Stepping into

the spotlight

When the public had questions,

these Temple faculty members

came through with answers.

It’s no secret why journalists rely so heavily on quotes from scientists, doctors, university faculty and other experts. Their voices lend credibility, objectivity and often critical information to news reports.

In March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit the U.S. with full force, a torrent of pandemic-related stories proliferated across news media. During such an unprecedented time, when the world was facing so many unknowns, reporters sought trustworthy sources from numerous fields to provide answers and explain what was happening to their readers and viewers.

Among those called on to lend their knowledge on various aspects of the pandemic were several Temple faculty members. For some, it was familiar territory; and for others, it was a brand new venture.

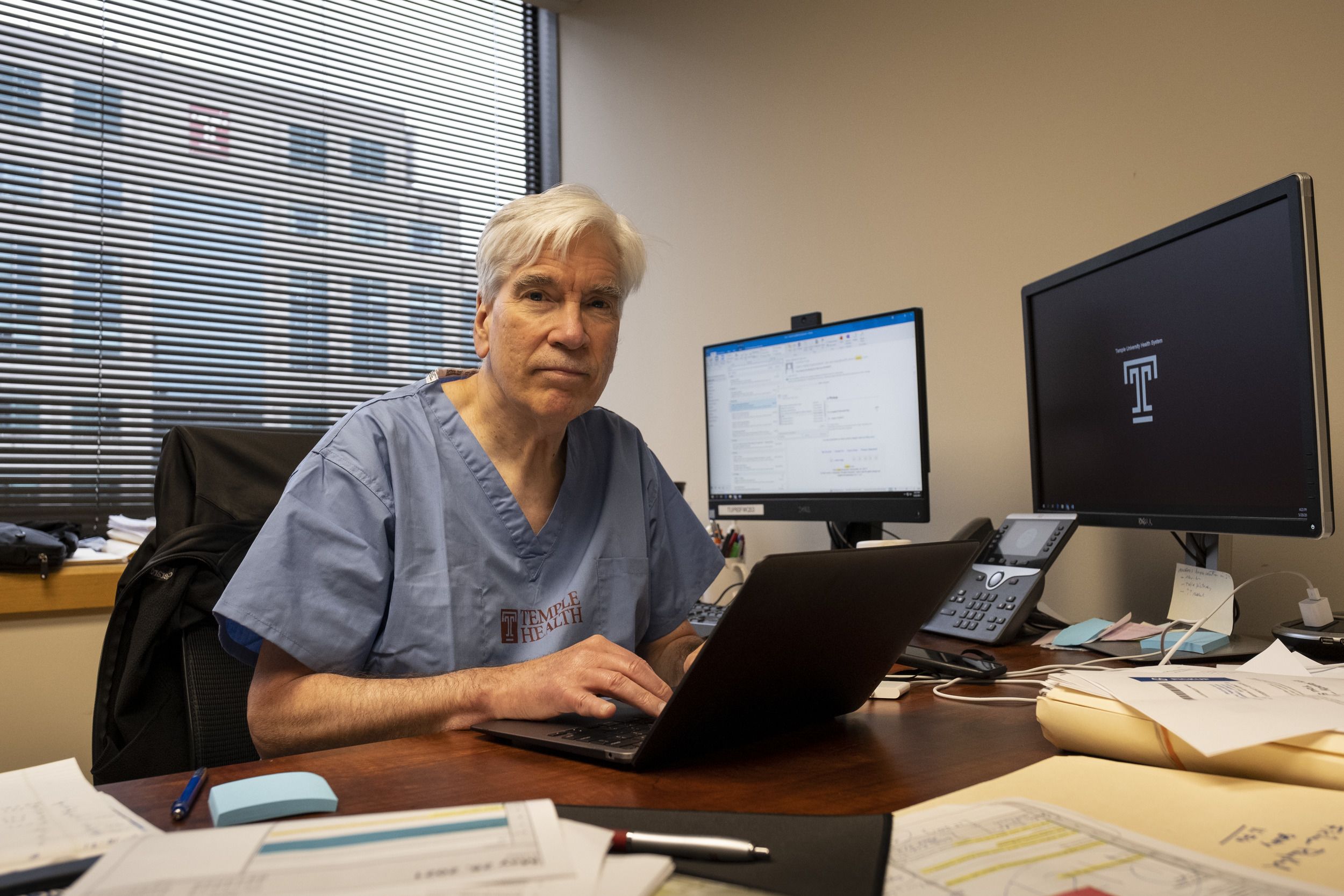

Patients first

As professor and chair of thoracic medicine and surgery at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine and the director of the Temple Lung Center, Gerard Criner has been at the forefront of new treatments and discoveries, talking to the media for years about pulmonary disease and airway disorders.

When asked what was different about being called on to speak to reporters during this critical time in our history, his answer was, “Nothing.”

“I didn’t see my role during this crisis as any different than my role on any other day. I just focused on what needed to be done and at Temple that’s what we all did,” said Criner. “Our hospital had the hardest road to climb in terms of number of COVID-19 patients and severity of illness, and we had the best patient outcomes because we stayed focused on doing what needed to be done and putting our patients first.”

Criner led the charge against the coronavirus on multiple fronts, working around the clock to save lives, ensure the safety of his staff, and investigate new and better treatments. And he was featured in numerous stories like The Philadelphia Inquirer’s harrowing day-in-the-life piece printed in April 2020. It looked inside Temple University Hospital’s Esther K. Boyer Pavilion, which was converted to a COVID-19 ward in the earlier days of the pandemic. In the story, he explained how he had been talking for months with colleagues in Wuhan, China, strategizing about how to safely create a dedicated space for COVID-19 patients, away from people with other illnesses.

On May 4, 2020, Criner was a subject in Philadelphia magazine’s story, “Philly researchers are speeding up the clinical research process with coronavirus trials” about the accelerated clinical trials in the race for a COVID-19 cure. In it, Criner, who was the lead investigator for four out of 30 local trials, explained how he juggled 18-hour days in the hospital, treating patients, doing rounds and overseeing the logistics of the trials. In a quote that summed up the spirit of the medical community throughout COVID-19, he said, “It’s a lot, but we’re doing whatever needs to be done.”

That month he was also called on by NBC10 to explain why the virus was so intense and why some were affected more than others, and he talked to the Washington Post later in the year about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines. In every instance, Criner explained, “The one thing I was trying to do, whether I was talking to my colleagues or to my patients or members of the media, was to be truthful and stay focused on the science.

“That approach exemplifies what’s in our DNA here at Temple Health,” added Criner.

“It’s like a whole other job, trying to stay on top

of the constant news and publications

and data that is coming out of it.”

Just the facts

The pandemic also thrust the university’s public health experts into the spotlight, among them three faculty members from Temple’s College of Public Health.

“Before COVID-19, I had no other experience speaking with the media,” said Aimee Palumbo, assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics. “I was very nervous at first about how my words would be portrayed, if the writers would quote me accurately, and if the story would capture the spirit of what we discussed.”

The first story Palumbo was tapped for was an article in The Philadelphia Inquirer in late April 2020, about COVID-19 outbreaks in Montgomery County prisons. As the months passed, the topics she was asked to speak about shifted; she went on to give her input in articles and radio stories about the risks of taking Communion, safe Halloween practices for school-aged children and parents, and pandemic trauma’s effects on memory. No matter the angle of the story, Palumbo always strived to keep the big picture in view.

“One of my areas of study is social exposure: How our social lives and where we work and live influence our health,” she said. “I was always trying to focus on the disparities we were seeing across different areas, with infection rates so high in certain communities.”

Palumbo put pressure on herself to strike the right balance between urging the public to take the pandemic seriously without causing fear or panic. As an expert voice, there was also an expectation that she was always abreast of most recent research and developments surrounding COVID-19.

“There are so many aspects to the pandemic. It’s like a whole other job, trying to stay on top of the constant news and publications and data that are coming out of it,” she said. “It could be exhausting, but I saw it as a duty to share my knowledge when I was asked.”

Palumbo’s colleague Sarah Bauerle Bass, associate professor in Temple’s College of Public Health and director of the Risk Communication Laboratory, was also frequently heard from during the pandemic. Her research focuses on how crafting public health messages to various audiences can influence decision-making. The media appearances around COVID-19 required her to step back into a role from earlier in her career. In the 1990s, Bass was the public information coordinator for the West Virginia Department of Public Health during the HIV crisis. In response to the media requests she received during the COVID-19 pandemic, Bass revisited the skills and strategies she developed while working in that high-profile position.

“The psychology of a crisis is the same no matter what it is,” she said. “You have the same responses from the public and if you don’t respond in a way that the public needs at a certain time, you’ve got problems.”

Two major challenges in this specific crisis, according to Bass, were the politicization of the COVID-19 pandemic and the huge impact of social media on public perception. One tactic that she believes can help to combat disinformation is borrowed from commercial marketing approaches that tap into human emotion. So, in her media appearances, Bass homed in on the public’s emotional response, and shaped her messaging around that in order to convey the facts.

“I think we have to try to use some of the same tactics. I know that sounds weird, but we have to understand that people respond emotionally when they’re at risk, and disinformation feeds on that,” she explained.

In January 2020, Bass started paying attention to the news coming out of China, and was not surprised when the media began calling her department in February. She first spoke with a television crew from NBC10 about how people would feel about the pandemic, and figured journalists might start reaching out from time to time. What she didn’t imagine was just how often she’d field media requests, ranging from The Philadelphia Inquirer to a Philadelphia community podcast to International Business Times.

“It was everything I teach in the classroom and every aspect of what I’ve done in my professional life, happening in real life,” she noted. “At the time, I was teaching a graduate-level health communications class, and we started every class examining the media and government coverage of COVID-19, how people were responding, and what was and wasn’t working.”

What wasn’t working, she observed, was “pretty much everything.” She and her students watched and discussed in real time how the federal government abandoned traditional crisis communication principles.

“One of the tenets of crisis communication is that people don’t panic if you tell them the truth. Even if you say you don’t know all the facts, people are better at accepting that than feeling like you’re lying to them,” Bass said. “When you’re not giving clear directives or those directives are so diverse, like do or don’t wear masks, it becomes hard for the public, and they just give up.”

Bass says that in this regard, she approached every media inquiry with the same simple directive for herself: “What is it that I need to say that will get across to people clearly so they can understand what’s happening?”

“One of the tenets of crisis communications is that people don’t panic if you tell them the truth.”

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Krys Johnson, assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics in the college, had never been quoted in the media as an expert voice. It was her undergraduate degree in health education and promotion that prepared her to be in the public eye.

“My undergraduate degree emphasized taking academic conclusions and making them meaningful to the general public,” Johnson said. “Without that training, I don’t think so many reporters would have wanted to speak with me!”

Plenty of reporters wanted to speak with her, and throughout 2020 she found herself inundated with requests, taking calls on the way to campus, between classes and into the evening hours. She spoke on various issues surrounding COVID-19, such as professional sports “bubbles,” the risk of college students traveling home for the winter holidays, and the Johnson & Johnson vaccine pause. From PhillyVoice to Good Morning America, media outlets big and small leaned on Johnson to answer questions and share the most up-to-date scientific recommendations with their readers and viewers.

In these interviews, one question that Johnson remembers hearing again and again was: “When will this be over?”

“I couldn’t necessarily answer that one, but I could tell people what they could do to protect themselves, or even what I was doing to protect myself, so people would have more context about how their environment might affect their likelihood of becoming ill.”

Like her College of Public Health colleagues, Johnson prepared for interviews by reading up on the latest research and findings. She also quickly learned that for many interviews, especially television spots, crafting a short and sweet message was key because of time limitations.

“This is the opposite of how we’re trained to write and rationalize in academia,” she noted.

Overall, Johnson described the experience of being called upon to speak to the public about such a crucial—and sometimes controversial—topic as both heartening and stressful, particularly when public health recommendations turned partisan.

“I just wanted to empower the folks in Philly and the surrounding areas with facts about how to protect themselves,” she said. “Scientists and the gift of continuous scientific discovery enabled officials to put effective public health recommendations into place. I was happy to be part of interviews and spots where science led the conversation.”

Teen spirit

Laurence Steinberg, the Laura H. Carnell Professor of Psychology at Temple, is one of the world’s top experts on adolescence and the adolescent brain. As a leader in the field, he is often turned to for input on questions regarding teen behavior, including impulse control and risk-taking. His work draws on the latest scientific findings to challenge old stereotypes about adolescence and offer parents, educators and policymakers practical tips for improving the well-being of young people. Steinberg’s research on teen behavior has played critical roles in several U.S. Supreme Court rulings that have changed the direction of juvenile justice—one ruling abolished the death penalty for juveniles, another outlawed life-without-parole sentences in nonhomicide cases for those under 18.

As the author of many articles and books, he has appeared on CBS Morning News, Today, Good Morning America, 20/20, Dateline, PBS NewsHour and The Oprah Winfrey Show, and is a frequent consultant on adolescence for print and electronic media, including the New York Times and NPR.

When teen behavior on high school and college campuses was a rising concern in terms of virus spread, the media again turned to Steinberg for guidance. His advice seemed to strike a nerve. Informed by decades of research, he asserted that safety measures and separate dormitory pods just weren’t going to work with this population, citing how risky behaviors like reckless driving, violence, unsafe sex and binge drinking peak during late adolescence.

“The idea that you could get college students in shared spaces to avoid having contact with their peers is just kind of crazy,” Steinberg said.

“Moreover, interventions designed to diminish risk-taking in this age group, such as attempts to squelch binge drinking on campus, have an underwhelming track record,” he wrote in a June 2020 opinion piece for the New York Times. “There is little reason to think that the approaches proposed to mitigate transmission of the coronavirus among college students will fare any better.”

Then in April 2021, Steinberg put the minds of parents worrying that the pandemic year had caused their youngsters to miss key developmental milestones at ease by explaining the science behind how their kids’ brains develop.

“Do kids need certain kinds of experiences at this point in their lives in order to be able to develop normally? Yes, but there’s no reason to think an interruption like this is going to cause permanent damage,” he said. “The plasticity afforded by the adolescent brain at this age allows for recovery.”