Real-world research

Temple investigators study the pandemic

from all angles

Facing a pandemic of global proportions, researchers across the university changed course to focus on understanding how to best combat

the disease and help people cope.

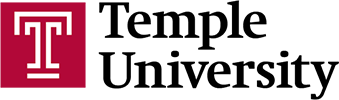

As COVID-19 cases in Philadelphia climbed in the spring of 2020, Nina Gentile, professor of emergency medicine at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine, watched her patients, friends and colleagues contract, and in some cases succumb to, the deadly virus.

Dealing with the stress of treating patients with life-threatening conditions like sepsis, stroke and seizures—and the corresponding pressure to find faster, better therapies—is all part of Gentile’s daily routine as an emergency room physician.

But, when COVID-19 cases started flooding Temple University Hospital, the feeling of urgency rose to a level she had not felt before.

“There’s always an imperative to help patients with emergency conditions as quickly as possible, but I never saw an illness cause as much havoc and misery as this one. Many of my colleagues had not been home in six weeks. We were working around the clock and putting ourselves at risk. We were afraid. We lost a lot of people. We knew if we didn’t find a way to manage it, the virus would spin out of control. For me, this fight was personal.”

Gentile, like many researchers across the university, switched gears during the pandemic to apply her experience to help alleviate the intensity of the crisis. She jumped at the opportunity to lead a Phase 3 clinical trial of the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccine, even though she had not led an investigation that large before.

Others, like Sudhir Kumar and Sergei Pond, put their tried-and-true techniques to work solving various COVID-19-related problems. Normally the pair of biology professors is more comfortable peering millions of years back in time to puzzle out the evolution of the various branches of the tree of life. But since the pandemic, Kumar, Pond, and six of their colleagues at Temple’s Institute for Genomics and Evolutionary Medicine have been focused on a much more recent time frame: When, and where, did the SARS-COV-2 virus first jump to a human being?

“Evolutionary biologists typically look at events that happened in the distant past, so the opportunity to use our expertise to deliver results that may be useful immediately has been quite rewarding,” said Pond.

In total, over the past 15 months Temple investigators have attracted more than $32 million in funding support for COVID-19-related research projects, including 38 clinical trials and 20 basic science studies. That funding comes from a range of both public and private sources, such as the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Small Business Administration, Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Lilly. And more than $33 million in additional COVID-19-related funding has been proposed and is currently pending.

“During this unprecedented period, Temple’s researchers, many of whom are on the cutting edge of their fields, leveraged their professional expertise to investigate the broad-ranging impacts of COVID-19, collaborating to find solutions and put the needs of others first.”

A single-dose solution

As COVID-19 raged across the city of Philadelphia, Temple University Hospital physicians and healthcare workers were on the lookout for the best ways to manage and contain it. They were testing medications that might treat complications, trying antivirals that promised to nip the virus in the bud, anything that could control the infection. But the patients kept coming.

So, when Johnson & Johnson approached Temple looking for places with high incidence of high-risk COVID-19 patients where a Phase 3 clinical trial of their one-shot vaccine could be conducted, Gentile said, “Let’s do it.”

A Phase 3 trial is meant to examine efficacy: Does the vaccine prevent people from getting the virus or improve their outcomes if they do get it, explained Gentile. “I wanted us to be a part of this because I thought we could benefit.”

Temple Health had conducted disease-specific studies before but never a trial on this scale. It required six investigators, 14 coordinators and four data analysts. Faculty and administrators from departments across the medical school and health system stepped in to help, and the health system donated the space.

In the end, the rate of enrollment in Temple’s J&J vaccine trial was the third-highest in the U.S. and eighth-highest in the world, at 531 participants, with 30% being over age 60 and 40% nonwhite.

“For a variety of reasons, including mistrust of healthcare providers, it is always a challenge to engage our nonwhite community in research, but it’s so important to be able to include a diverse population in our studies, so we can measure success accurately for all groups,” said Gentile.

The study is ongoing, but it has already yielded positive results: The J&J vaccine was shown to be 66% effective against preventing disease worldwide, including areas where the COVID-19 variants are prevalent, 86% effective at preventing hospitalization and 100% effective at preventing death from COVID-19.

“Given the rate of success, the vaccine was granted Emergency Use Authorization in March of this year. I was happy that we were able to ‘unblind’ the study at that point, so all participants—even those who had initially received a placebo—could get the vaccine,” said Gentile.

As well, the J&J shot offers other advantages over the mRNA vaccines that require two injections, according to Gentile. “The fact that it is single-dose makes it boatloads easier to distribute among patients that may come into our ER and to those who don’t seek healthcare with regularity,” she said.

Recently, Gentile received permission to administer the vaccine from her emergency room. The program started by offering the vaccine to the homeless population and to community members who are homebound, but now it is available to all patients who accept it.

“After the damage I have seen this virus do, I am so happy to be part of a solution and help to ensure the vaccine is given out equitably,” she said.

Searching for “patient zero”

The first case of COVID-19 human transmission has yet to be identified. However, it won’t be long now, if eight Temple researchers have anything to say about it, that is.

With funding from two awards from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, the team is taking advantage of an unprecedented number of virus genomes sequenced by researchers from around the world to trace the pandemic’s spread back to the likely genetic common ancestor of all the infections—the so-called progenitor genome, the first combination of genetic material to create the virus. In other words, they’re seeking the “mother” of all COVID-19 cases.

Among their findings, which were published in the May issue of Molecular Biology and Evolution journal: Multiple coronavirus infections in China and the U.S. harbored the identifying characteristics of the progenitor in January 2020 and later. This discovery suggests that the virus was spreading worldwide months before the first reported cases of COVID-19 in China.

According to the researchers, the progenitor genome actually differs from genomes of the first coronaviruses sampled in China by three mutations—implying that none of the earliest patients represent the first case that gave rise to all the human infections.

Indeed, they estimate that the SARS-CoV-2 progenitor was already circulating in late October 2019, at least six to eight weeks prior to the first genome sequenced in Wuhan, China.

“Our findings have shifted the conversation regarding SARS-CoV-2’s origins and spread to times much before the first major recognized outbreak in Wuhan, China,” said the paper’s lead author, Sudhir Kumar, Carnell Professor of Biology and director of Temple’s Institute for Genomics and Evolutionary Medicine.

Pond, a professor of biology who focuses on evolutionary genomics, and his laboratory have extensive experience using powerful computers and computational methods to sift through big data sets, including those of viruses. Kumar’s laboratory has developed and investigated many techniques for analyzing genetic data from tumors in cancer patients. In a novel approach to unraveling the evolution of the coronavirus, the research team adapted those cancer techniques to analyze thousands of the more than one million SARS-CoV-2 sequenced genomes.

“The ‘real-time’ nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, with thousands of genome sequences made public daily, created volumes of data and resulted in rapid discoveries never before seen,” said Pond. As a result, the Temple researchers were able to build a trail of mutations that automatically traces back to the progenitor.

“Their innovative methods of using computations to look at the past enables them also to extrapolate the future, allowing us to anticipate changing occurrences,” said Masucci. “This team exemplifies how Temple researchers are pushing the envelope and leading in their fields.”

As to whether the progenitor evolved naturally or was the result of a laboratory leak—a recently revived theory—they lean toward the former hypothesis. “To be able to prove the pandemic was triggered by a lab leak, we would need to be able to compare genomes of lab strains with those found in the lab’s vicinity,” noted Kumar. “Since no such data from lab strains exist, the lab-origin hypothesis remains speculative.”

The team continues to push further back in time to learn about “patient zero” through evolutionary analytics.

“It has been very fulfilling, professionally and personally, to be contributing to the fight against this scourge of humanity by inventing new ways to tame this truly big data,” said Kumar.

Giving COVID-19 the smell test

At the beginning of the pandemic, COVID-19 patients began reporting on Twitter and other social media platforms that they had lost their sense of taste and smell.

“Even though their noses were not congested, as is the case with some colds, they couldn’t smell their coffee in the morning,” said Valentina Parma, a research assistant professor in the Department of Psychology of the College of Liberal Arts. “And it was happening worldwide.”

Before the end of March 2020, these reports triggered the creation of the Global Consortium for Chemosensory Research—a group that quickly grew to 700 researchers from more than 60 countries dedicated to investigating the coronavirus’ chemosensory effects. Their ultimate goal: to develop an evidence-based tool for reporting COVID-19 smell and taste symptoms.

Parma, one of the consortium’s founders, also chairs its leadership committee. She was instrumental in leading the development of a survey and its associated research project that has been singled out by the National Institutes of Health. More than 50,000 people have taken the consortium’s survey, which is available in more than two dozen languages, and 10,000 of them also took a smell and taste self-test to better evaluate their sense of smell.

According to Parma, approximately 70% of people who contract COVID-19 lose their sense of taste and smell, with about 85% of these patients regaining their taste and smell within 60 days of the onset of their symptoms. But for ‘long haulers,’ the remaining 15%, the restoration of taste and smell might take months; a year later, some of those infected still have not regained these senses.

“It’s not unheard of,” said Parma, whose research focuses on the human olfactory senses. “Some viruses produce post-viral smell loss for years.”

In a related development, Parma and her colleagues at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, where she is also a researcher, are continuing to develop and test SCENTinel—a very accurate rapid test that involves a card with three odor patches.

Parma believes such a test would be useful for both coronavirus screening and for use with other health populations as well. “My newborn baby had her hearing and vision checked, but no one checks the sense of smell during a wellness visit,” she said. “COVID-19 has really started a conversation on smell and health, which are linked together in many more ways than most people realize.”

For example, she noted, changes in the sense of smell can pre-date motor disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease, and the inability to name an odor can be a bellwether for dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

For Parma, the past year has been a whirlwind but also extremely gratifying.

“It has been very emotional and fulfilling to see the whole community coming together so quickly with one goal. Not to compete against each other, but to figure out how we could help the most by doing what we know how to do: gather scientific evidence.”

Quantifying COVID-19’s effects on those most vulnerable

In an alarming report, a COVID-19 study involving eight states through May 31 of last year concluded that—while those with intellectual and developmental disabilities were about as likely as members of the general public to contract the virus—they were nearly twice as likely to die from the infection.

“A lot of people in Pennsylvania with intellectual disability or autism live in congregate settings such as group homes, closed environments where they are more likely to have more people—health professionals, staff and other residents—interacting with them every day,” explained Sally Gould-Taylor, associate research professor and executive director of Temple’s Institute on Disabilities. “Unlike people who were able to stay home and limit their contacts, their ‘bubble’ remained much bigger.”

That has even been true for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities who live at home but who still rely on support staff and healthcare professionals to provide in-home services.

The Institute on Disabilities, which is part of the College of Education and Human Development, played a critical role—and continues to do so—in helping Pennsylvania Advocacy and Resources for Autism and Intellectual Disability evaluate the risk of COVID-19 to people with intellectual disability or autism.

Pennsylvania Advocacy and Resources for Autism and Intellectual Disability joined with the Institute on Disabilities in completing the study in Pennsylvania. Syracuse University, New York Alliance for Inclusion and Innovation, and the American Network of Community Options and Resources assisted in the study as well.

In an updated analysis of the same data through January 2021, preliminary results indicate the increase in fatality risk has worsened. Even though the infection rates of people with intellectual disability or autism is now somewhat lower than the general public—5.62% as compared to 7.57%—the probability of such people dying from the infection has more than doubled.

Katey Burke, an assistant research professor in special education who has worked with Gould-Taylor on the study, hypothesizes that the infection rates for people with intellectual disabilities or autism may have declined due to more widespread testing, as well as COVID-19 mitigation strategies within the intellectual and developmental disabilities provider community.

“People with intellectual and developmental disabilities have more comorbidities, which are a huge predictor of COVID-19 fatalities, particularly if the comorbidities involve the heart or lungs. But another study this year concluded that, irrespective of comorbidities, having an intellectual disability was the strongest independent risk factor for being diagnosed with COVID-19 and, other than age, the strongest independent risk factor for dying from it.”

For all these reasons, the Institute on Disabilities has strongly advocated for continued government support. At the end of last year, Gould-Taylor noted, “Pennsylvania and the federal government provided temporary support, which absolutely helped save lives. But that stopgap funding is essentially gone, and we need more support.”

According to Gould-Taylor, the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, signed by President Biden in March, is expected to provide some support. The American Jobs Plan, the Biden Administration’s infrastructure bill that Congress continued to negotiate in July 2021 could provide more relief—both for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and the support workers they depend upon.

“All industries are dealing with staff shortages, but that’s especially true for service providers who are having a hard time maintaining the level of staffing that they need,” said Gould-Taylor.

Funded by a grant from the U.S. Administration on Community Living, Temple’s Institute on Disabilities has also helped increase vaccine access for Pennsylvanians with intellectual and developmental disabilities with a number of measures. These include opening up a dedicated call center and, through TechOWL—Pennsylvania’s designated Assistive Technology Act Program—providing assistive technology and accessible content for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities at many vaccine centers throughout the state.

Teasing out COVID-19’s impact on people with substance use disorders

While COVID-19 challenged every organization and population, its effects have disproportionately affected more vulnerable groups, such as individuals with substance use disorder—as well as the organizations that provide life-sustaining services to those who meet that criteria.

Funded by a $100,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Drug Abuse, Sarah Bauerle Bass—an associate professor of social and behavioral sciences and director of the Risk Communication Laboratory at the College of Public Health (CPH)—has been investigating both those impacts.

Even before the pandemic, the statistics were staggering: More than 23 million Americans were experiencing substance use disorder, with only 10% receiving treatment.

Bass’ study seeks to learn how people with substance use disorder have prioritized COVID-19 among their many challenges. Her study involves clients of Prevention Point Philadelphia, a Kensington-based nonprofit committed to reducing the harm associated with drug use.

“If you don’t have a place to stay, that’s going to be your priority, not whether you’re wearing a mask and standing six feet away from people,” she said. “How does this rank within the things that they have to worry about on a daily basis, such as ‘Where am I going to sleep tonight, what am I going to eat or even how am I going to get access to the substances that I use? Or even other diseases like HIV or hepatitis C that they also might come in contact with.”

She also wants to understand how COVID-19 has impacted providers such as Prevention Point Philadelphia. “When everything was shut down, and they really couldn’t allow anybody inside the building, they had to figure out how they would do things like syringe exchanges,” she said. “They had to switch medical services to a mobile van. They have shelters where people sleep, and a drop-in center, and people come in for meals. They had to rethink all of that.”

Bass has interviewed and surveyed many of Prevention Point’s staff and clients. Hoping to complete her research by year’s end, she is now conducting an analysis of the planning the organization did in hopes of developing a “best practice” blueprint for other service providers, should a similar outbreak occur in the future.

One focus of her inquiry: how information about COVID-19 has been communicated and the clients’ overall feelings about the virus. This includes vaccine hesitancy, which she believes is about 20% of individuals with substance use disorder—similar to the general population. “While they trust Prevention Point, a lot of these individuals don’t have a lot of trust in healthcare organizations or other outside groups,” explained Bass. “This can affect the likelihood that someone will get vaccinated.”

In April, with funding from Temple University Hospital, Bass and CPH began studying vaccine hesitancy in a broader population throughout Philadelphia to understand how best to communicate with hesitant groups and what messages might best resonate. Additionally, with an $800,000 grant from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, Bass is working with other CPH faculty to promote vaccine availability in underserved areas of the city through a program called Rapid Vax. This project brings vaccination clinics directly to communities, partnering with about 15 community sites, including Philadelphia Housing Authority locations and Prevention Point.

“Logistically, the pandemic has certainly made my research more difficult,” said Bass. “But, for someone like me who has devoted her entire career to risk communication, for my many years of professional experience to come to fruition in a way that has enabled me to make a meaningful contribution now has been personally very gratifying.”