A recipe for success

Keeping the Temple University community safe and healthy during the COVID-19 pandemic depended largely on two factors: regular testing of students, faculty and staff to prevent an outbreak and the widespread distribution of vaccines to Temple community members. The efforts undertaken to carry out these two critical activities (at the same time, no less) were, in a word, extraordinary.

On the morning of Aug. 13, 2021, the city of Philadelphia announced a new mandate: All students, faculty and staff members at a university or college in the city must be fully vaccinated by Oct. 15. (The deadline was later extended to Nov. 15.)

For Temple University, Philadelphia’s largest institution of higher education, this was a turning point and its leadership and campus health administrators acted accordingly.

Within 15 minutes, Mark Denys, senior director of student and employee health services, and the rest of Temple’s COVID-19 Steering Committee gathered on a Zoom call.

The committee then worked diligently to get the message of the vaccine mandate out to the campus community, using President Wingard’s #VaxUpTU campaign as the message’s backdrop.

“Temple’s position has been the same since vaccines became readily available. We always said that we believed that everyone who could get the vaccine should do just that, but this accentuated the urgency,” Denys said. “Just strongly encouraging our community to get the vaccine was no longer enough and just having a mandate was not enough, either. It takes a lot of effort to get a university of our size into compliance. We had to make a plan to quickly achieve this goal, and I think this is one of the best examples of the Temple community really coming together.”

Come together they did. By Nov. 19, more than 97% of the Temple community reported as fully vaccinated, representing nearly 41,000 students, faculty and staff. Another 2.5% had received approved medical or religious exemptions.

But as the goal was met, the path to get there was not easy. And could be traced all the way back to January 2021 when the COVID-19 vaccines first became available.

That was when Temple’s Office of Student and Employee Health Services began planning to run its own invitation-only vaccine clinics out of two Main Campus buildings, one a then-vacant residence hall and the other an administrative building with classrooms.

Looking back at 2021 by the numbers reveals an astounding deployment of resources to protect the Temple community and its neighbors.

At James S. White Hall, between March 31, 2021, and June 23, 2021, 5,796 doses of the vaccine were distributed to Temple students, faculty, staff and community members during 18 clinics operated by 34 staff members and 18 volunteers.

At Paley Hall, the numbers are equally impressive: 5,445 doses were distributed during 33 clinics.

But as impressive as those numbers are, they only tell part of the story.

"It takes a lot of effort to get a university of our size into compliance. We had to make a plan to quickly achieve this goal, and I think this is one of the best examples of the Temple community really coming together.”

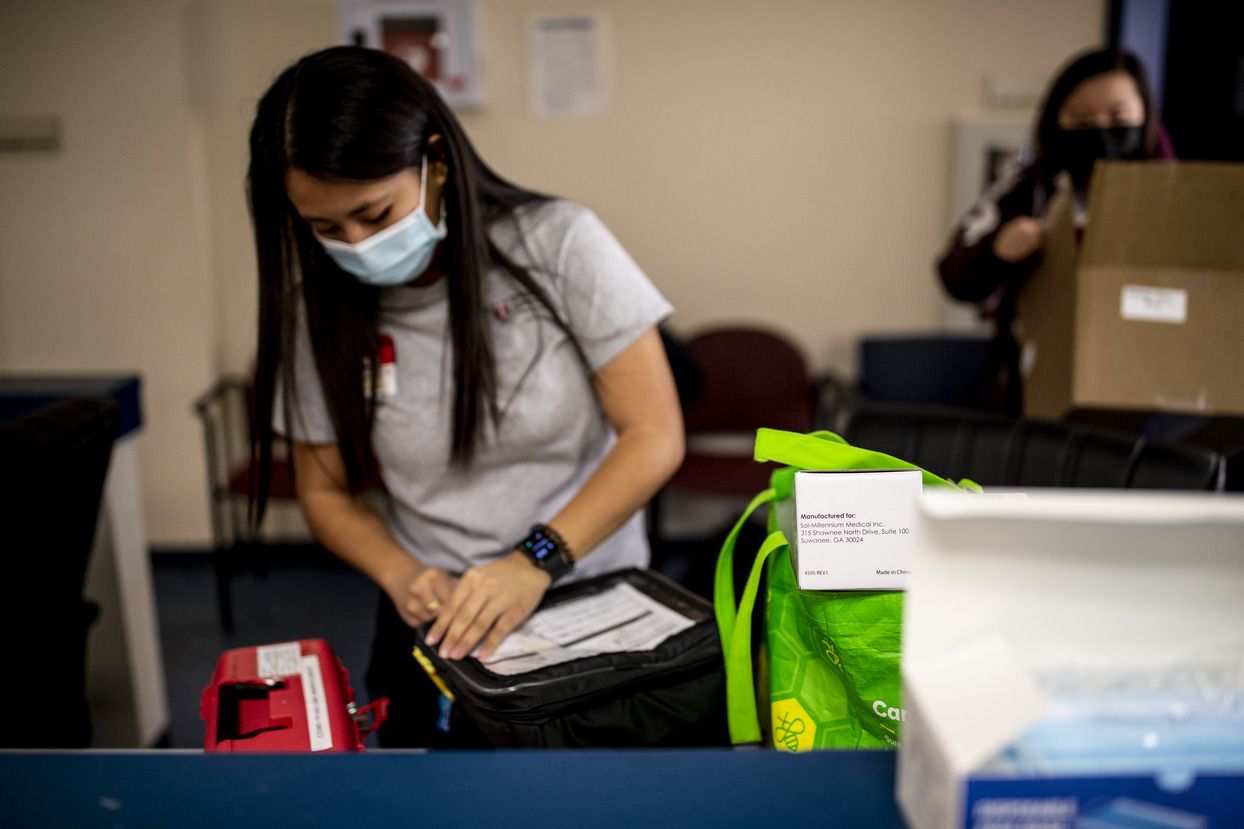

A vaccine clinic was held for international students at Paley Hall. (Photography by Ryan S. Brandenberg, CLA ’14)

A vaccine clinic was held for international students at Paley Hall. (Photography by Ryan S. Brandenberg, CLA ’14)

Vaccine clinics were set up around Main Campus, including in Paley and James S. White halls. (Photography by Ryan S. Brandenberg, CLA ’14)

Vaccine clinics were set up around Main Campus, including in Paley and James S. White halls. (Photography by Ryan S. Brandenberg, CLA ’14)

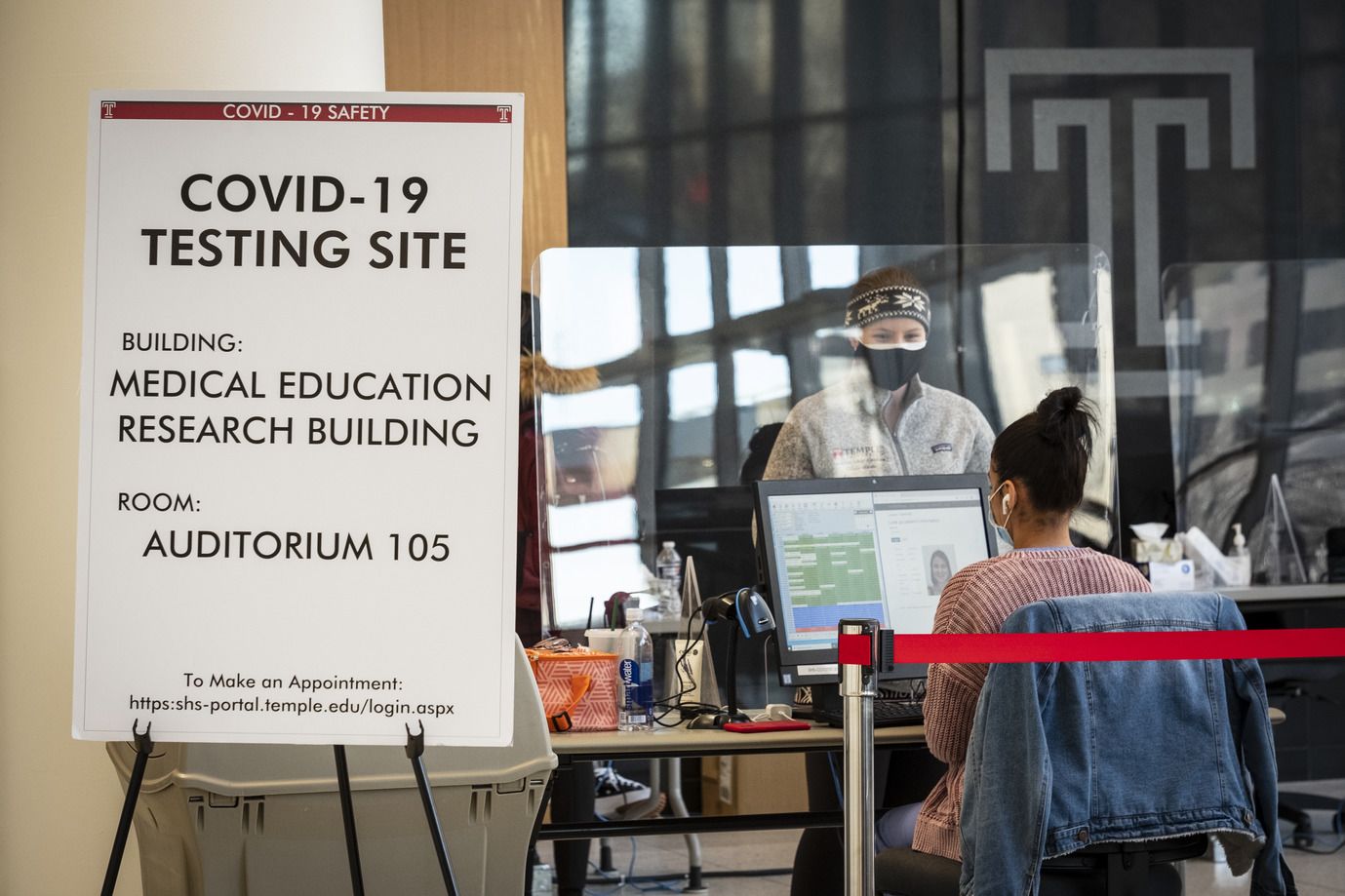

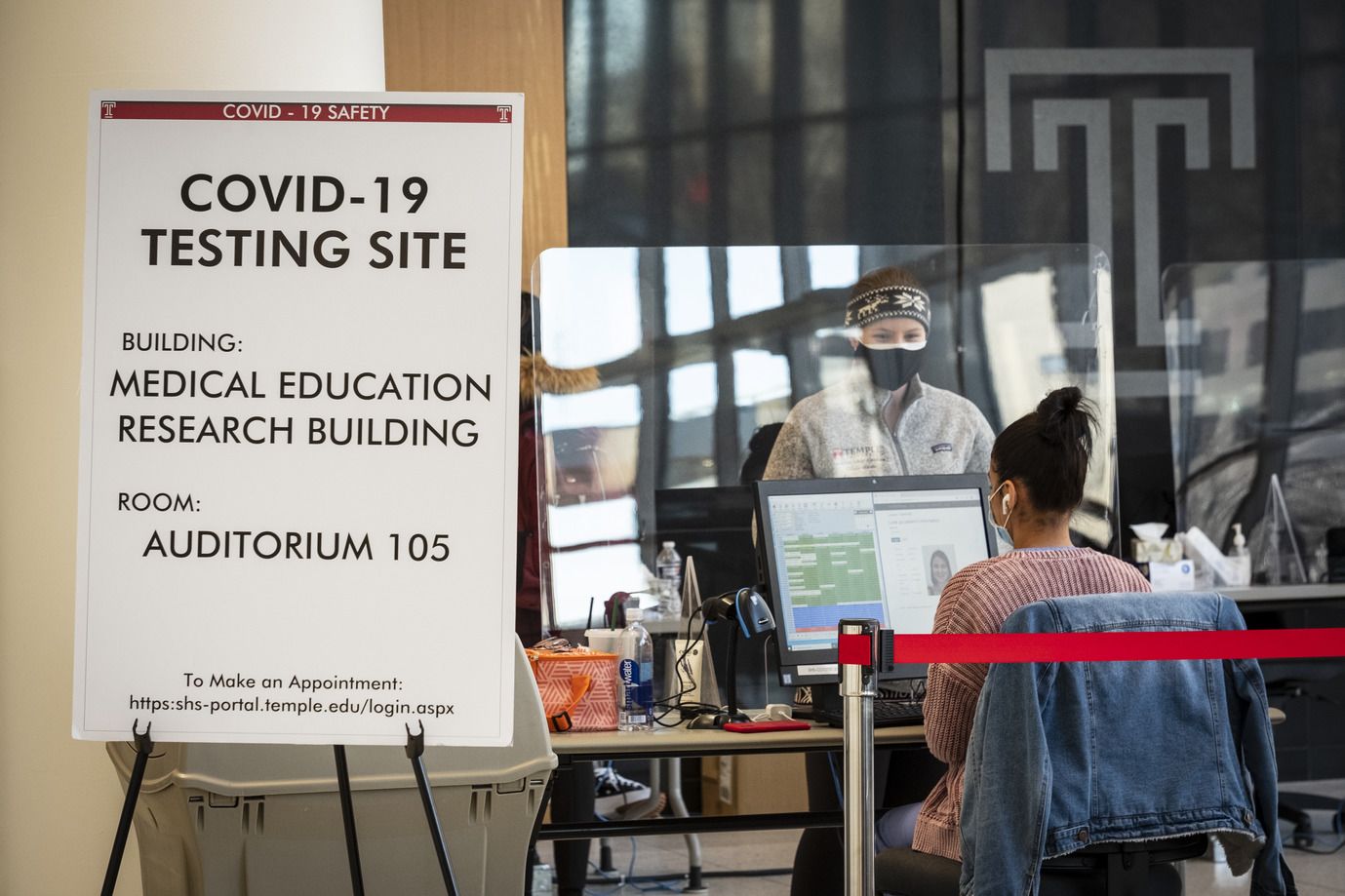

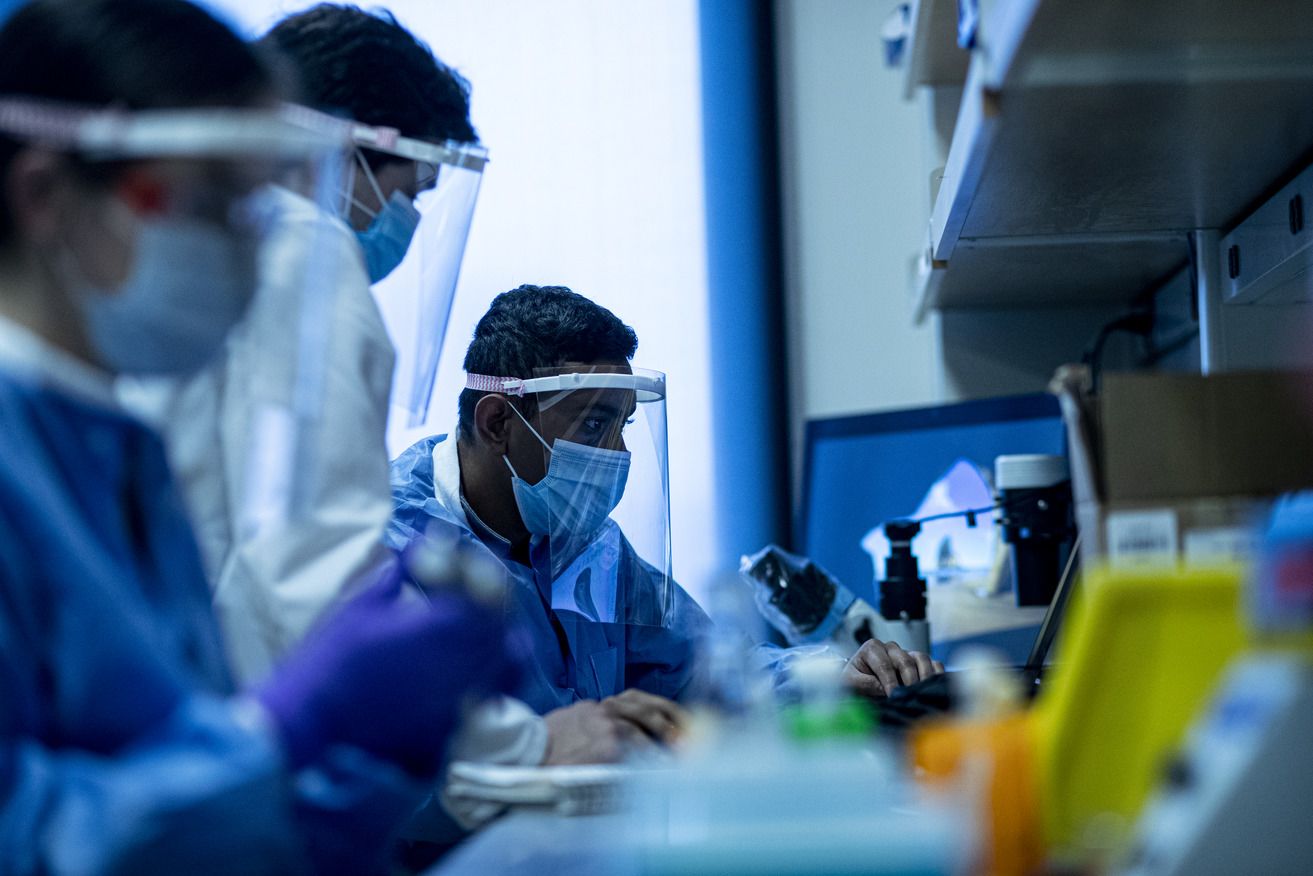

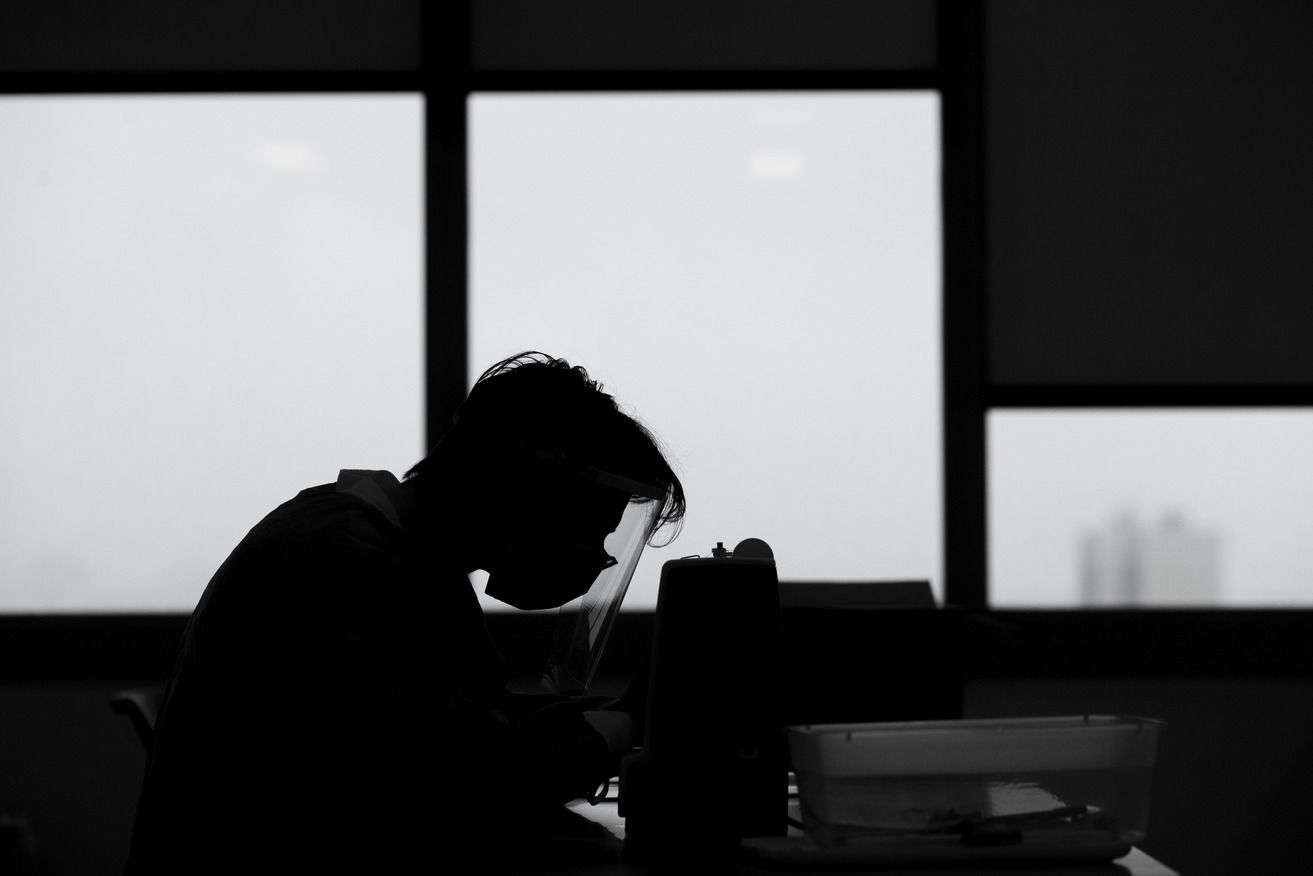

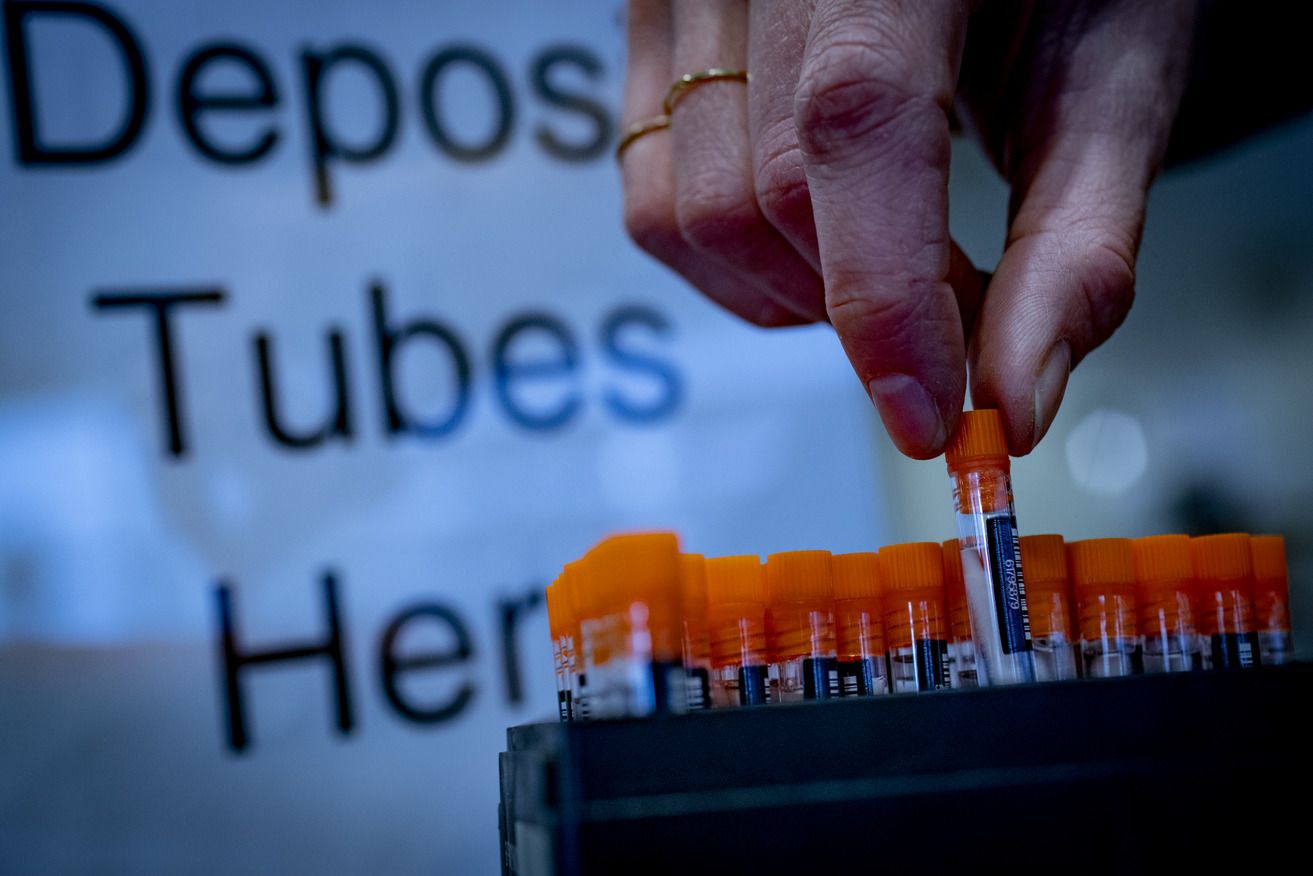

Temple developed its own, in-house COVID-19 testing program, which included various testing sites. (Photography by Ryan S. Brandenberg, CLA ’14)

Temple developed its own, in-house COVID-19 testing program, which included various testing sites. (Photography by Ryan S. Brandenberg, CLA ’14)

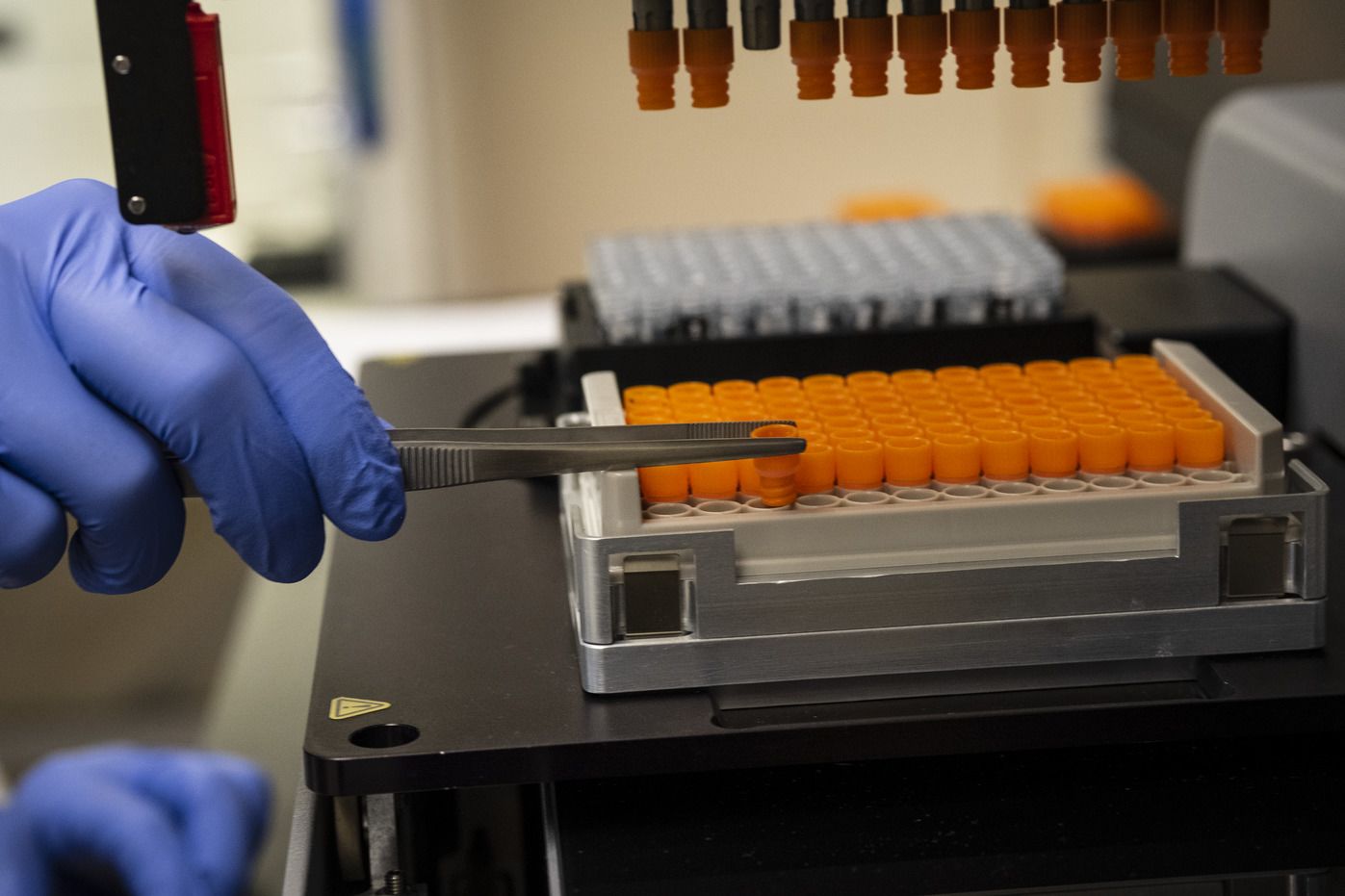

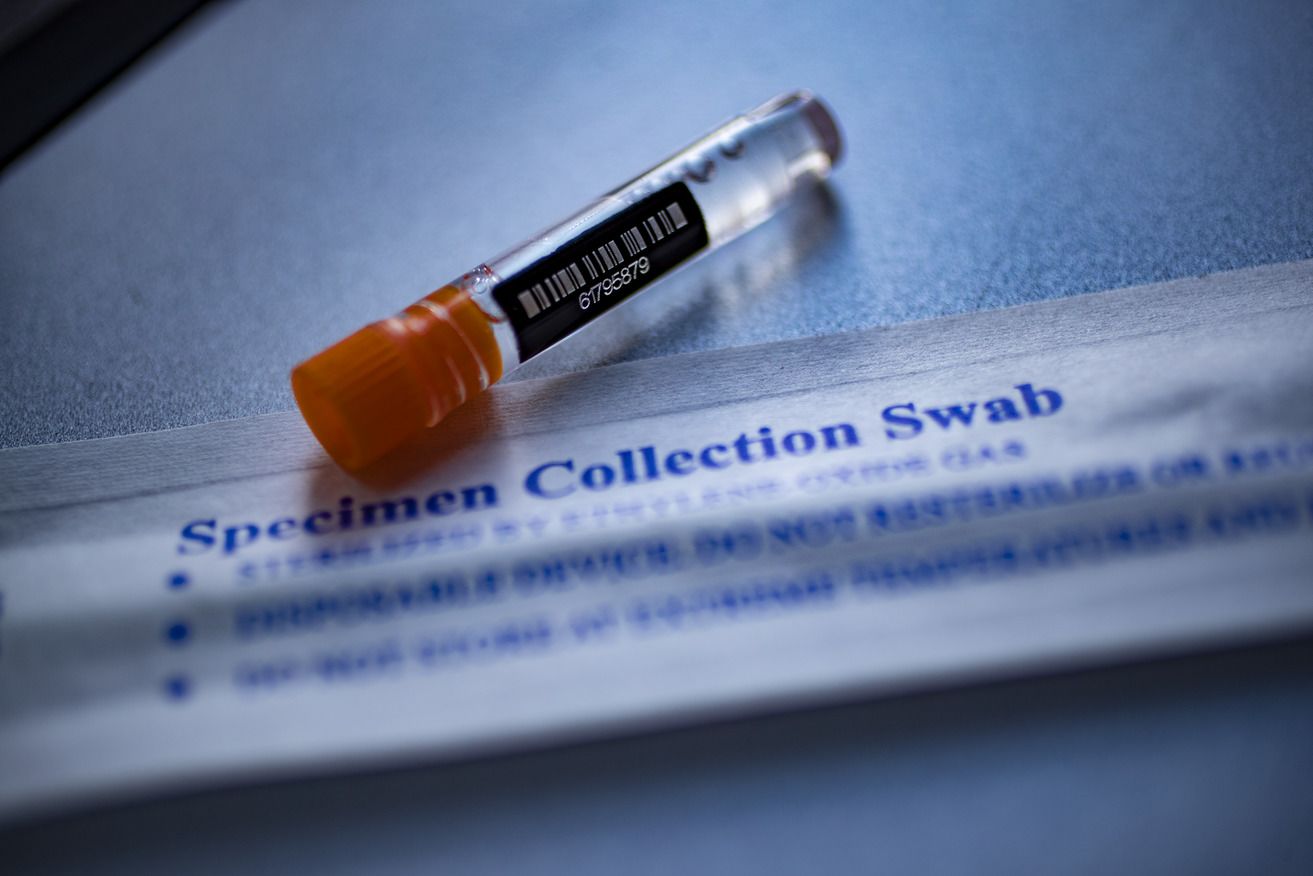

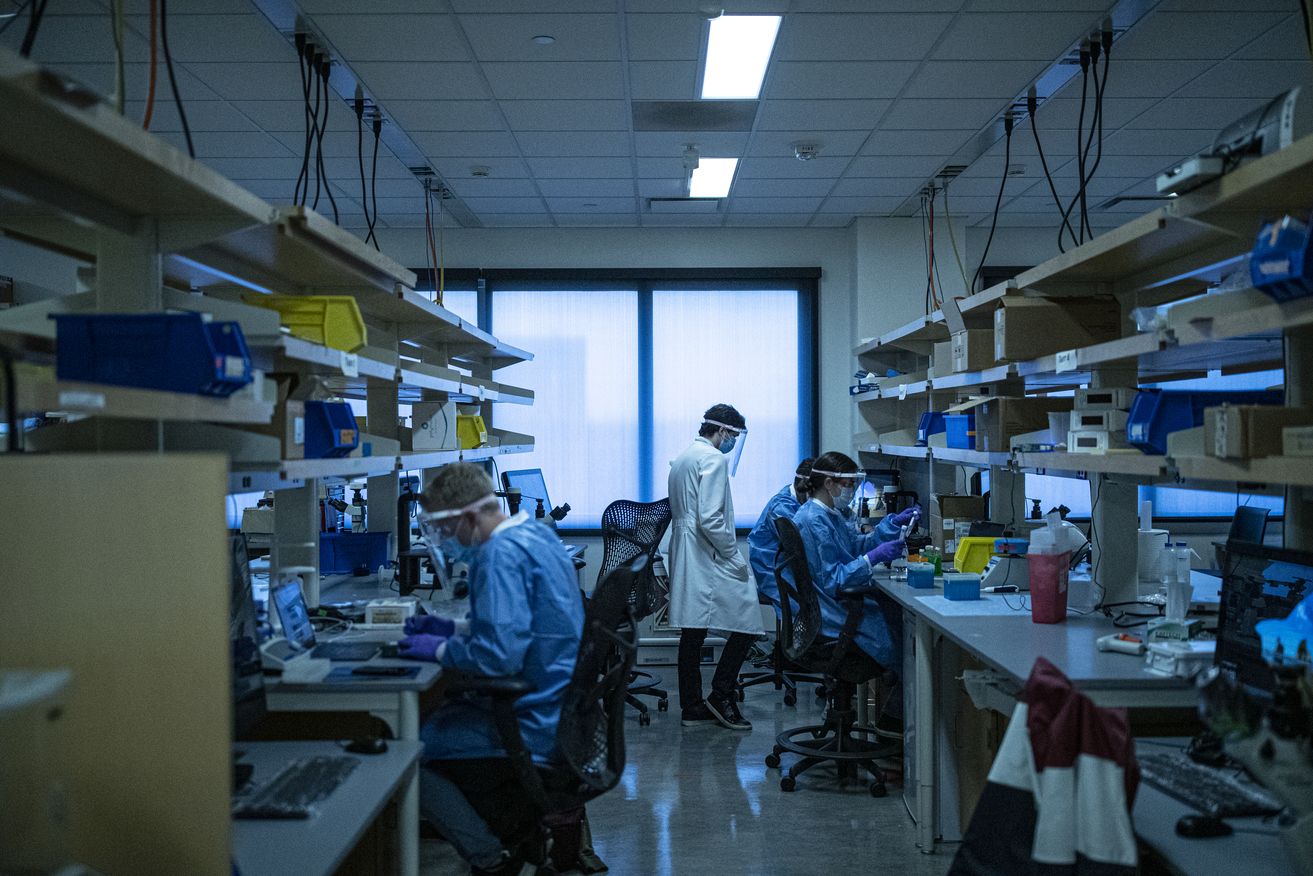

Temple's in-house COVID-19 testing program also featured the university’s own specially developed testing kits and a designated lab for test screenings. (Photography by Joseph V. Labolito)

Temple's in-house COVID-19 testing program also featured the university’s own specially developed testing kits and a designated lab for test screenings. (Photography by Joseph V. Labolito)

A location reimagined

“A few years back, a mumps outbreak on campus gave us the experience we needed and the confidence to know we could handle distributing this vaccine,” explained Virginia McNally, a registered nurse with Student and Employee Health Services who also volunteered at the Liacouras Center Surge Facility during the first months of the pandemic.

At each clinic, the team followed a strict workflow, with nurses reconstituting the vaccine and noting the expiration times. An area was designated for administering the vaccines and a space was set aside to observe the patients following the injection. Staff from Temple’s Office of Environmental Health and Radiation Safety took responsibility for managing storage, temperature control and expiration times of the vaccine.

Wearing color coded vests to indicate each one’s role, employees and volunteers—many of whom were students—from across the university, including School of Pharmacy faculty, all came together with one goal in mind.

It was all very precise and efficient. And it went like clockwork, because it had to.

“The comradery of the team and the way we all came together from different departments was amazing,” McNally noted.

“But when I looked around in White Hall at the line of chairs filled with people getting injections, it was not lost on me that this was not the intended purpose for the building,” she added. “And that’s when the historic importance of what we were experiencing would sink in.”

Ben Mobo, a physician and director of employee health services at Temple, also sings the praises of the volunteer crew and staff who manned the vaccine clinic, where he served as the lead medical officer on duty.

Mobo remained working in person on campus, starting with the earliest days of the pandemic, ensuring employee health workers were fit-tested—or properly fitted—with N95 masks and serving the facilities, maintenance and campus safety services staff members as they carried out their essential duties, also in person. Mobo made sure that health and safety protocols were being maintained and stayed up to date on how to keep workers safe and prevent workplace transmissions of the virus.

And, when an employee cut himself on campus during the process of 3D-printing face guards, it was Mobo who treated him.

“When he explained to me how he got his injury, I welled up with pride knowing Temple faculty and staff had undertaken that effort, literally making masks from scratch to protect our healthcare workers at Temple Hospital—it was amazing,” said Mobo.

“The comradery of the team and the way we all came together from different departments was amazing.”

A precious ingredient

Looking at how smoothly Temple’s vaccine clinics ran belies the logistics that went into pulling them together behind the scenes.

“In the beginning, if you recall, the vaccine was like gold,” said Mark Denys, senior director of health services at Temple.

The first hurdle for Temple was getting approved as a vaccination site by the city, Denys explained. Temple was the only university in the city that had its own vaccination site. Other universities had to partner with outside pharmacies or agencies to give their vaccines.

But what came with that approval was a host of requirements. As an approved site, the university had to ensure that only those meeting the criteria set by the city were, in fact, getting the doses. Those receiving the vaccines had to be Philadelphia residents, and they had to meet certain criteria, whether it was working in a high-risk setting or having specific medical conditions. And all of that had to be documented so that the people who needed the vaccine the most could be prioritized. As a result, the Temple team did a lot of vetting of lists, so that they could be sure not to violate any agreement the university had with the city.

“And then, of course, we used the Pfizer vaccine,” explained Denys. “So, in addition to requiring proper refrigeration, it also was complicated by being packaged in vials of six. We didn’t want to waste anything, so it was kind of a crazy time trying to make sure that we scheduled the appointments in exact multiples of six.”

During the peak weeks of distribution, the team was able to administer approximately 600 doses per day on average—with the count on a few of the days reaching a full 800.

But to really put Temple’s vaccine efforts into perspective, you need to understand that it was all happening simultaneously to an intensive and robust, in-house COVID-19 testing program.

A dose of ingenuity

When the spring semester began in January 2021, it saw the introduction of the first doses of COVID-19 vaccines on campus. And, the new year also witnessed something else—the launch of Temple’s own, in-house COVID-19 testing program: including multiple testing sites, the university’s own specially developed testing kits and process, and a designated lab where tests were screened.

The result of months of work, the program was a universitywide collaboration involving dozens of members of Temple’s community, from the Lewis Katz School of Medicine to Student and Employee Health Services and Information Technology Services.

Back in March 2020, the university’s initial plan had been to use “off-the-shelf” test kits and technology made by Thermo Fisher Scientific, a leading science and technology firm. But COVID-19 testing materials were in such high demand the company couldn’t keep up.

So, Temple turned to another biotechnology company … until a large shipment of test kits was delayed in Alaska for more than 10 days, that is. The shipment thawed and the contents were ruined.

“That’s when we decided that we were going to develop our own assay [the term used for the process of determining a COVID-19 test result] using off-the-shelf reagents [supplies needed for the test] ourselves,” said Glenn Gerhard, chair of the Department of Medical Genetics and Molecular Biochemistry at the Katz School of Medicine and head of the university’s COVID-19 testing lab.

Creating its own in-house testing program was a game-changer for the university; it used generic equipment and reagents that could be purchased more easily and at a lower cost.

“Instead of buying a brand name test, you go generic and make your own. The sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus had been published and there were several different assays around the world. So we used those as a guide to develop our own in-house protocol,” he added.

Because of the supply chain issues the team faced, they had to make sure they had a primary supplier and a back-up supplier for every item they needed, and took into consideration the item’s availability and shipping time.

For example, in March 2020, only two companies in the U.S. were making the plastic swabs necessary for test kits and they ran out, prompting Temple to switch to custom-designing and manufacturing the swabs in China.

Swab tubes were in high demand as well. Gerhard and his team sourced smaller tubes, figured out how to scale them for high-volume use and developed a workaround so they would mesh with the robots used in the lab.

According to Gerhard, implementing a branded, commercially available testing program similar to the one Temple developed would have cost around $15 million. Building the program in-house was a challenge, but it was also more cost-effective in the long run.

“You have to do more and use your own ingenuity and work on it, but that still doesn’t come anywhere near the cost of what you pay when you buy off the shelf,” he said.

"The sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus had been published and there were several different assays around the world. So we used those as a guide to develop our own in-house protocol."

A spoonful of collaboration

While Gerhard and his team created the testing kits and lab process, Denys and Meghan Duffy, associate director in the office of the provost, worked on the testing sites. “We really looked to see where we needed the tests and what sites and locations would fit our needs, which was basically a large open space that could get people in and out very quickly and easily,” Denys said.

He and Duffy considered 20 different sites at the Health Sciences Center and on Main Campus, discussing possible staffing and capacity, looking at the number of people who would be on campus, and trying to predict the demand various locations would have to meet. Mitten Hall and the Howard Gittis Student Center were chosen because the former is often used for vaccinations and the latter is a familiar location for students. Also, both were easily accessible.

“It was a huge partnership with the ITS department, with facilities, with HR to get staff up and running, to get the spaces set up with power and data and equipment,” Duffy said. “It really was a universitywide initiative.”

The biggest challenge they faced was the lack of time. Temple’s testing lab didn’t exist at Thanksgiving of 2020 and had to be outfitted and staffed quickly, with Gerhard’s team expanding from three or four scientists and technicians to around a dozen. The testing sites also needed access to hard data because information covered by HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) can’t be transmitted using Wi-Fi.

Denys and Duffy worked through winter break, as did many of their colleagues, and hired 35 people in two weeks, some of whom were temporary employees that had to be replaced as they took up positions elsewhere.

“We had to train everybody in a very short period of time,” Denys said.

Another challenge was establishing the data flow between the testing sites, the lab and Student Health Services. “We already had an electronic medical record system,” Denys said. “But we had to get a person’s unique identification to the lab along with a lab order. Then, they had to be able to link the test vial up to the individual, get the result and make sure that it was assigned to that individual. It all has to be ironclad.” Student Health received a copy of the results, which they then shared with students.

The program was a monumental effort. “We have set up mass vaccination clinics and flu shot clinics and we did several mass testing days in the fall, but nothing to the scale of what we did in the spring,” Denys said.

Failure was not an option

Testing schedules for each student varied according to different categories, based on where the student lived and how many in-person classes they took. The testing process began when a student checked in at a testing site and received a vial with a barcode that was entered into Temple’s system. Each test was self-administered under observation, to ensure it was done correctly.

The COVID-19 test samples were collected with swabs. The student deposited the swab they used in the vial and it was taken to the testing lab, where Gerhard and his team sprayed it and other vials to decontaminate them. Next, the team recorded the barcode on each vial so that it could be matched to the barcode assigned to each student when they checked in. Then they began testing samples, using robots to extract RNA and adding reagents.

Temple’s testing process used RNA—a nucleic acid that helps control the synthesis of proteins—because a small amount of it can be copied over and over again, making the most of what’s available in the sample.

“You have to extract the virus RNA or protein out from the swab into the fluid and from the fluid into your own laboratory tube,” Gerhard explained.

“Some labs rely only on the machine to make calls. That is potentially dangerous,” Gerhard said. “You have to look. So I look, then I make the call and process the data into negatives and positives.”

The whole process took between eight and nine hours and the lab ran approximately 10,000 tests a week.

“The goal of testing isn’t to prevent an individual person from testing positive,” Denys said. Widespread community spread meant people were catching COVID-19. “But by testing this often and this many groups, the goal is to prevent or limit the chances of that positive individual causing a cluster of individuals or a cluster causing an outbreak,” he said.

As soon as a positive result was registered, the student received a secure message via the electronic medical record, followed by an email and a phone call from the contact tracing unit—which had doubled in size—or staff in Denys’ office.

“By testing this often and this many groups, the goal is to prevent or limit the chances of that positive individual causing a cluster of individuals or a cluster causing an outbreak.”

Keeping the lab running wasn’t easy. “The main challenge was getting the lab equipment, protocols, reagents and personnel in place in a compressed period of time to go live at the start of the semester, and then trying to keep ahead of the supply chain issues,” Gerhard said. “In addition, the scale of the operation was such that things that normally don’t happen very often with ‘normal' numbers of samples, happen much more frequently, from instruments breaking down to computer glitches.”

Everyone involved kept going because the program was essential. It was very important to identify people who had COVID-19 because so many people could be asymptomatic and could spread it without knowing it, Denys said. “It was really vital to getting more people on campus,” he said, “so that we could maintain more in-person classes, have more students living in the residence halls and start getting back to having a more vibrant campus community around.”

The program became the embodiment of Temple's motto, Perseverance Conquers. “Failure was not an option,” Denys said. “Saying no and giving up throughout this entire pandemic is just not something any of the people on the team would accept. You just figure out another way to get it done.”

Remembering John M. Daly

John M. Daly, MED ’73, the late dean of the Lewis Katz School of Medicine, was instrumental in establishing Temple’s testing program.

“He cleared whatever institutional obstacles were in the way and was a stalwart advocate and supporter,” said Glenn Gerhard, chair of the Department of Medical Genetics and Molecular Biochemistry at the Katz School of Medicine and head of the university’s COVID-19 testing lab. “Dean Daly was a frequent visitor to the lab, which showed my lab personnel just how important the work they were doing was to the university.”