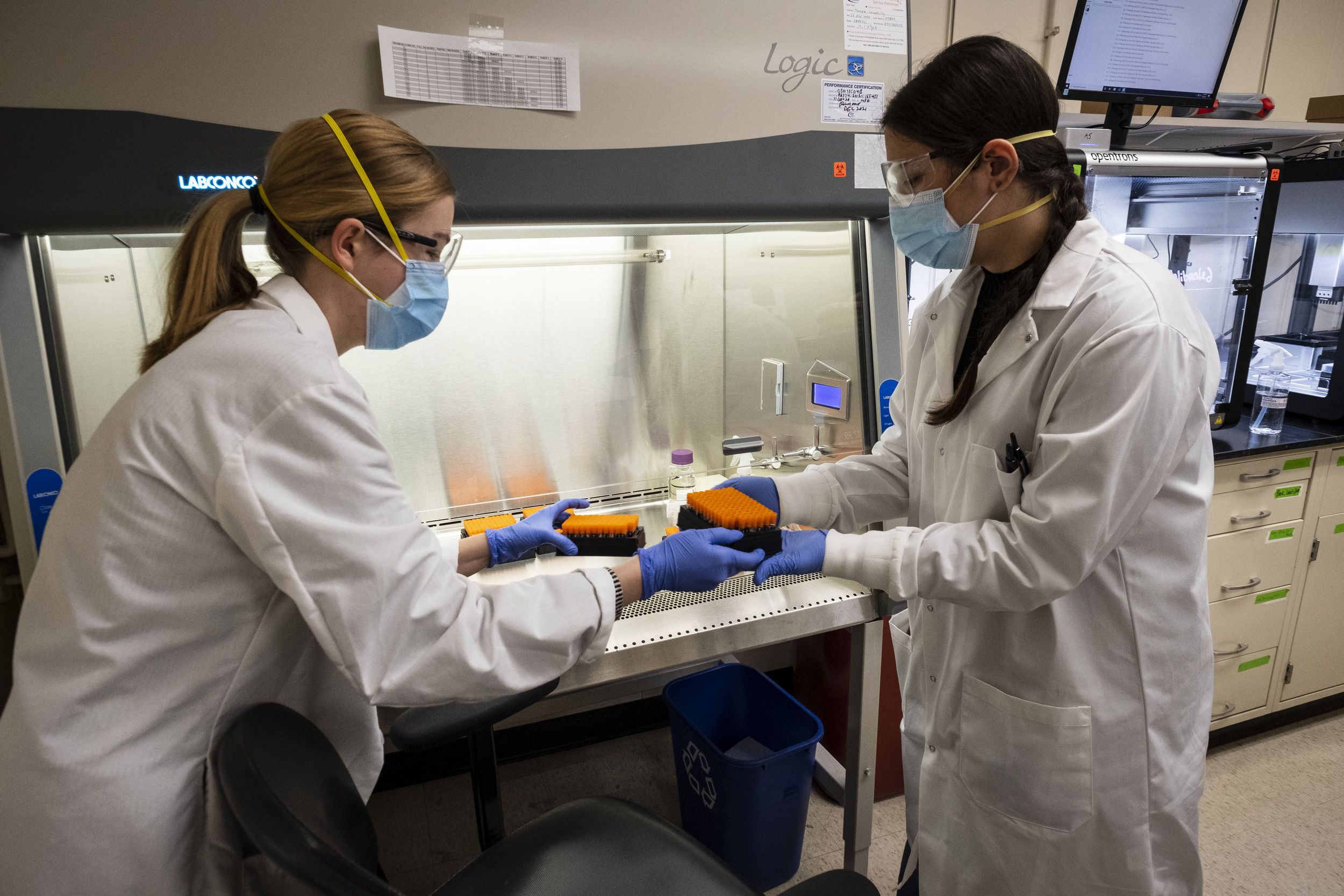

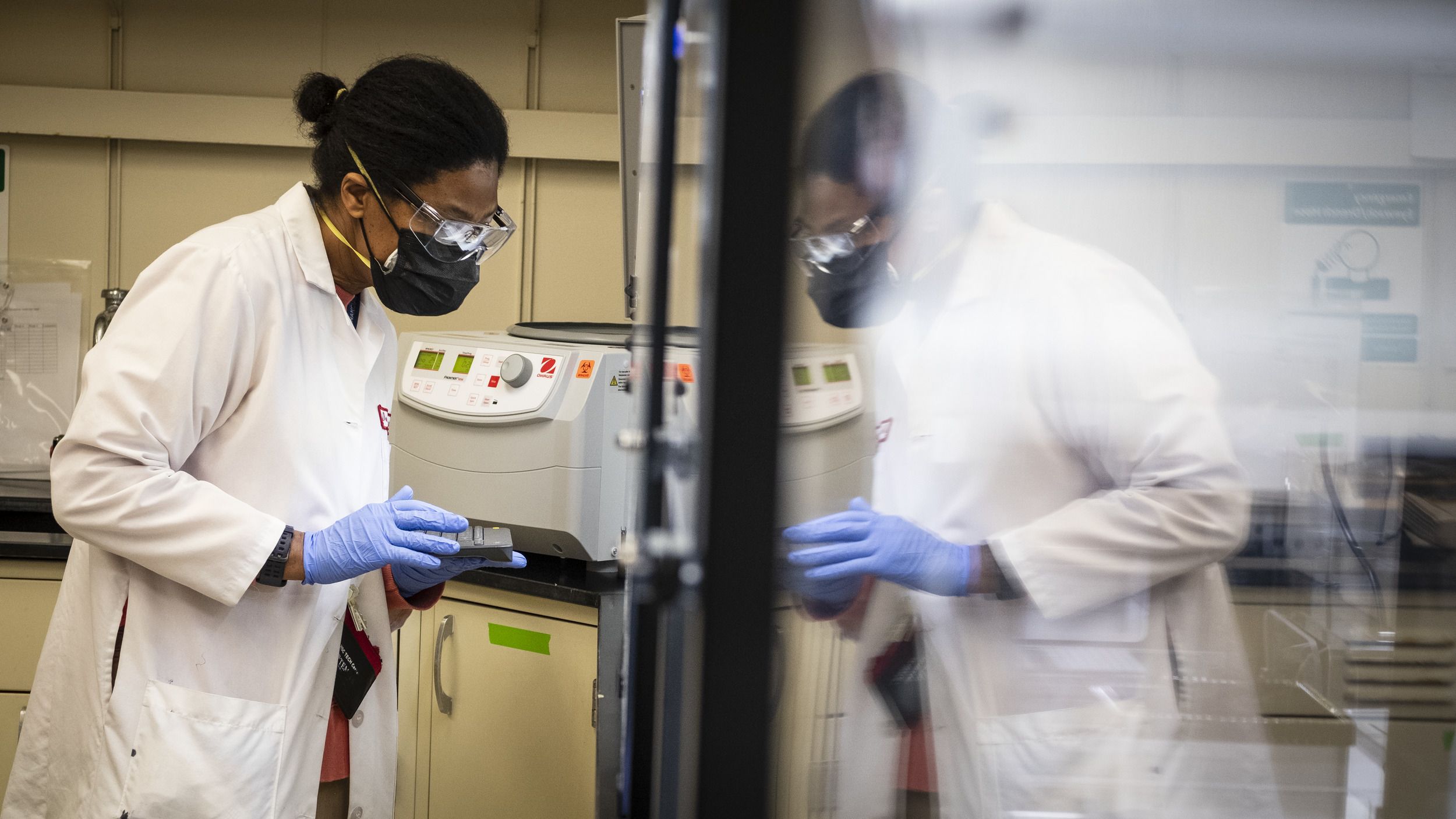

The biggest challenge they faced was the lack of time. Temple’s testing lab didn’t exist at Thanksgiving and had to be outfitted and staffed quickly, with Gerhard’s team expanding from three or four scientists and technicians to around a dozen. The testing sites also needed access to hard data because information covered by HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) can’t be transmitted using Wi-Fi.

Denys and Duffy worked through winter break, as did many of their colleagues, and hired 35 people in two weeks, some of whom were temporary employees that had to be replaced as they took up positions elsewhere.

“We had to train everybody in a very short period of time,” Denys said. “It’s a simple process that they can catch on to pretty quickly.”

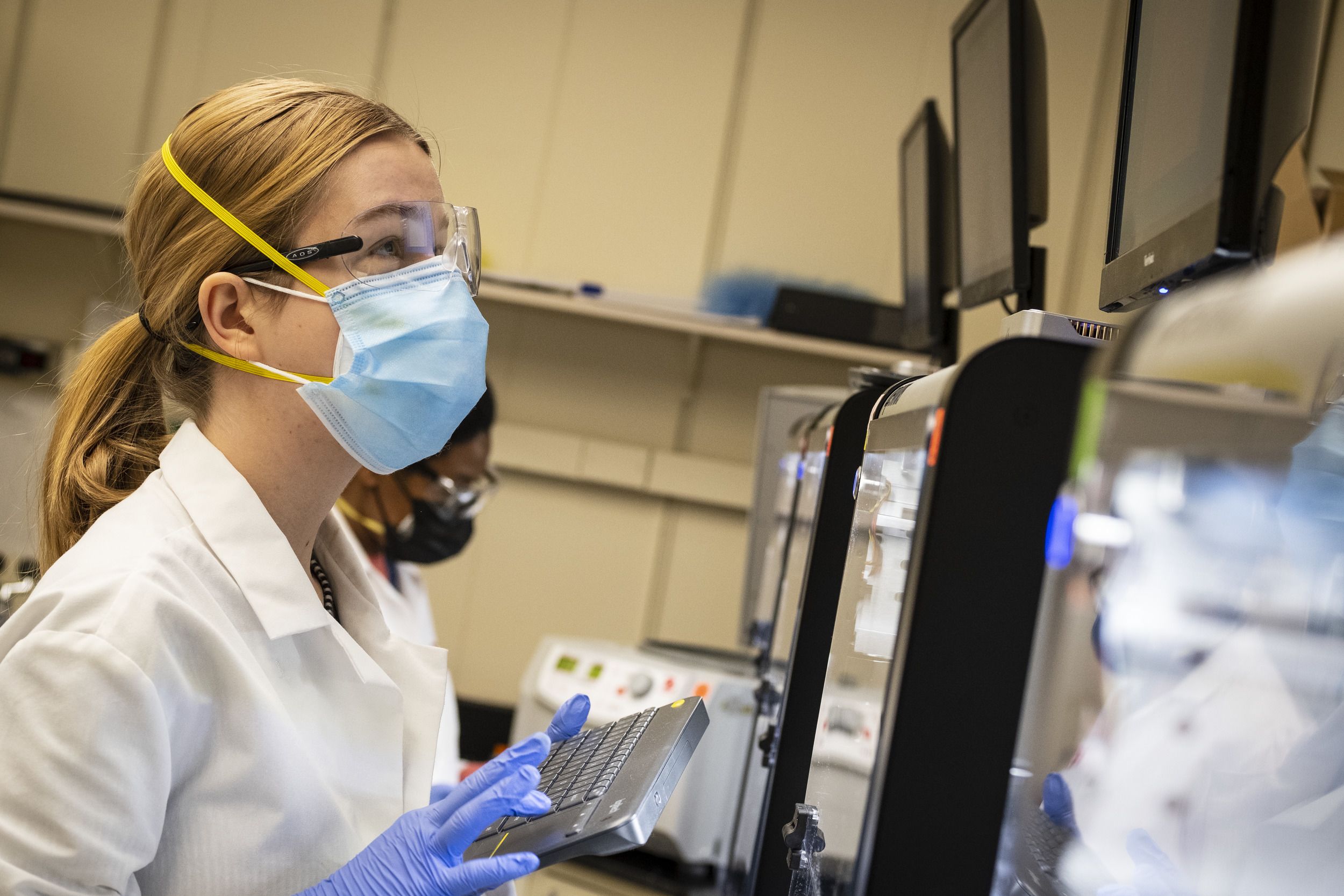

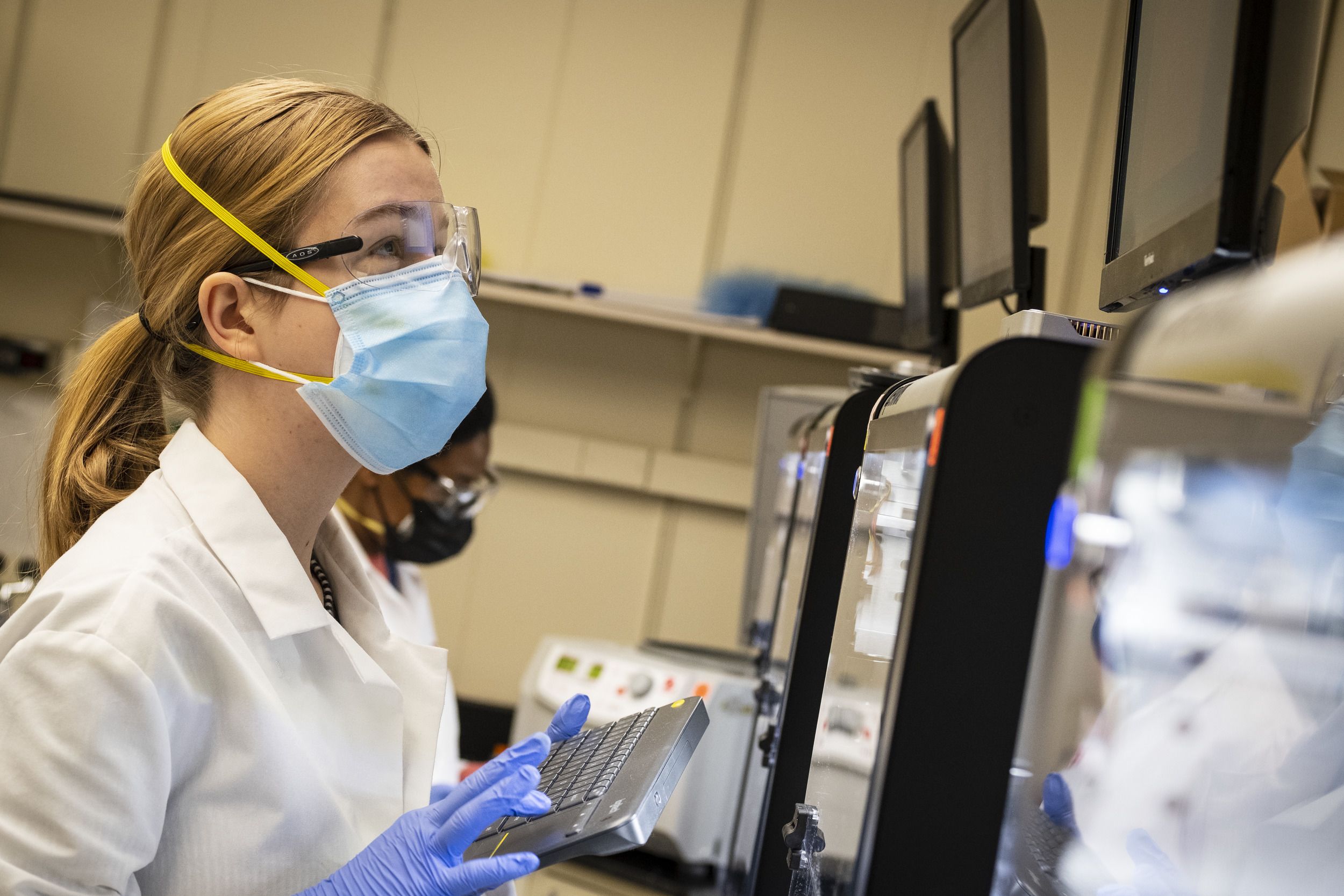

Another challenge was establishing the data flow between the testing sites, the lab and Student Health Services. “We already had an electronic medical record,” Denys said. “But we have to get a person’s unique identification to the lab along with a lab order. Then, they have to be able to link the test vial up to the individual, get the result and make sure that it’s assigned to that individual. It all has to be ironclad.” Student Health receives a copy of the results, which they then share with students.

“By testing this often and this many groups, the goal is to prevent or limit the chances of that positive individual causing a cluster of individuals or a cluster causing an outbreak.”

How the testing process works

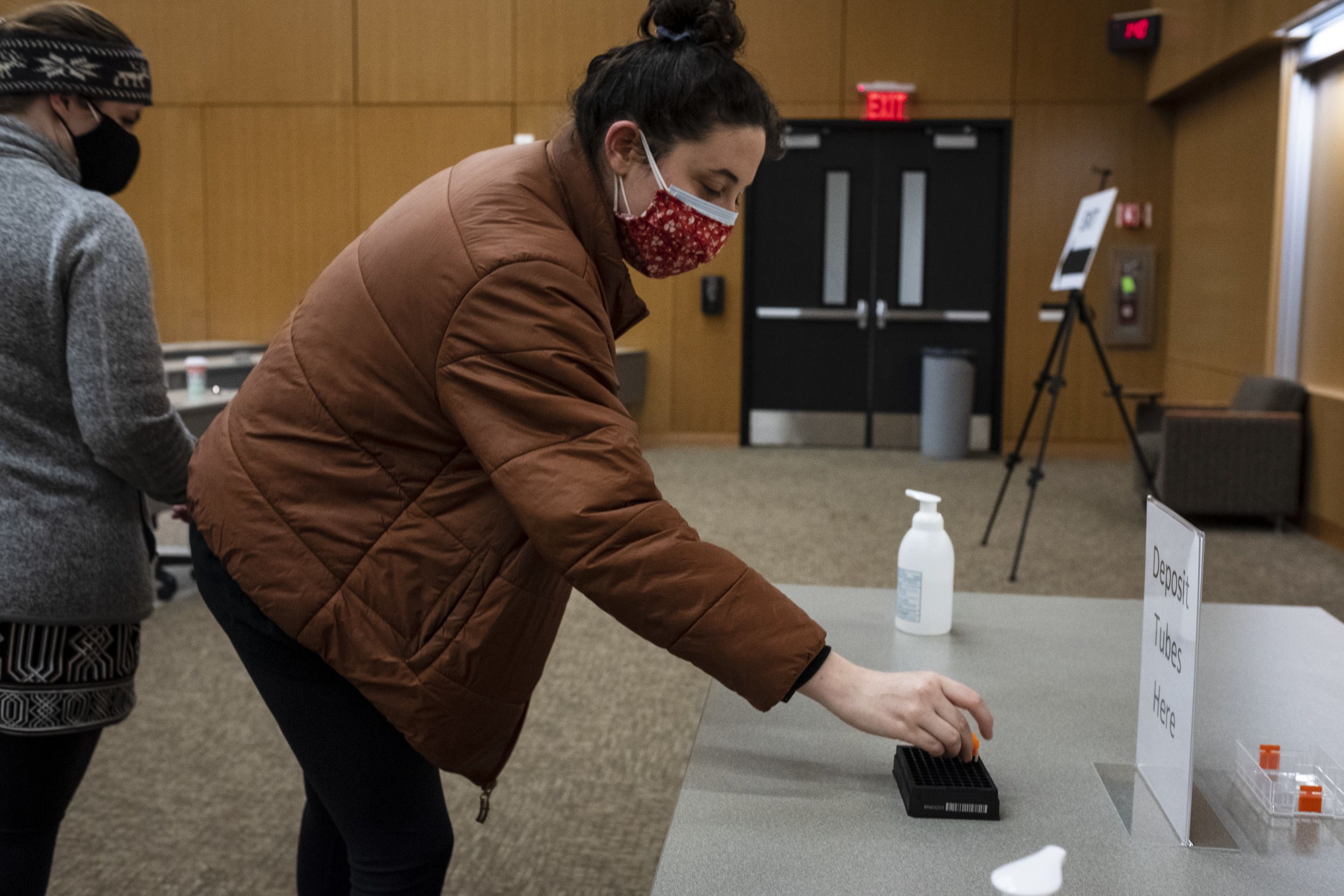

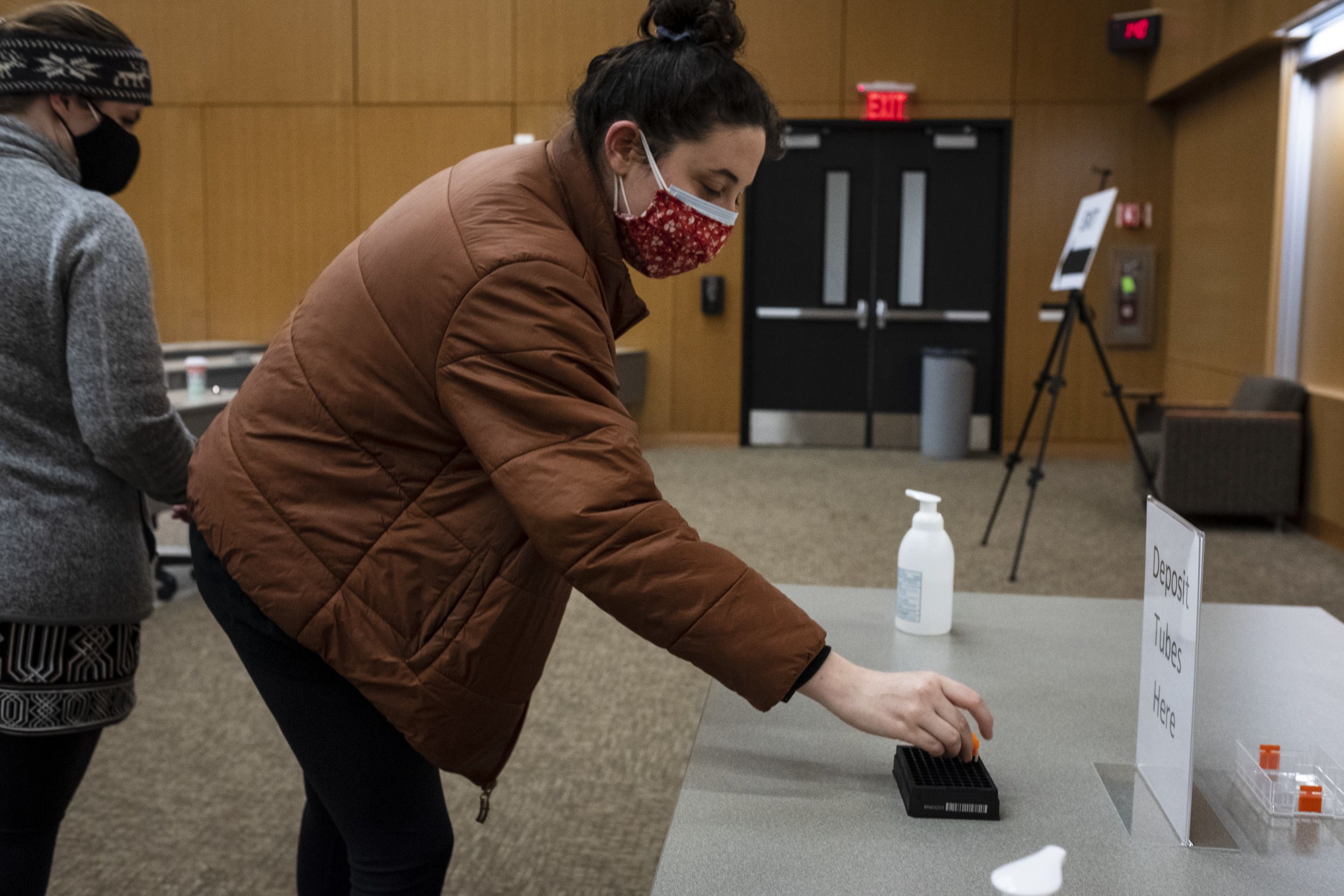

Testing schedules vary according to different categories, based on where students live and how many in-person classes they take. The testing process begins when a student checks in at a testing site and receives a vial with a barcode that’s entered into Temple’s system. Each test is self-administered under observation, to ensure it’s done correctly.

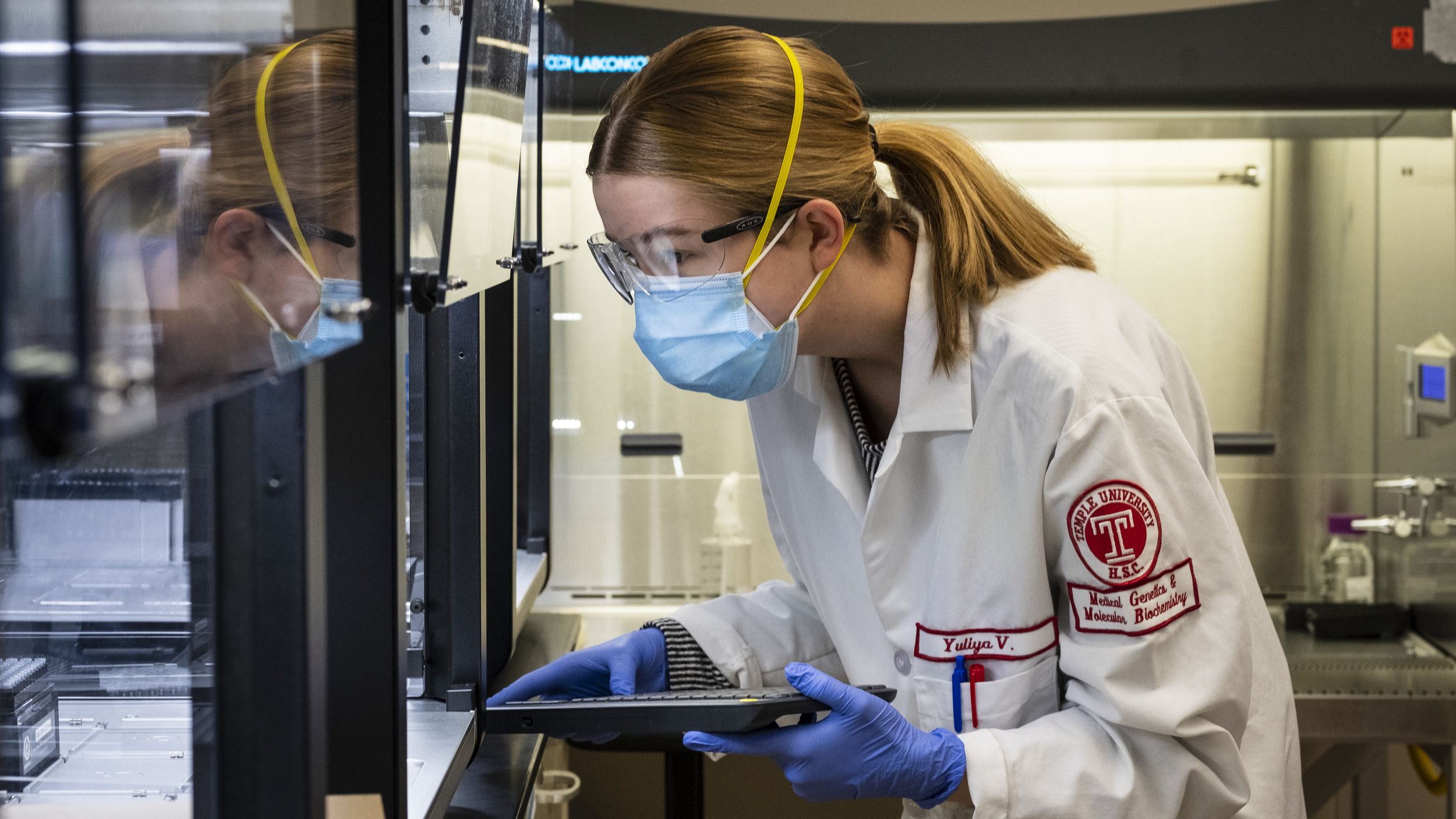

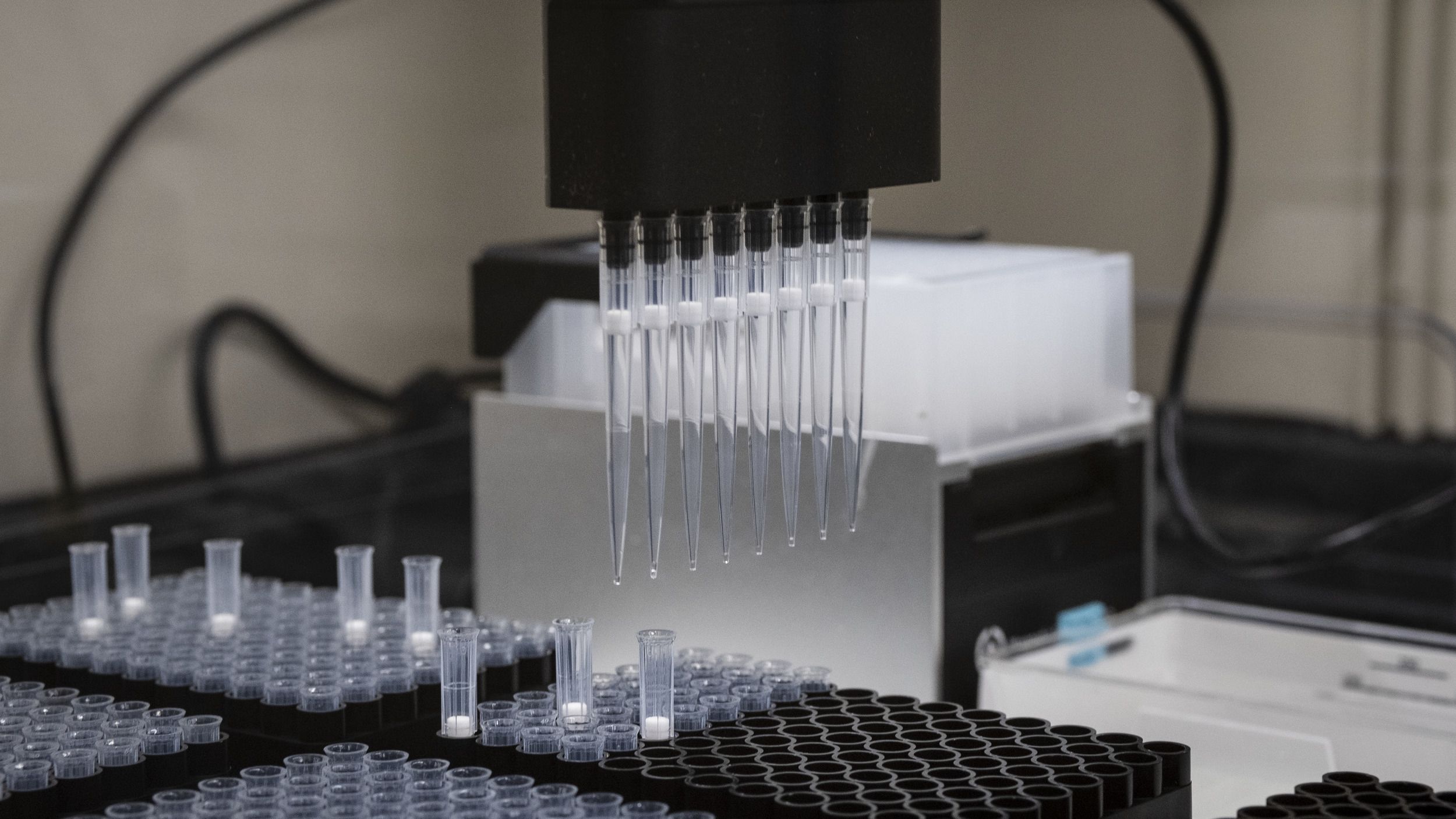

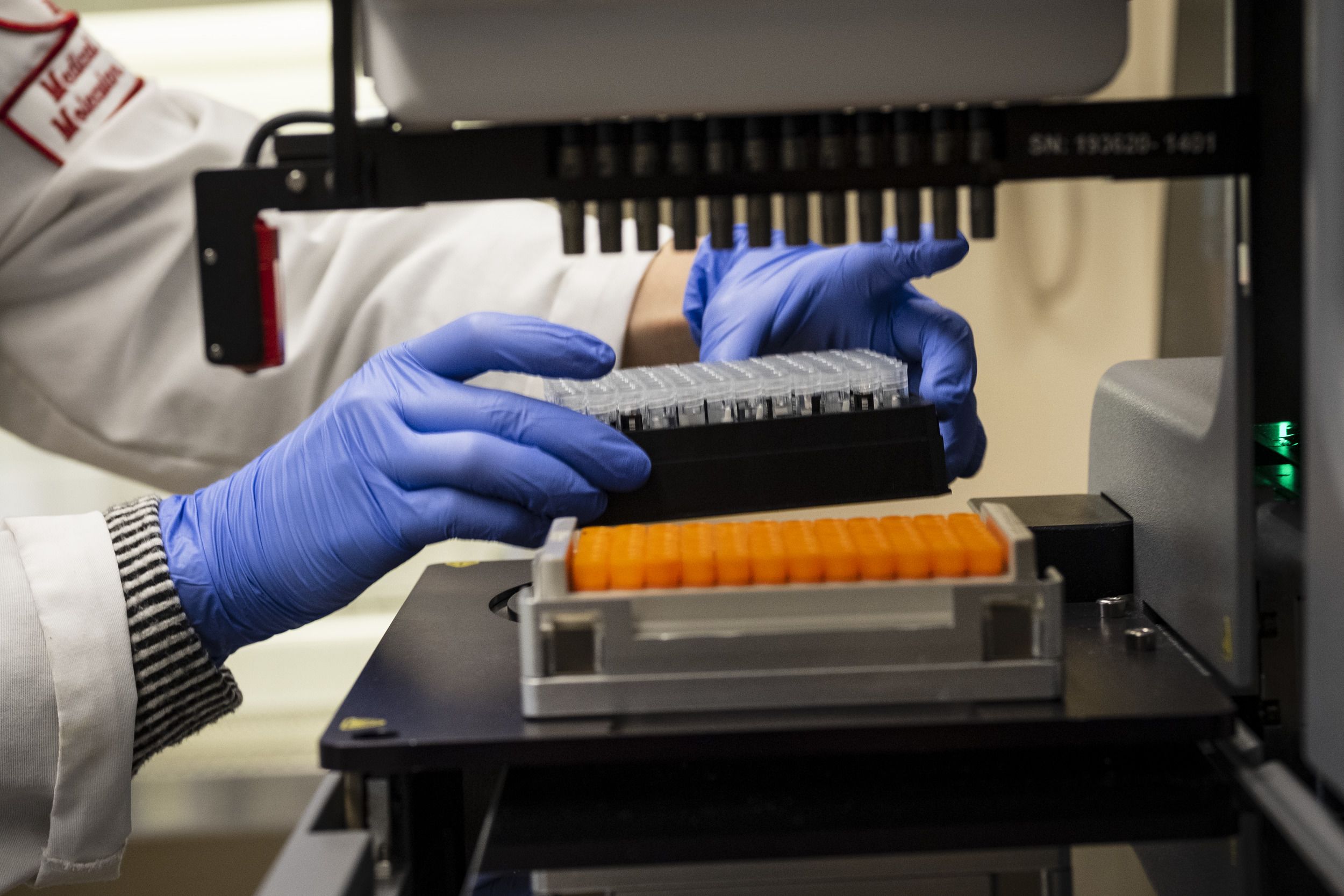

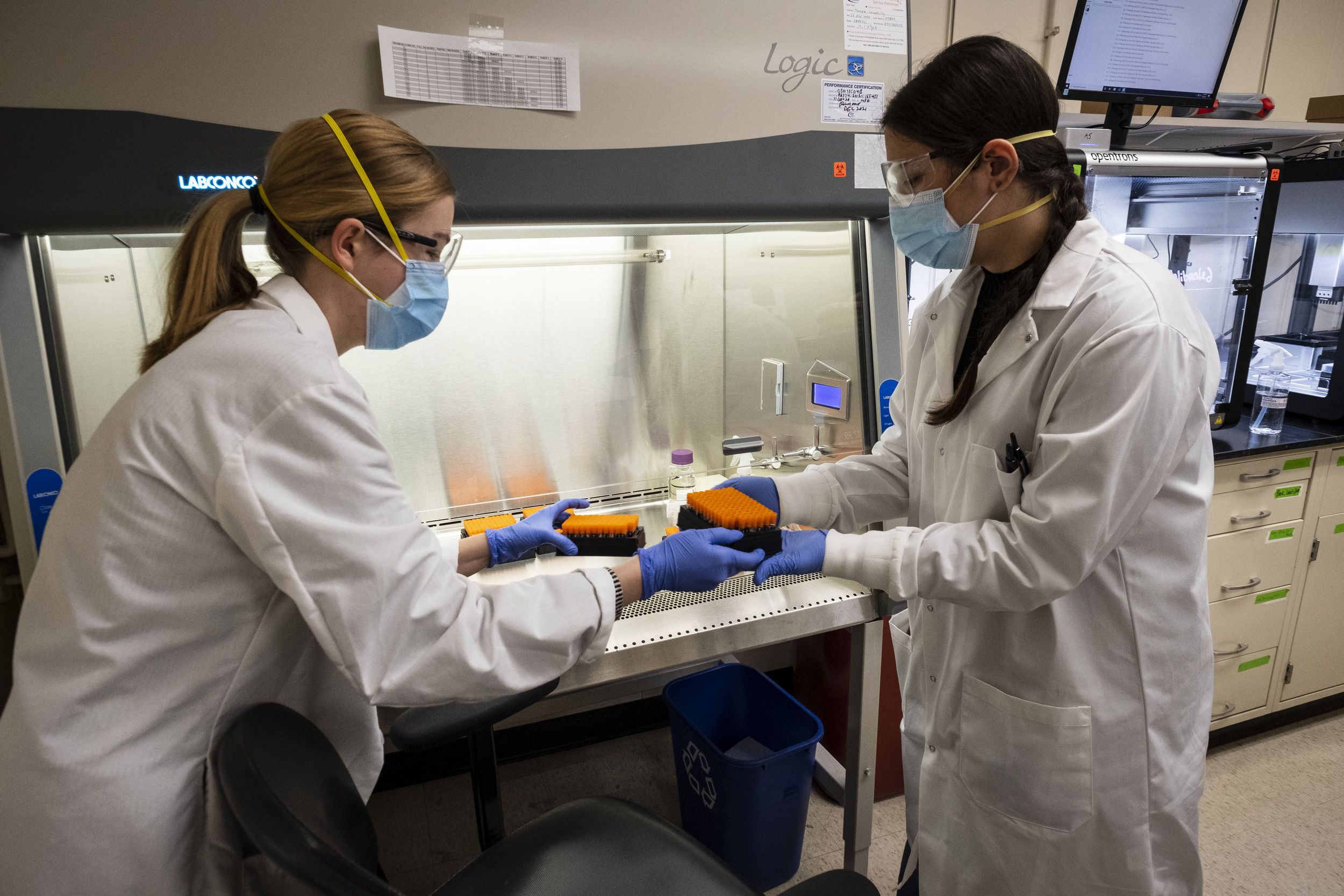

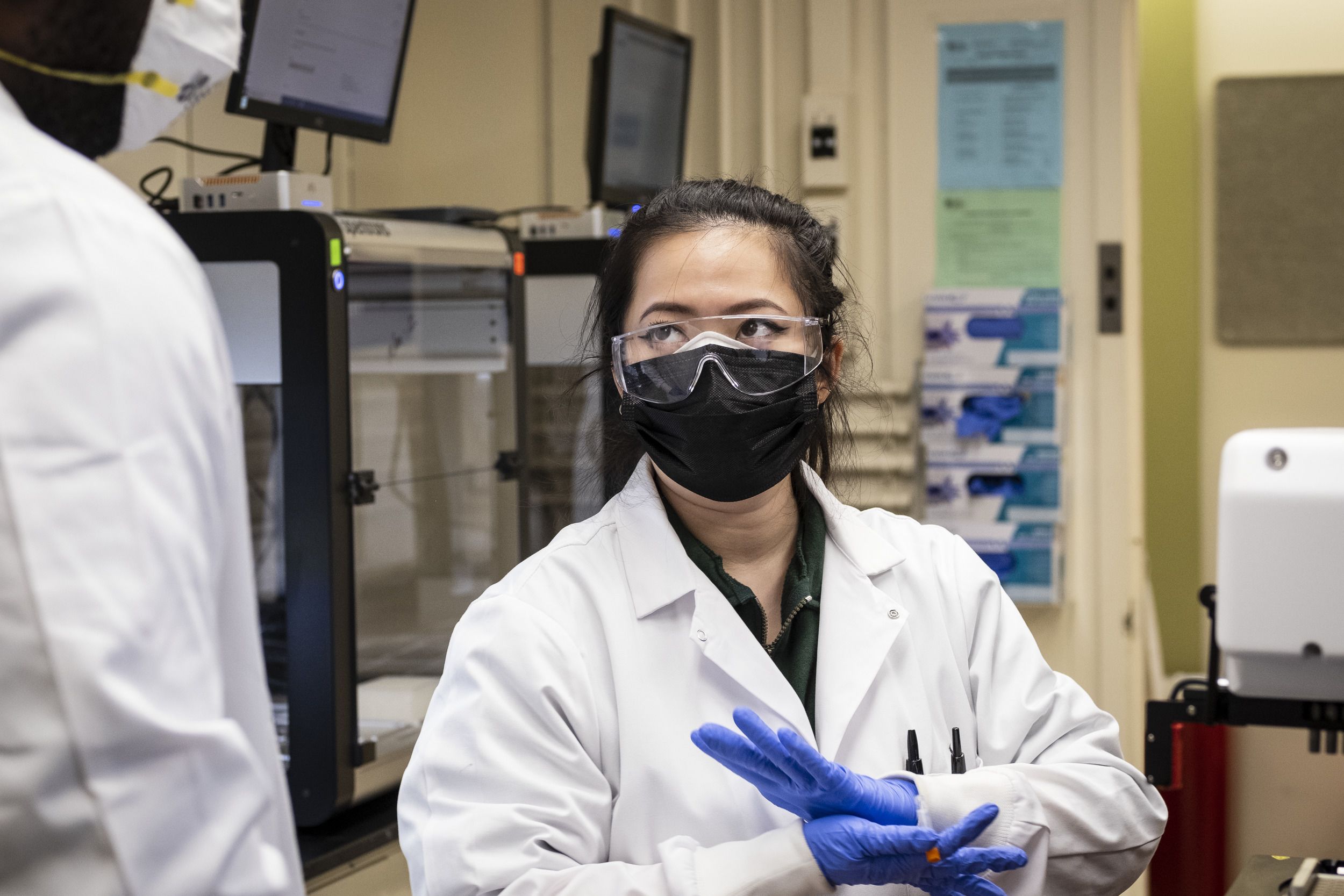

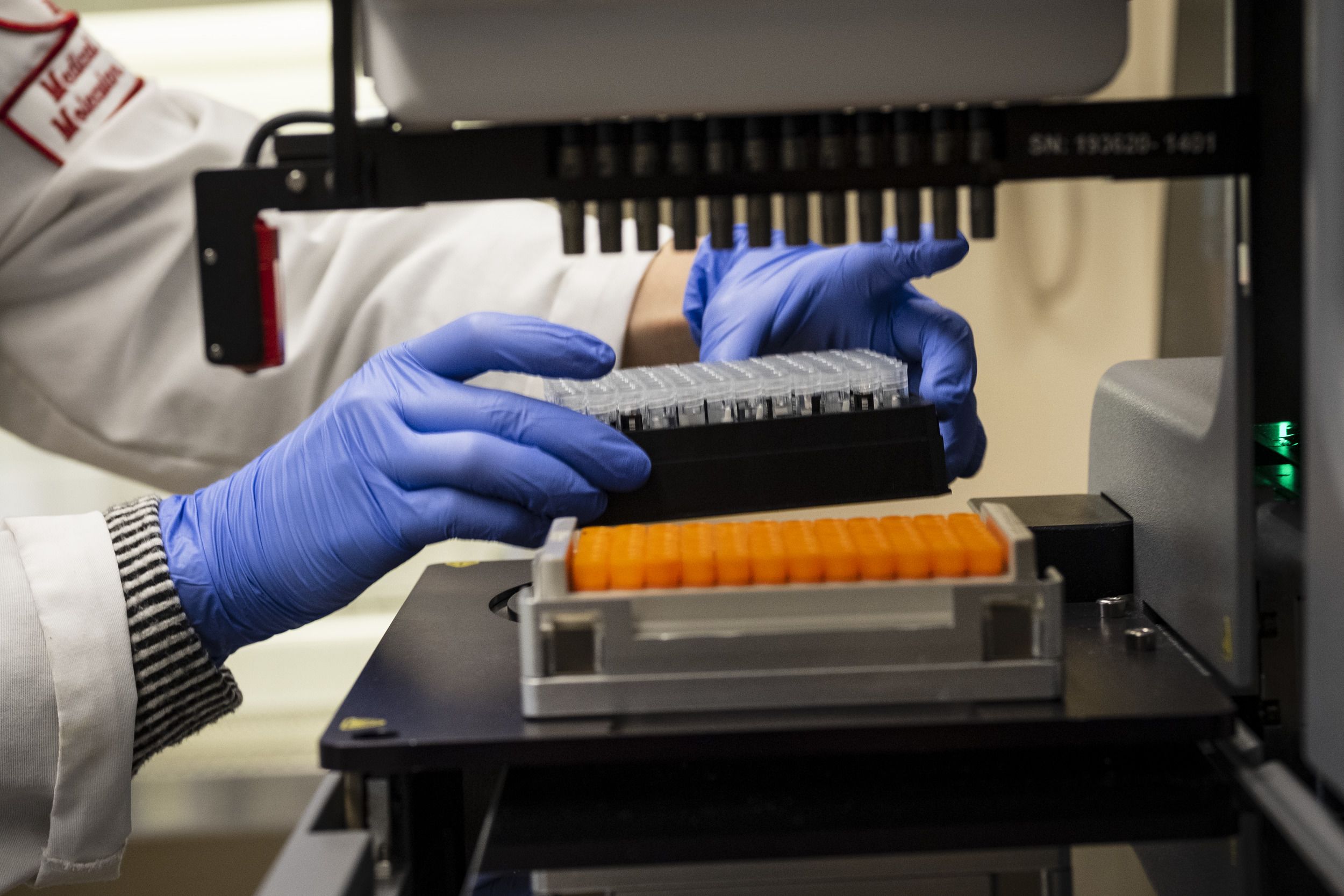

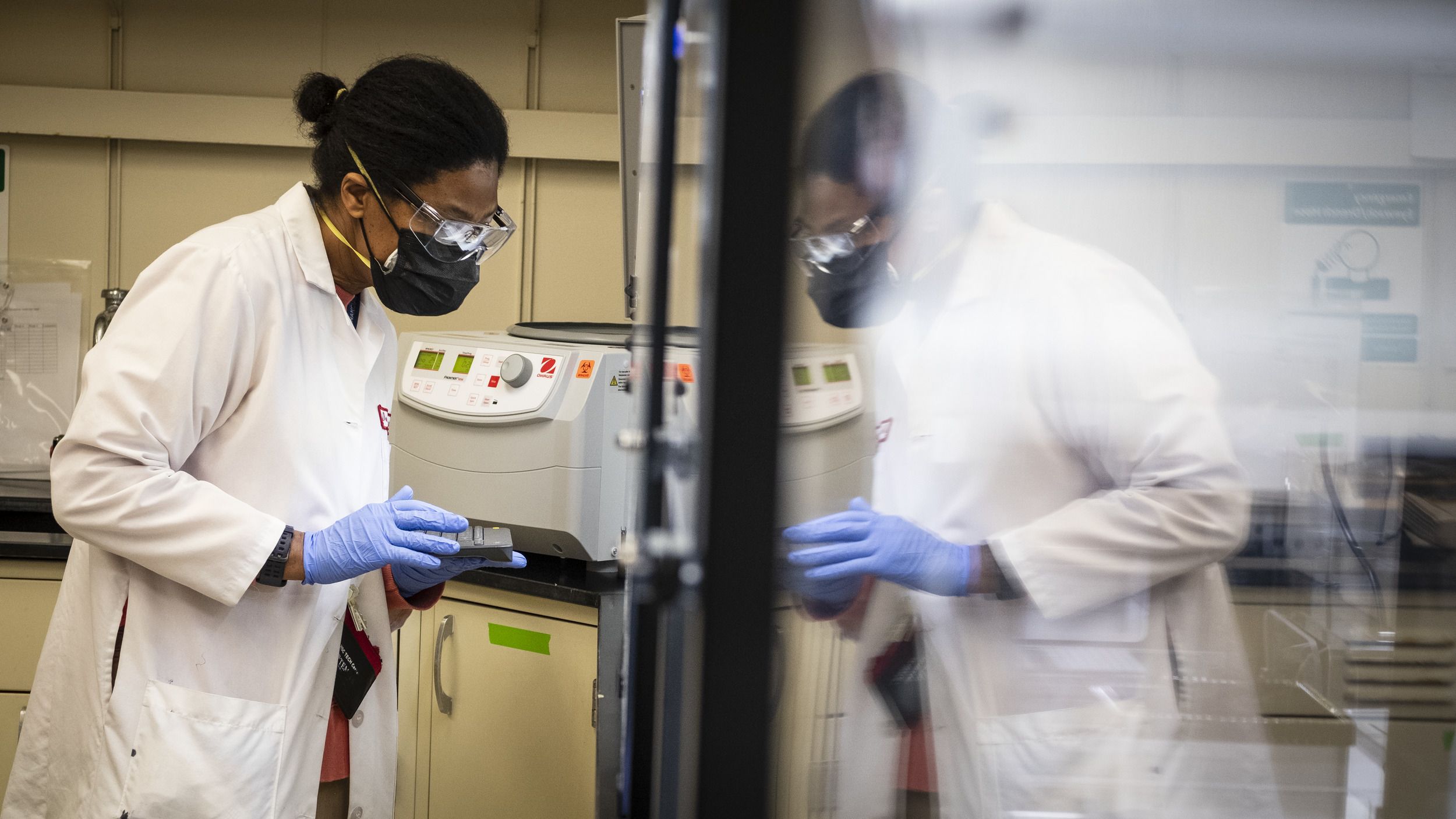

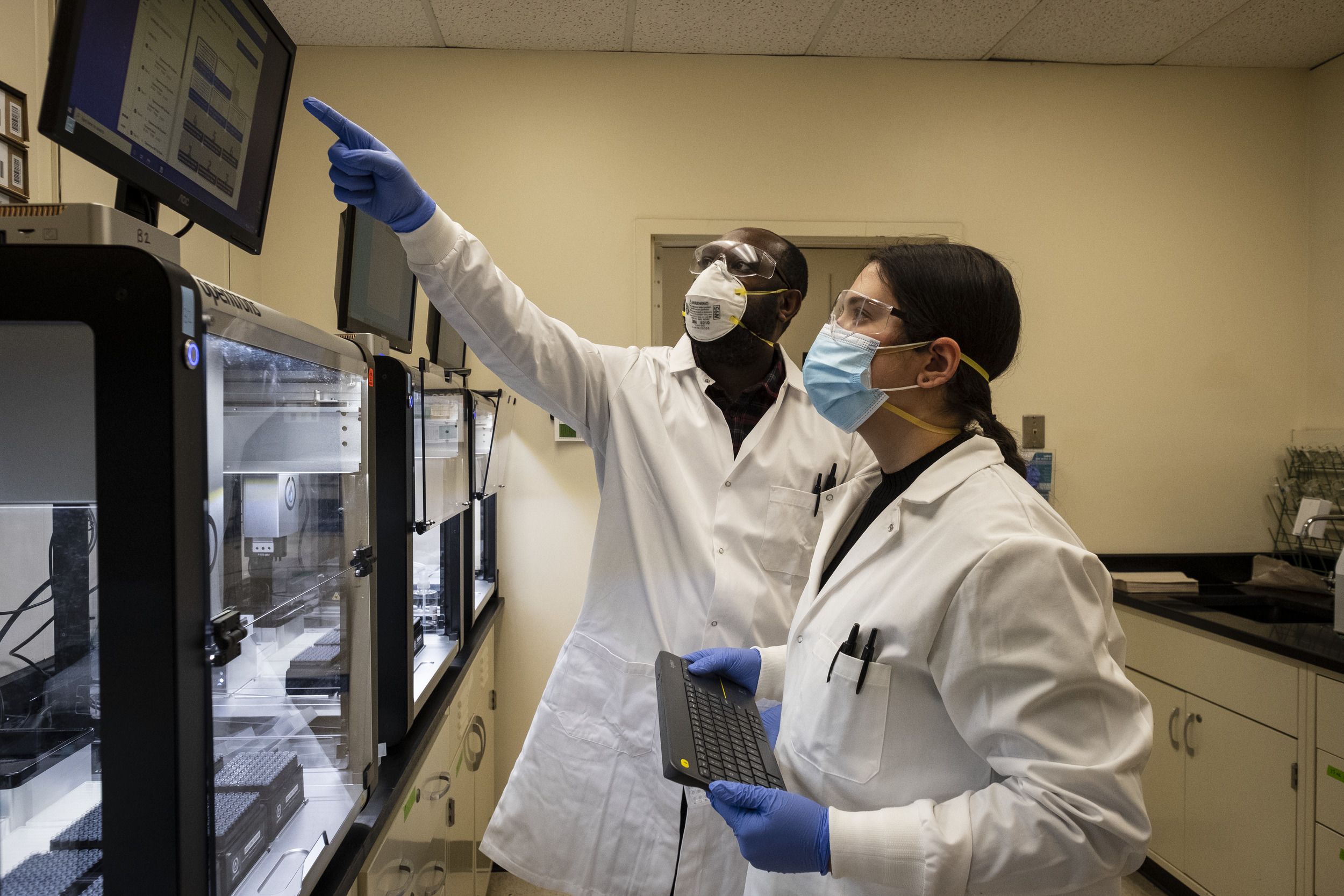

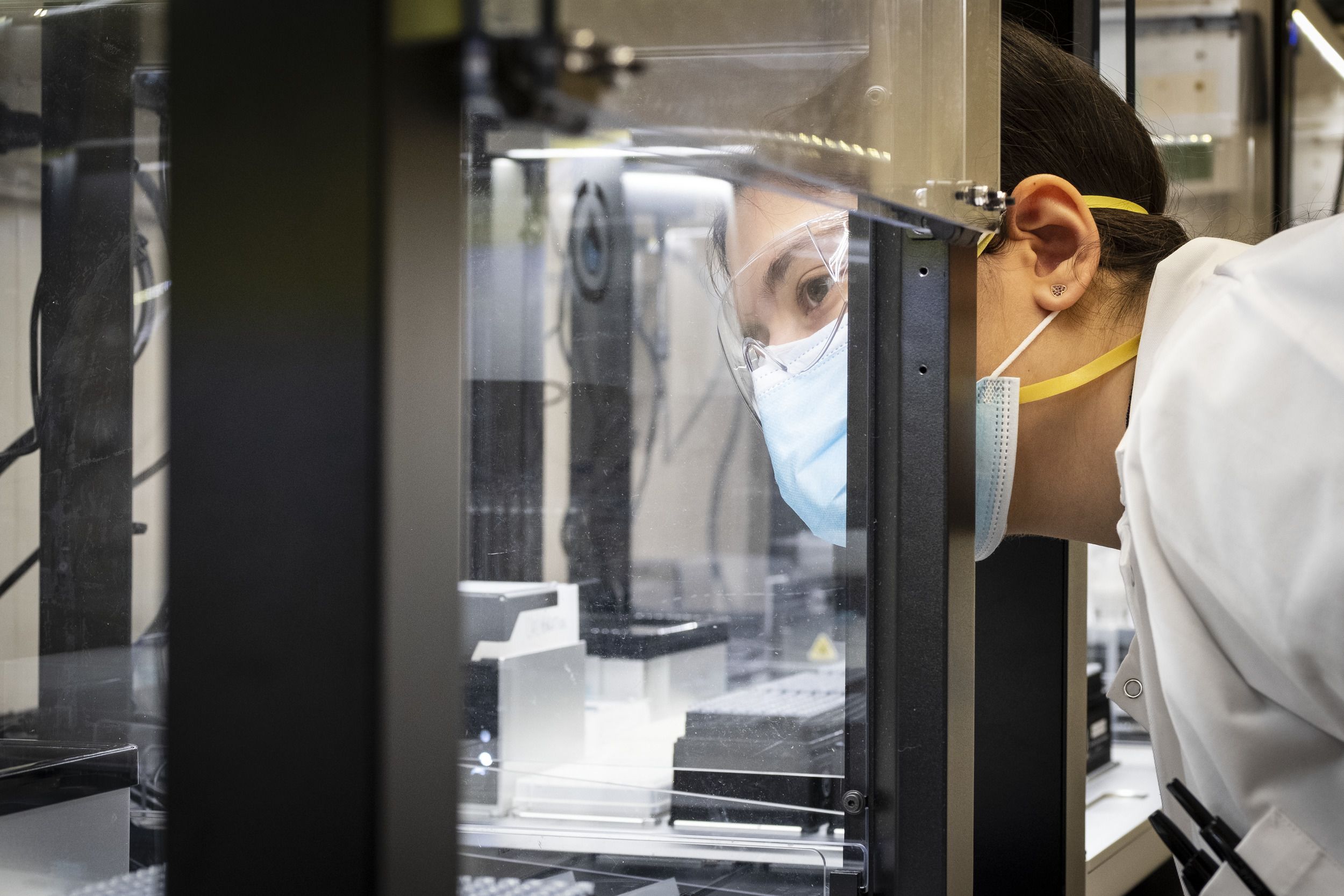

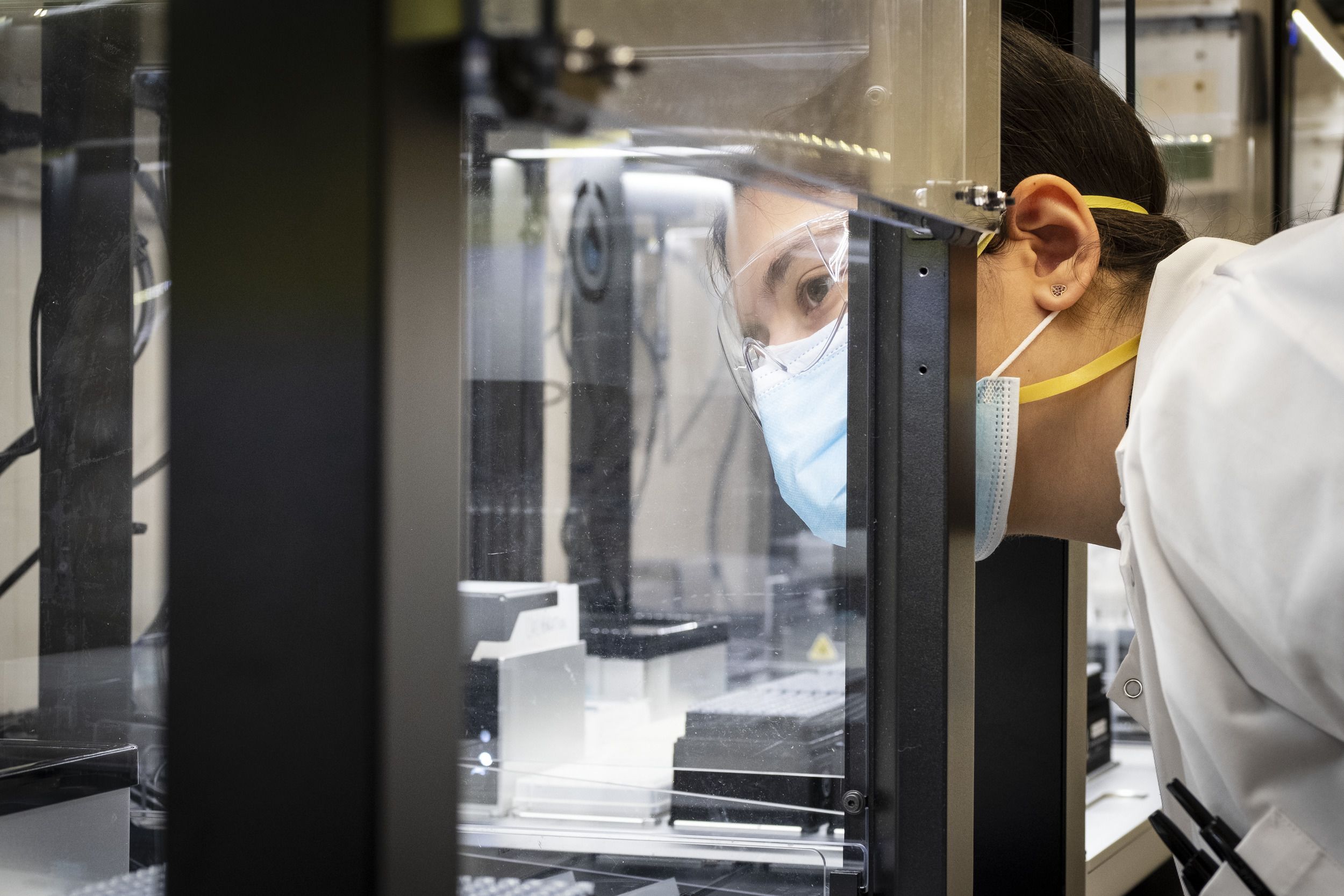

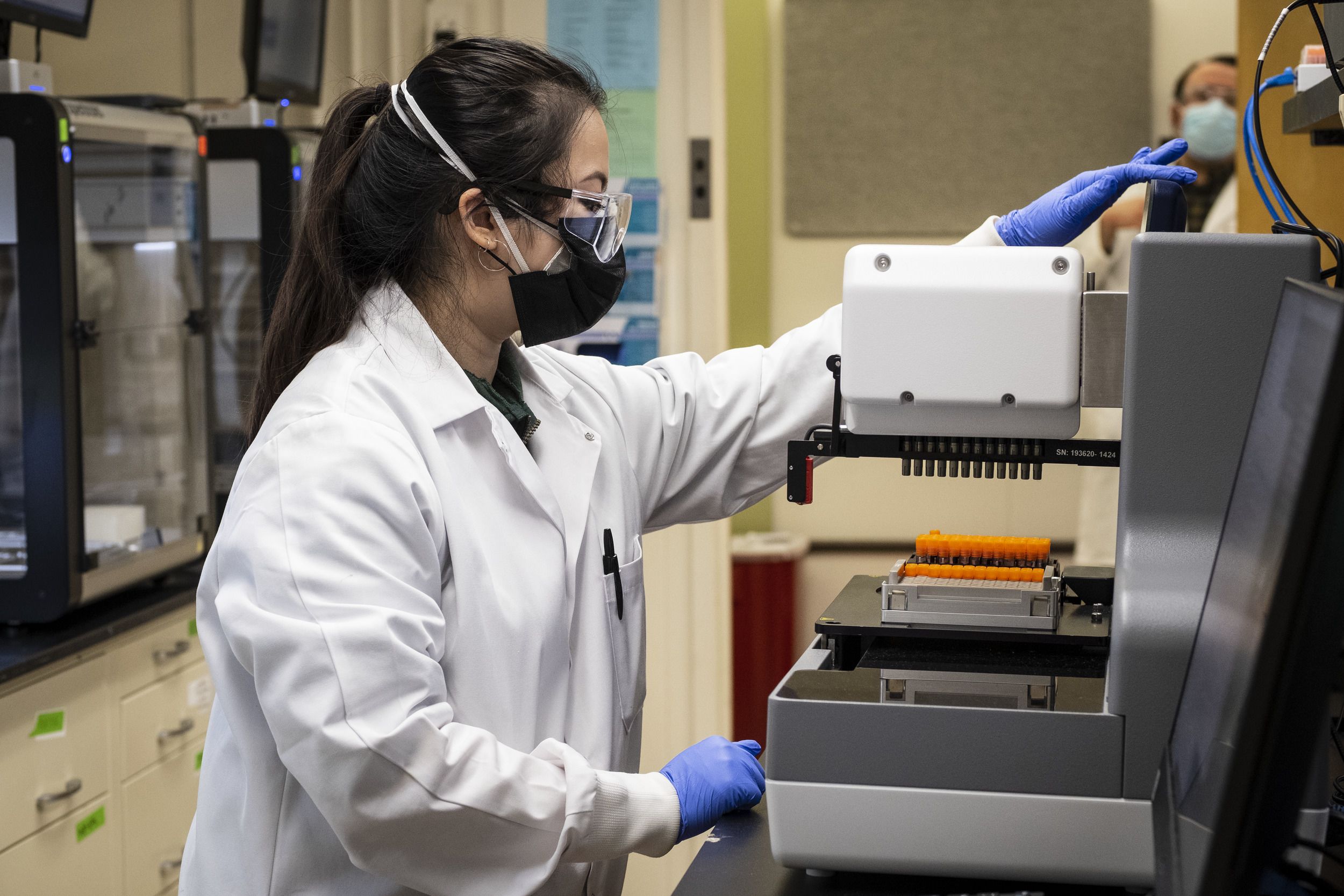

The student deposits the swab they used in the vial and it’s taken to the testing lab, where Gerhard and his team spray it and other vials to decontaminate them. Next, the team records the barcode on each vial so that it can be matched to the barcode assigned to each student when they checked in. Then they begin testing samples, using robots to extract RNA and adding reagents.

“Some labs rely only on the machine to make calls. That is potentially dangerous,” Gerhard said. “You have to look. So I look, then I make the call and process the data into negatives and positives.”

The whole process takes between eight and nine hours and the lab runs approximately 10,000 tests a week.

“The goal of testing isn’t to prevent an individual person from testing positive,” Denys said. Widespread community spread means people are catching COVID-19. “But by testing this often and this many groups, the goal is to prevent or limit the chances of that positive individual causing a cluster of individuals or a cluster causing an outbreak,” he said.

As soon as a positive result is registered, the student receives a secure message via the electronic medical record, followed by an email and a phone call from the contact tracing unit—which has doubled in size—or staff in Denys’ office.

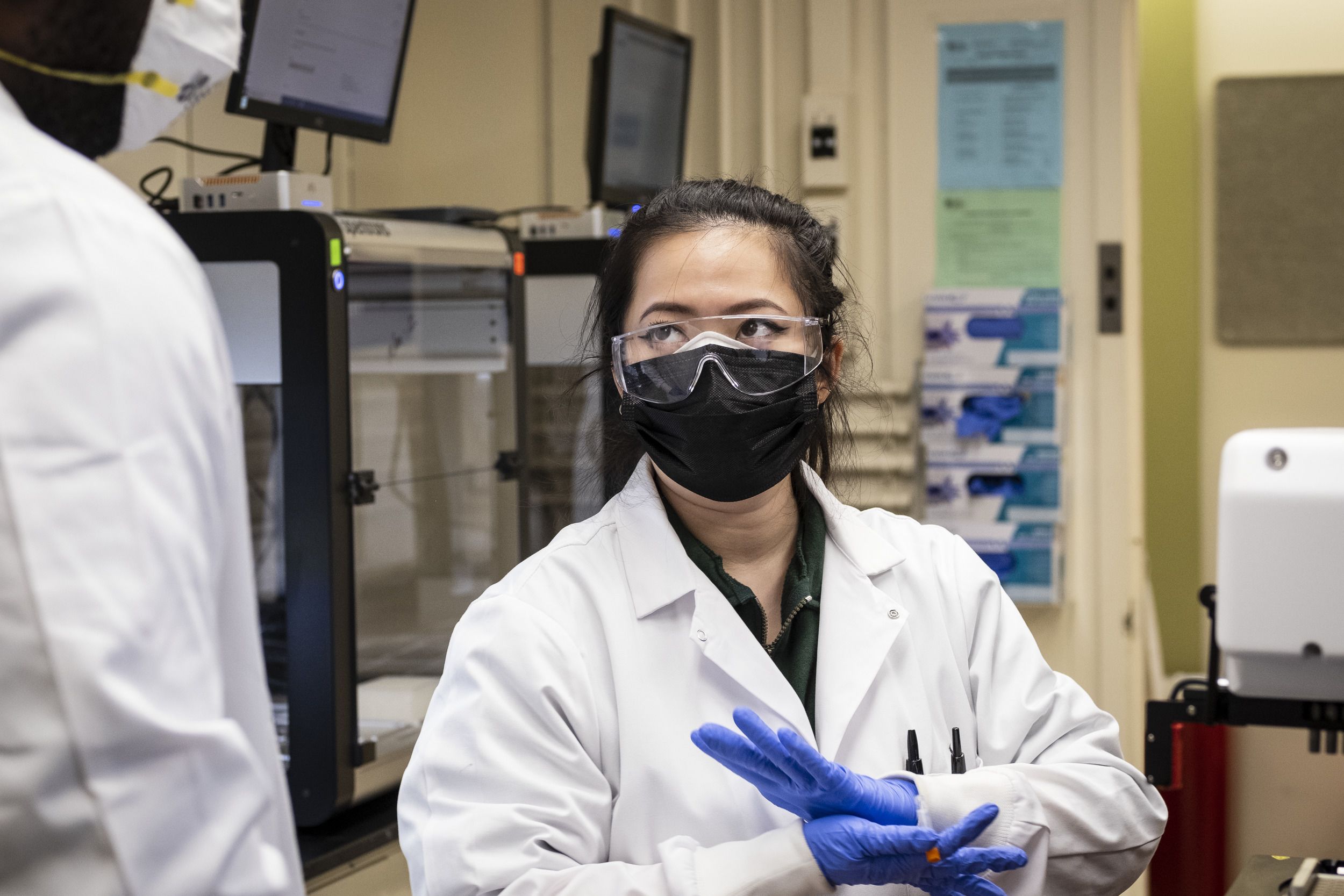

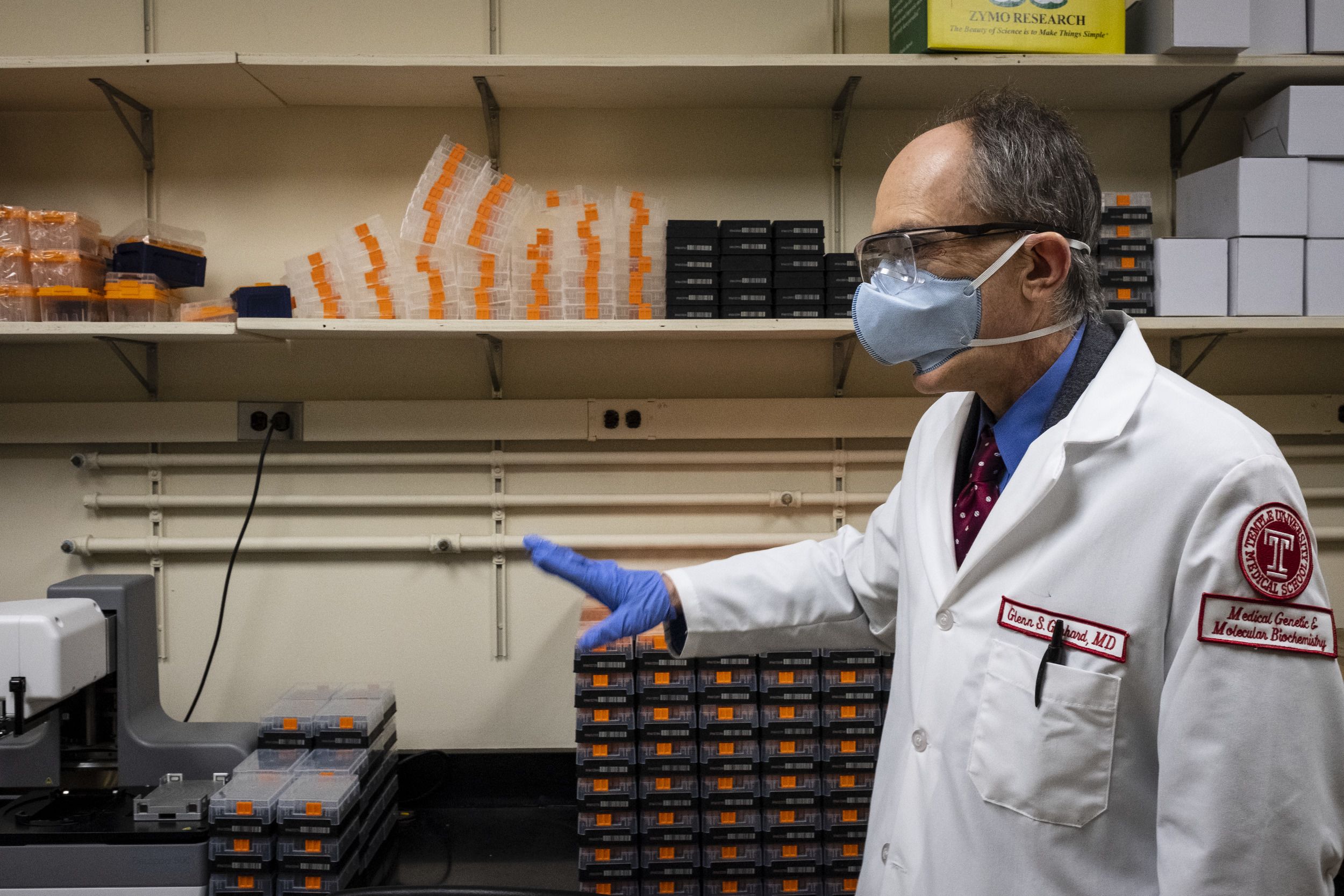

Glenn Gerhard, chair of the Department of Medical Genetics and Molecular Biochemistry at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine and head of Temple’s COVID-19 testing lab.

Glenn Gerhard, chair of the Department of Medical Genetics and Molecular Biochemistry at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine and head of Temple’s COVID-19 testing lab.

The testing lab still faces challenges. Technicians recently had difficulty sourcing the artificially made COVID-19 RNA they use to make sure the testing process works and negative results are accurate. “We do have alternative sources, but every time we lock down one process, something else happens,” Gerhard said. “It’s just a continuous effort to keep the supply chain issues just outside of impacting your actual functioning.”

Everyone involved in the testing keeps going because the program is essential. It’s very important to identify people who have COVID-19 because so many people are asymptomatic and could spread it without knowing it, Denys said. “It’s really vital to getting more people on campus,” he said, “so that we can have more in-person classes, more students living in the residence halls and start getting back to having a more vibrant campus community around.”

“None of this would be possible without the direct financial support of Temple University, of President Englert, Provost Epps and the university Board of Trustees who voted to provide the additional funds necessary to create this testing program,” Daly said. “I think that the testing program reflects our desire—myself as the dean of the school of medicine, the other deans at the other schools and colleges, the provost, the president and the Board of Trustees—to make Temple a safe place in which we can teach our students.”

The program is the embodiment of perseverance conquers. “Failure is not an option,” Denys said. “Saying no and giving up throughout this entire pandemic is just not something any of the people on the team would accept. You just figure out another way to get it done.”