All hands on deck

Owls pitched in to produce desperately needed PPE

When Temple University Hospital healthcare workers were faced with looming shortages of personal protective equipment during the early days of the pandemic, a group of Temple volunteers—spanning multiple disciplines—quickly coalesced to come to their aid.

One afternoon early in April 2020 stands out as particularly memorable for Jack Oswald, ENG ’20. The then fourth-year bioengineering major described how he carefully poured liquid plastic into a multicavity mold. The mold was being used to form 24 headbands that would become a critical part of face shields needed by front-line workers at Temple Hospital.

Then, said Oswald, he took a quick 10-minute break—to present his senior design capstone project via Zoom to his classmates and professor.

And, when that wrapped up, he went back to the mold, pulling his casts out and filling them up again.

“It was a little scary, given that there were so many unknowns about the pandemic,” said Oswald, reflecting on that day. “But I would have done anything to use my engineering skills to help out our hospital workers. That was my motivation and the motivation of everyone else.”

During early days of the global health crisis in Philadelphia, the number of coronavirus inpatients at Temple Hospital was rapidly rising.

It jumped from an average of 78 per day in March 2020 to 156 in April—the highest COVID-19 patient load at the time in the entire Philadelphia region—and it prompted the hospital to convert its Boyer Pavilion to a COVID-19 facility.

As a result, like other healthcare facilities locally and nationwide, the hospital was rapidly running low on personal protective equipment (PPE). “Nurses who treat patients with infectious diseases are used to going back and forth between patient rooms and throwing out their PPE in between patients to maintain a sterile environment,” explained Michael Kala`i, senior director of technology, facilities and operations in the College of Engineering. “If a nurse checks each patient seven times a shift, that’s 70 shields, N95 face masks, pairs of gloves and gowns.”

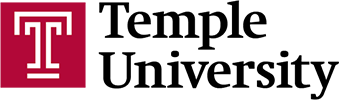

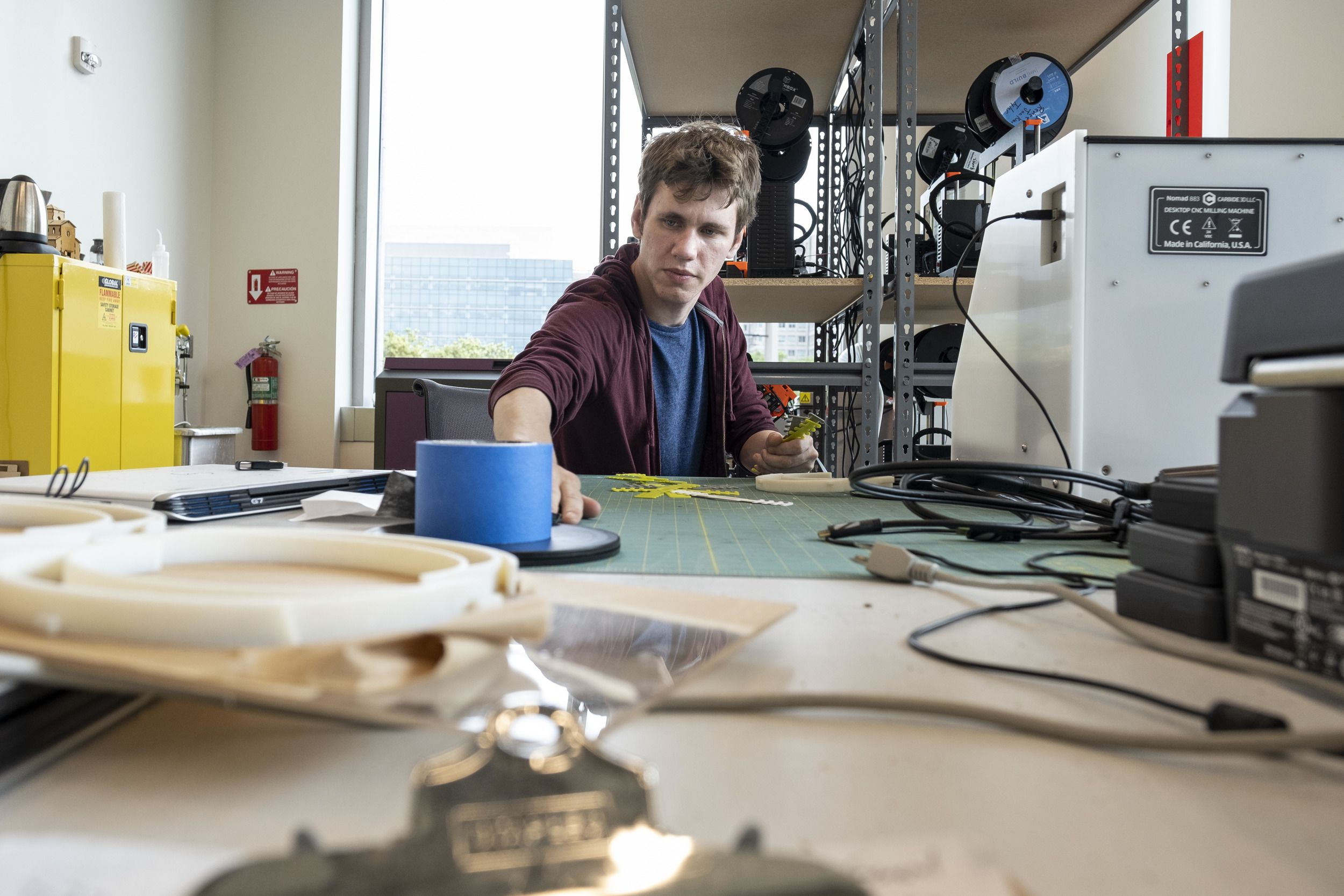

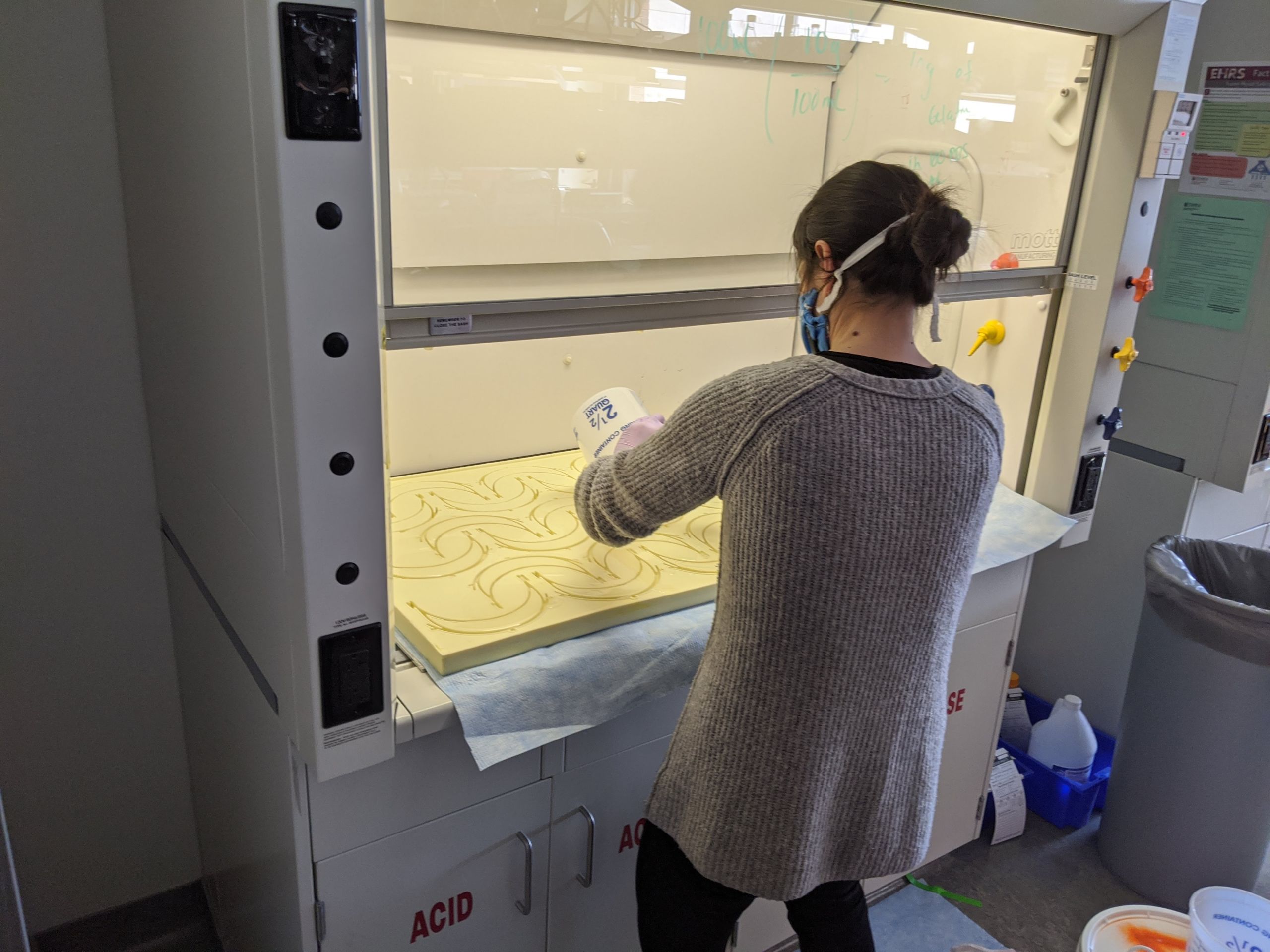

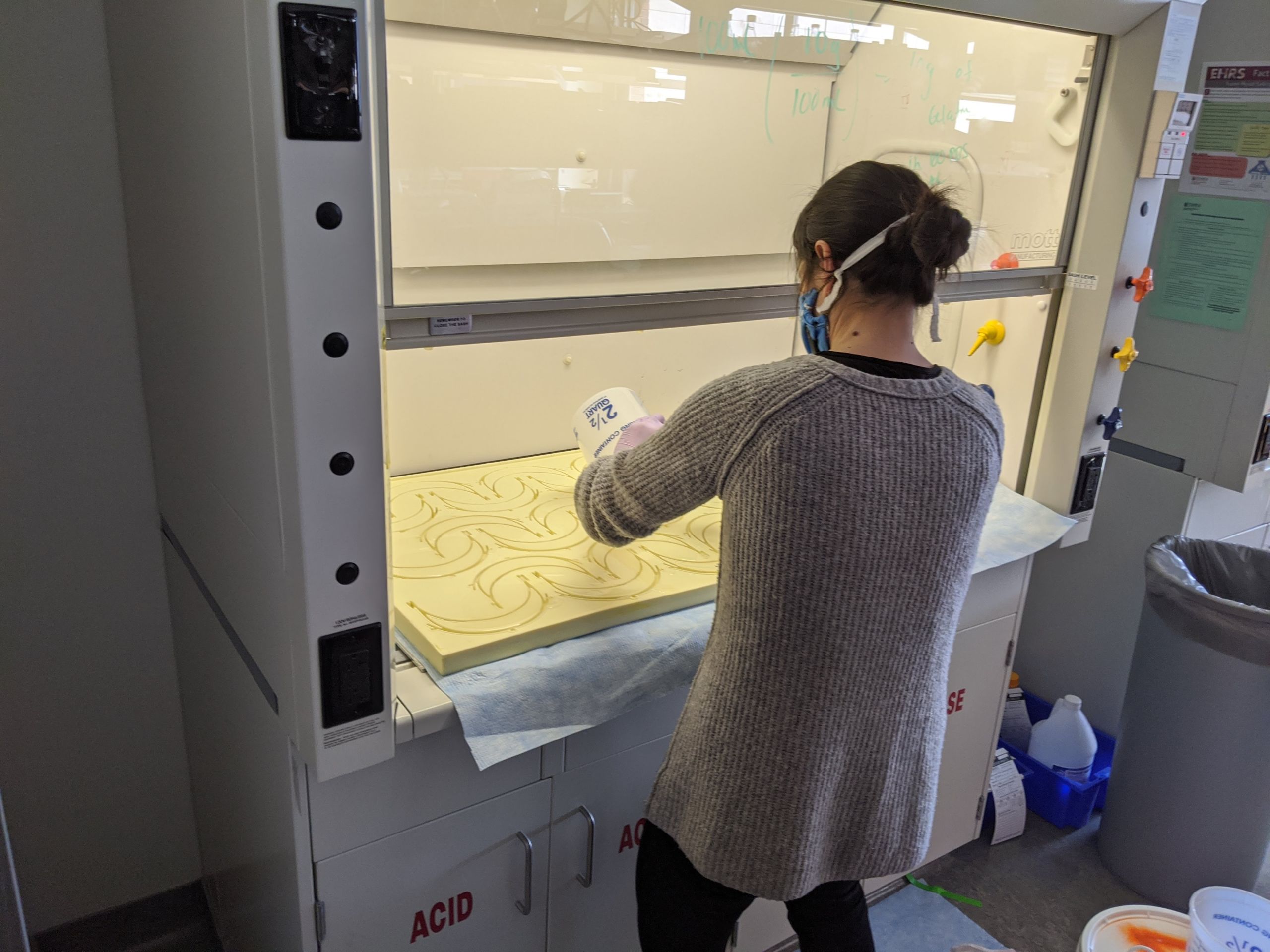

A student in a classroom lab assists in creating personal protective equipment (PPE).

A student in a classroom lab assists in creating personal protective equipment (PPE).

Michael Kala`i, senior director of technology, facilities and operations in the College of Engineering, assembles a face shield.

Michael Kala`i, senior director of technology, facilities and operations in the College of Engineering, assembles a face shield.

Two students wearing face shields work on preparing PPE.

Two students wearing face shields work on preparing PPE.

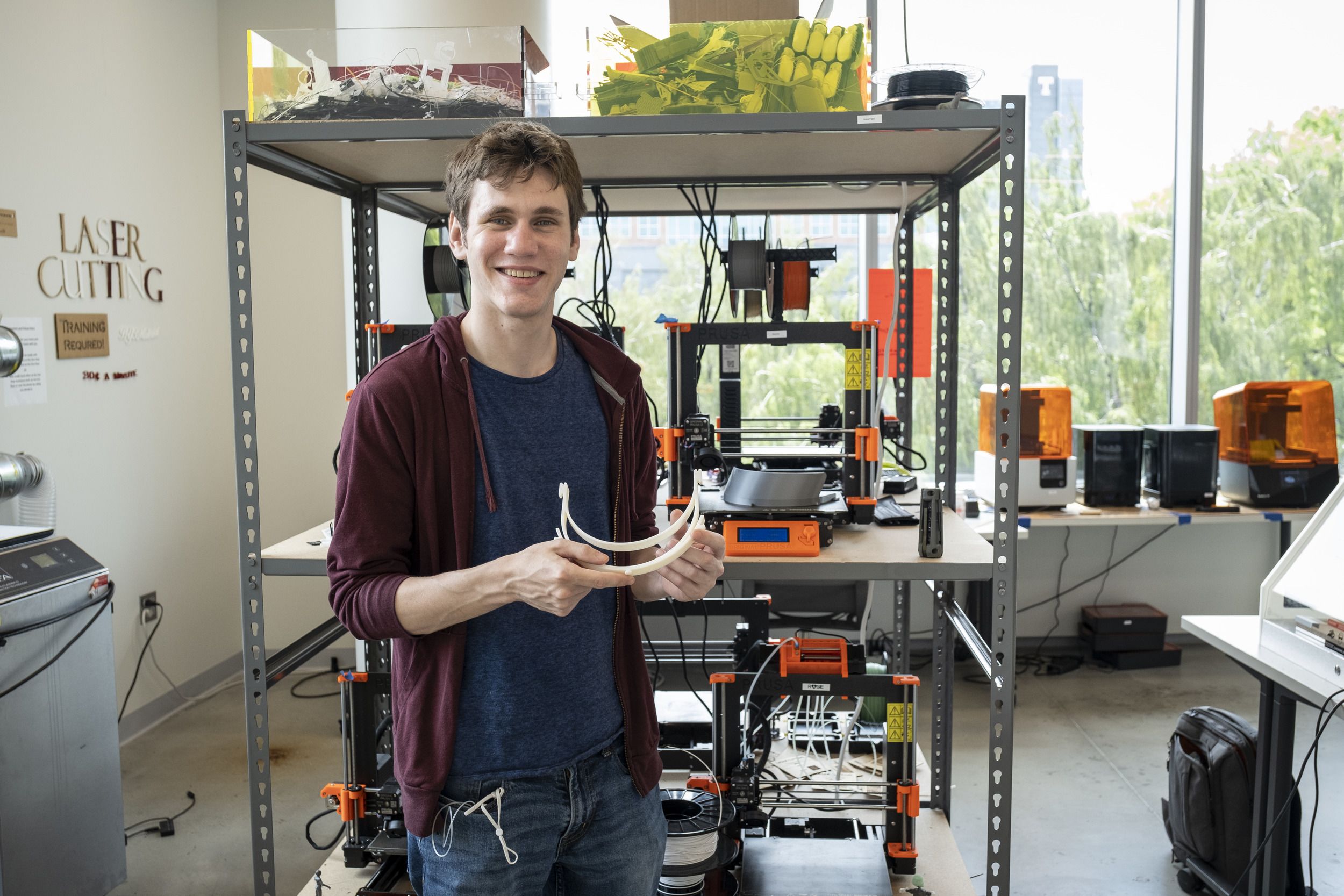

David Ross, manager of Charles Library’s makerspace, sits at a 3D Printer.

David Ross, manager of Charles Library’s makerspace, sits at a 3D Printer.

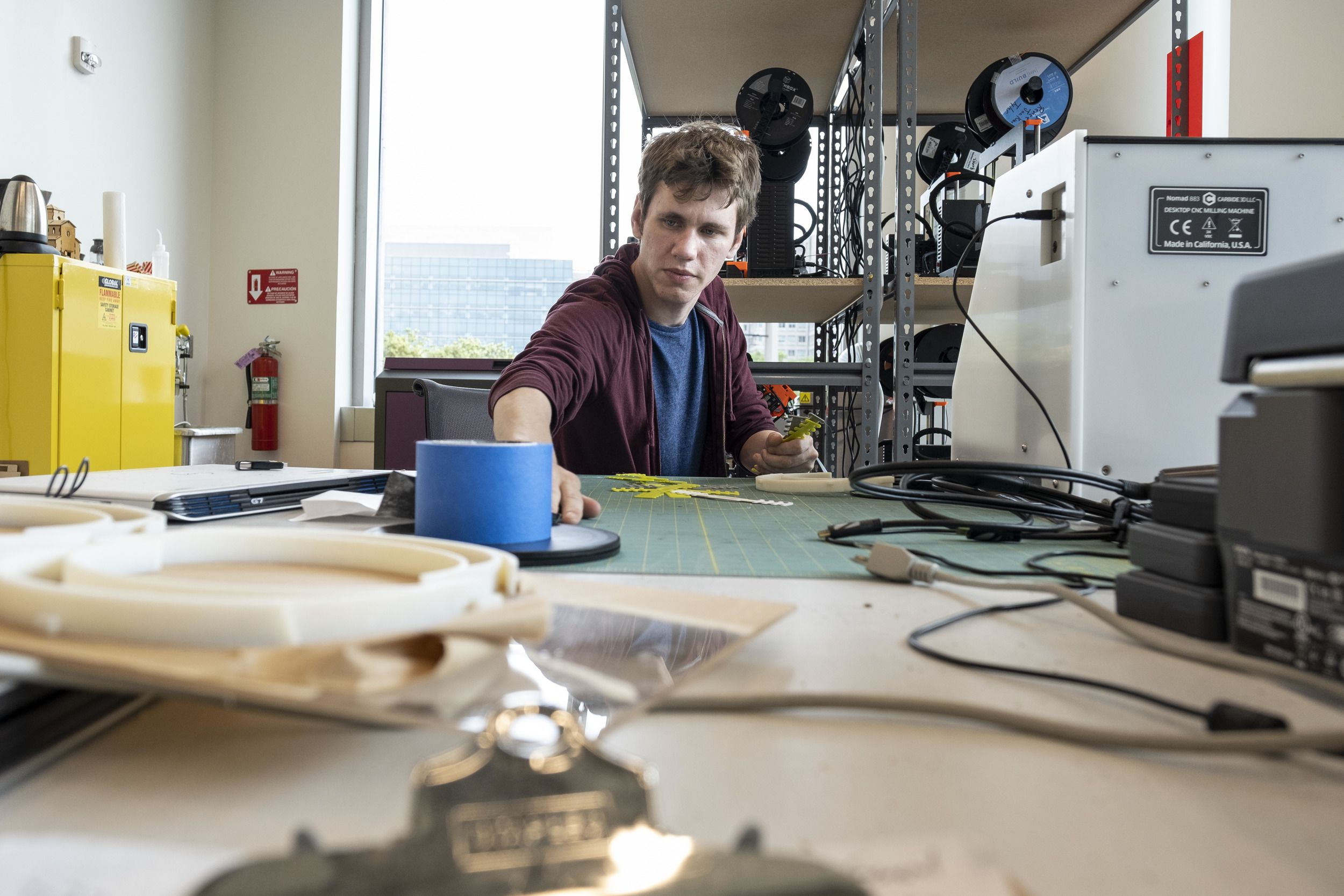

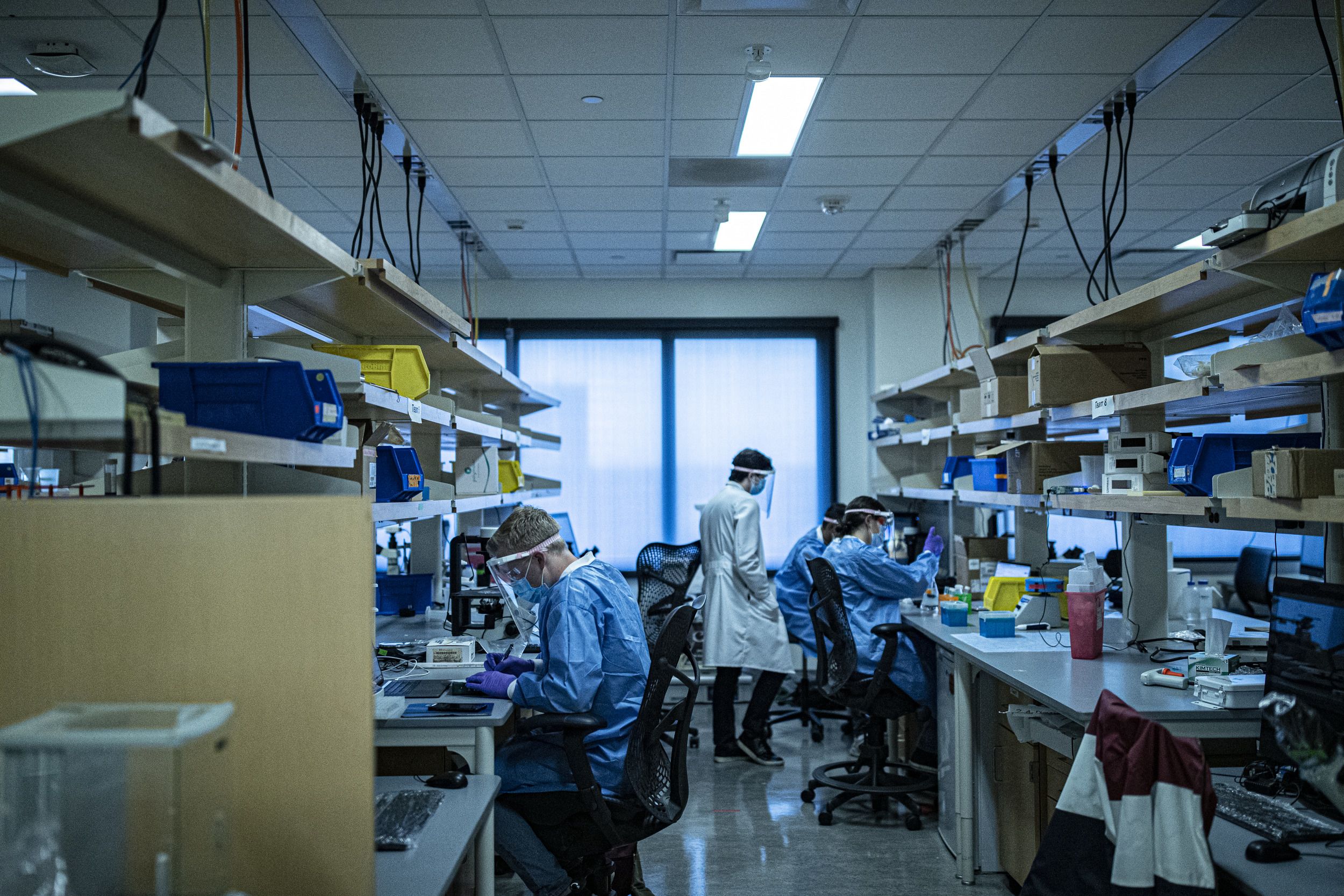

Students wearing PPE work together in a lab.

Students wearing PPE work together in a lab.

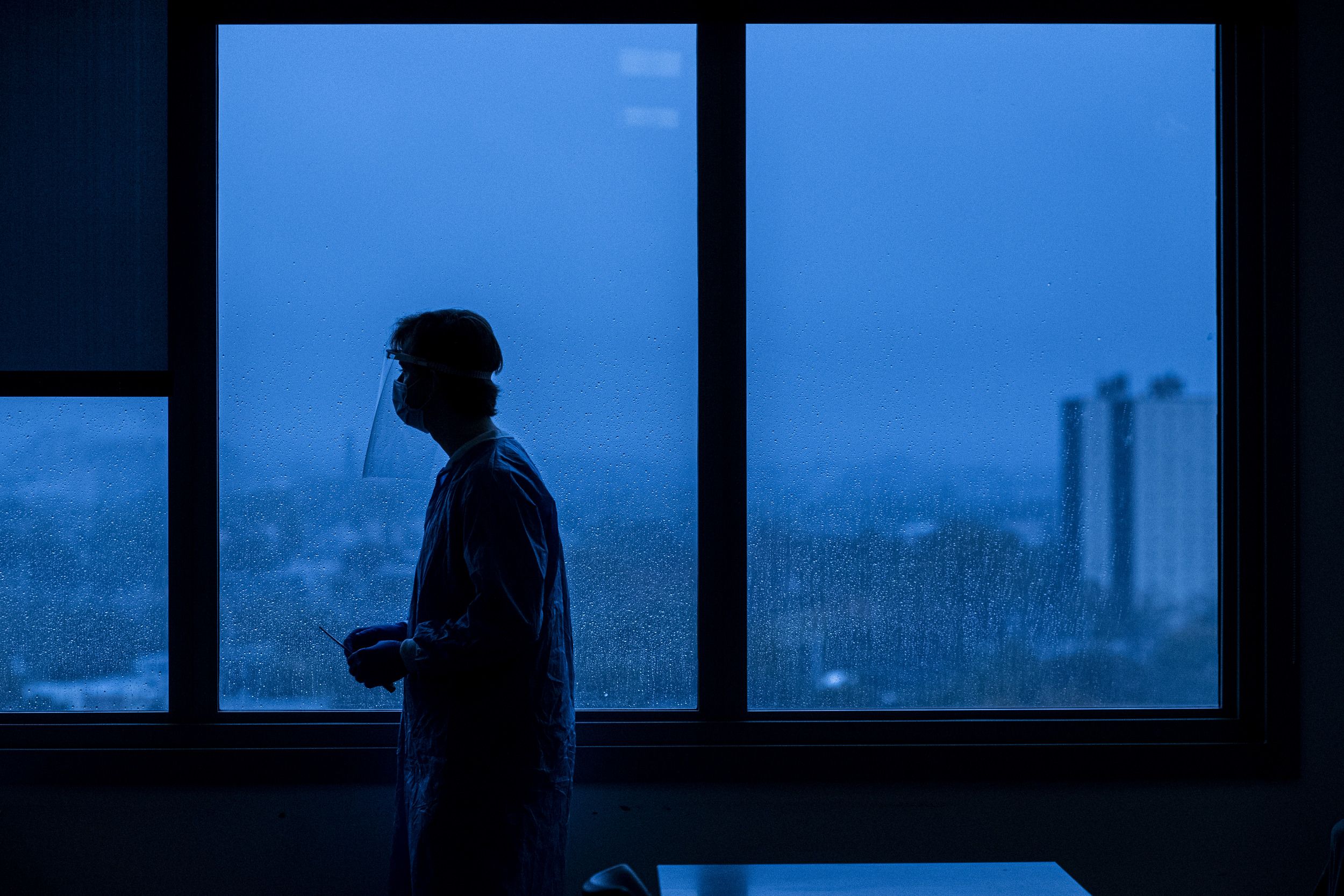

A student worker takes a break in the lab.

A student worker takes a break in the lab.

Within days of hearing about the PPE scarcity, faculty, staff and students from several different like-minded initiatives across campus unified to address the shortages.

“It was a World War II, all-hands-on-deck kind of effort,” recalled Kala`i, who spearheaded the universitywide enterprise. “We were putting in 12- to 14-hour days.”

In all, five dozen people working in a group that became the Temple University COVID-19 Assistance Team swiftly came together from a range of departments to launch an ad hoc manufacturing effort to produce face shields that could be worn for a full eight-hour shift.

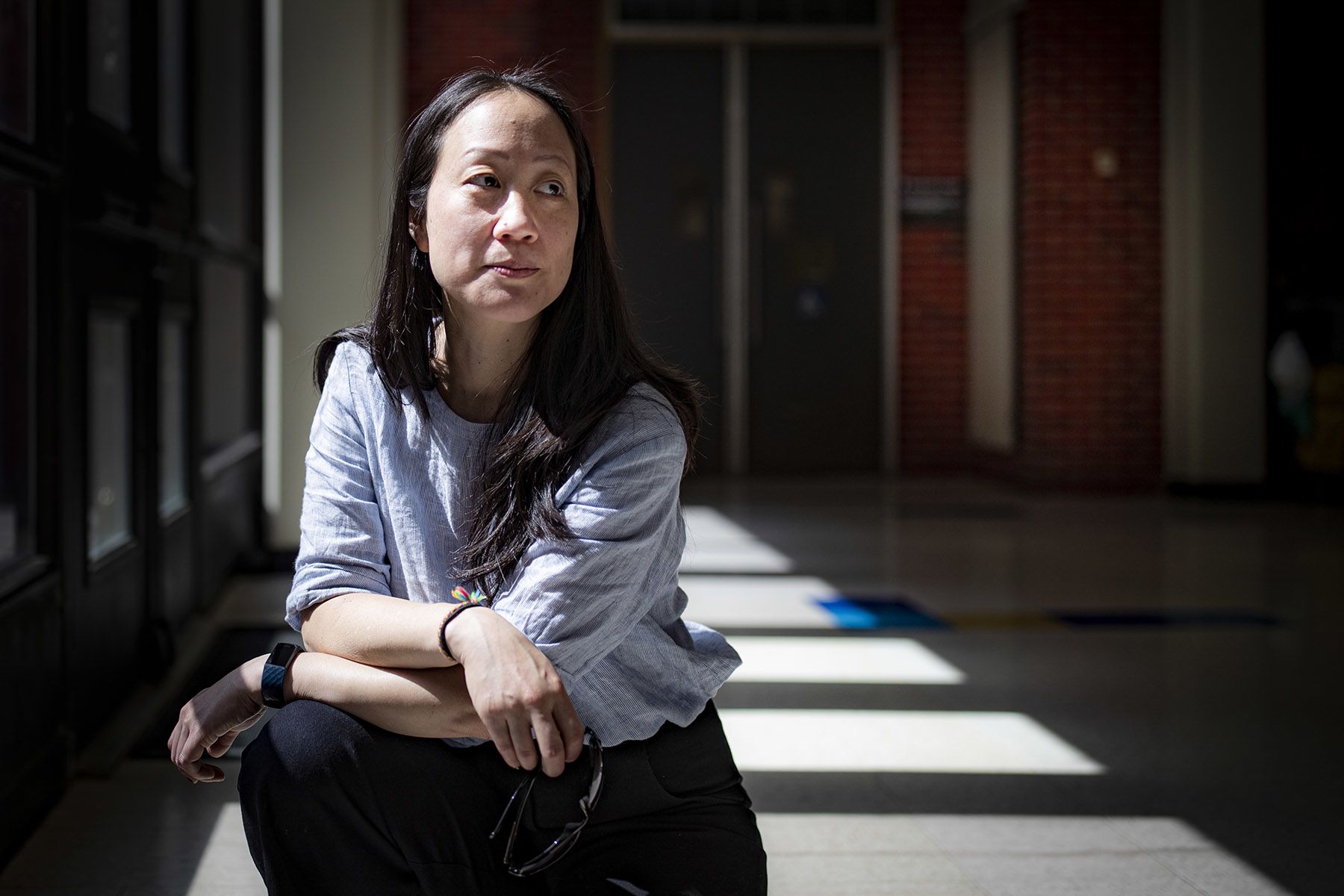

“The idea was to make it something that could be built fast, and to have it be sterilizable and reusable,” explained Tonia Hsieh, an associate professor of biology specializing in biomechanics.

The team included Temple faculty members, employees and students hailing from the College of Engineering, College of Science and Technology, Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple Libraries, Temple Health and the Office of the Vice President for Research, among other areas. Their expertise spanned administration, research, materials fabrication, 3D printing, healthcare, emergency medical services and basic science. Many worked remotely—and, in some cases, wore PPE themselves and practiced physically distancing—to avoid further spread of the coronavirus.

Ultimately, over the course of six weeks, the team produced more than 16,000 face shields.

“The face shields are excellent. Everyone who has used one, including me, has found them to be a great improvement over reusing the single-use face shields that we have had access to,” Professor of Anesthesiology Scott Schartel wrote in a thank-you email to Kala`i in mid-April 2020. “The ability to clean and decontaminate them and continue to use them is outstanding.”

“The shields will help to protect us as we care for all of the patients. The shields also represent the way we will get through this battle, by coming together as a community to fight the virus.”

Nuts and bolts and 3D Printers

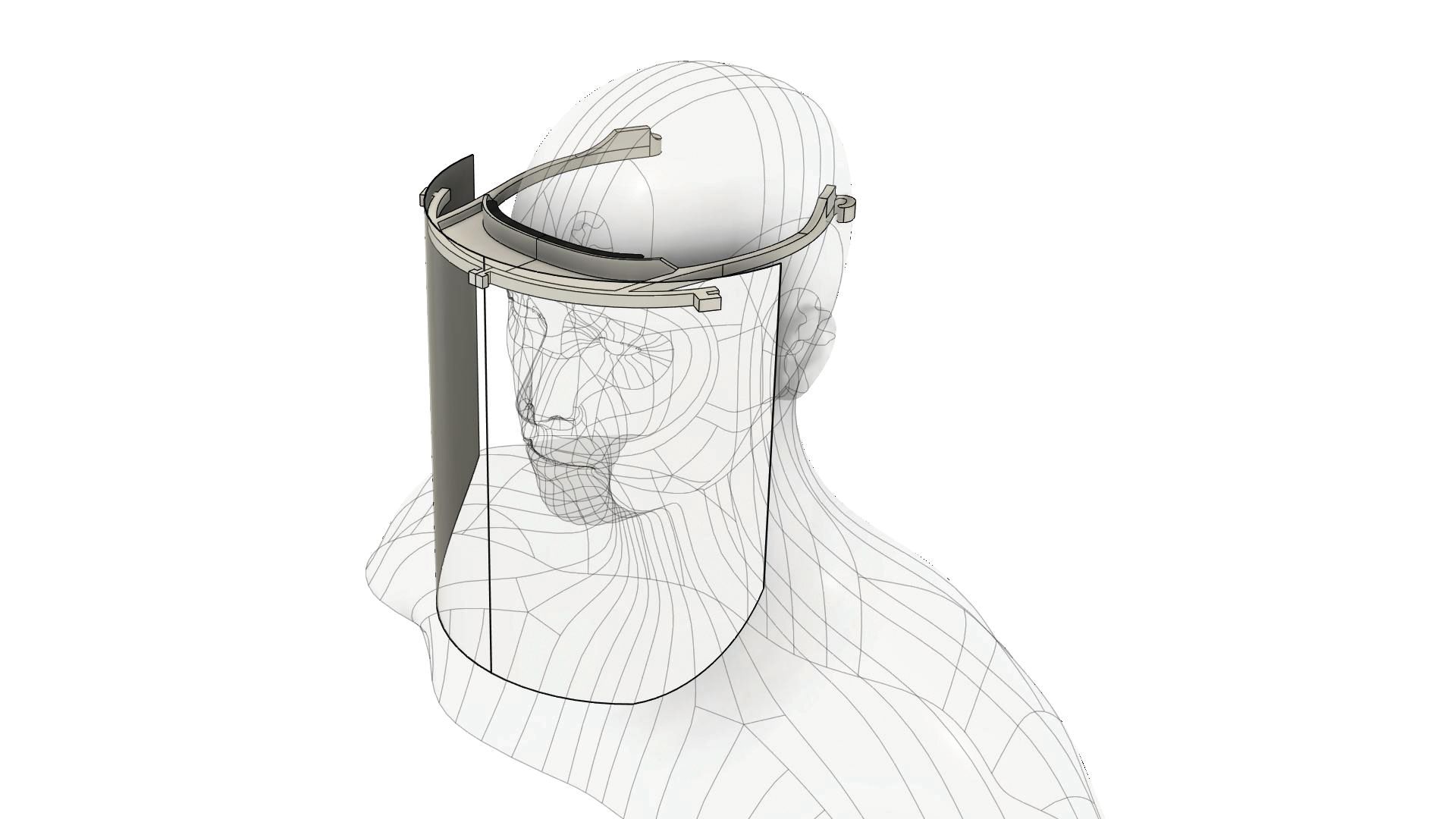

Hsieh, who led the production and design of some of the face shields, contributed her particular expertise: research that includes casting molds of lizard feet to better understand how they negotiate walking on disparate surfaces. Bill Wohl, a transplant coordinator for Temple University Hospital, brought to the project his experience as a first responder and knowledge of 3D printing and construction. Together the team considered several prototypes, including one headband produced with 3D printers and one made from a 3D-prototype foam mold.

3D-printing the headbands initially seemed to be the most promising way to go. However, using the 3D printers to directly make the headbands proved problematic for several reasons. Such materials have micro-ridges and pores that cannot quickly be sterilized; certain plastics don’t mix well with alcohol-based sterilizers; and applying epoxy to smooth the surfaces was more costly, more time consuming and—even if the headbands were produced under ventilated hoods—could potentially be hazardous to those applying the epoxy.

In the end, the team used a 3D printer to create the headband prototypes and a Computer Numerical Control Machine (CNC) to create the headbands.

David Ross, the manager of Charles Library’s makerspace, was often the only person in the library available to 3D-print the original prototype molds for the face shield headbands.

“It was super stressful but, at the same time, totally worth it,” said Ross. “It’s amazing how we cranked out designs as fast as we did.”

A CNC processes materials to meet specifications by following a coded programmed set of instructions without an operator manually controlling it. Using one was the brainchild of Tyler faculty members Tim Rusterholz and Andrew Witt.

“I brought them on board after presenting them with what sounded like a crazy pie-in-the-sky challenge of 100 headbands every 15 minutes,” said Hsieh. “And they were like, ‘Yup, we can do that.’”

Using carved foam molds to create headbands for face shields.

Using carved foam molds to create headbands for face shields.

Cutting plastic sheets for use in face shields.

Cutting plastic sheets for use in face shields.

A completed face shield sits on a worktop.

A completed face shield sits on a worktop.

After the headbands were carved in foam, the headbands were then poured, cured, demolded, cleaned, sanded and deburred at both the College of Engineering and the Tyler School of Art and Architecture.

Meanwhile, massive sheets of clear plastic were cut and three-hole punched to form the face shields. “At the College of Engineering, in just one hour we were pouring as many as 60 to 100 headbands and cutting as many as 700 face shields,” said Kala`i.

Many 3D printers were running simultaneously from across multiple campus locations to produce a small clip that allowed users to adjust the black elastic headbands of the face shields.

Then, all the parts—the front headbands, the face shields and black elastic headbands—were assembled and packed for delivery at both the College of Engineering and the Conshohocken facilities of TDI Technologies, Inc.—whose affiliated nonprofit, ChariTdi, enlisted the help of 40 more volunteers, including Temple alumni and students.

Covering all the bases

As the team continued to produce the shields, they worked directly with the product’s end-users, such as doctors, to gather feedback and make adjustments to better fabricate the face shields.

For example, the first NIH-recommended designs the team tried had openings at the top and face shields that reached just slightly below the chin. With direct input from healthcare professionals, who said they needed to be protected when they looked both upwards and downwards, laser-cut foam inserts were used to fill in the top holes and the face shields were lengthened to protect more of the neck.

In addition to producing the face shields, the group also lent their expertise to the hospital staff in other ways. They organized a ventilator control team that extended links from patients’ ventilators to computer monitors and keyboards outside the patients’ rooms so they could be adjusted by the medical staff without donning PPE, and they helped hospital personnel find parts for other pieces of equipment as needs arose.

The task force also made sure that their designs and processes were available for anyone else in the public who wanted to make their own face shields. In fact, undergraduate engineering students led a series of virtual build sessions to share with Philadelphia’s maker community how to 3D-print and produce protective equipment based on designs created or adapted by the task force.

As well, before the national supply chain caught up with demand, the group had planned to prototype and eventually produce other critical hospital supplies, including NIH-approved respirator masks, simple ventilators and replacement ventilator parts.

“The faculty, nurses and doctors

all love the face shields.”

Going the extra mile

Today, Oswald is working on vaccine research and development as a sample management scientist at Eurofins Lancaster Laboratories in Lansdale, Pennsylvania. “Being part of this huge effort at Temple to keep people safe so they could do their jobs and care for others while we waited for vaccines was incredible,” he reflected.

The same goes for Reid Overturf, the assistant director of information technology services at Temple’s Ambler Campus. Besides making sure everyone at Temple Ambler had remote access to the technology they needed to carry out their responsibilities, Overturf also helped the team’s effort.

“Before we knew coronavirus transmission had little to do with surface contact, it was a scary and nervous time,” he recalled. “Being out in the real world early in the pandemic meant we were all very careful about following all the protocols to stay safe for one another.”

One Saturday morning when the crew was short-handed, Overturf was planning on driving to Main Campus to lend a hand. But then the longtime Temple employee read an email indicating that a roommate of one of the College of Engineering volunteers had tested positive for COVID-19. Kala`i told Overturf, who is 62, to stay home.

So, the Wyndmoor resident decided to pitch in another way. He subsequently became the group’s de facto delivery person, single-handedly making about five trips to a supplier in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to pick up and then drop off large quantities of the resin and other materials that were needed to make the face shields on Main Campus.

"It was incredibly meaningful that our professional colleagues and friends on Main Campus stepped up to really do everything they could to support and help all of the folks working in the hospital.”

For many on the task force, the fight against COVID-19 was personal. Hsieh was one of them.

“My sister works at a hospital in New York City, so when the pandemic exploded there, I was feeling helpless. Here I was in the midst of this enormous outbreak with all this training behind me and all this intellectual power, feeling totally helpless,” Hsieh said. “She said they needed N95 masks and ventilators … and I thought, ‘I can’t get you a ventilator, but I know enough about building things and engineering things that I can probably build something [similar to] an N95.’”

Jason Fowler, the fabrication facilities coordinator for the Tyler School of Art and Architecture’s Department of Architecture, was another of the team’s leaders. “Everything impressed me about this project—the students’ knowledge, ability, their problem-solving skills; the upper-level leads like Mike Kala`i and Bill Wohl, who were steering this project; and the rest of us who worked equally hard and selflessly to do something that was really good,” he reflected.

“I've worked on some large projects in the past as a production artist, some on a national level, but this was easily the most meaningful because of the purpose it served, to just help keep people safe so they could provide the care so desperately needed.”

Added Kala`i: “To have people you don’t know putting in extra hours for no extra pay and even sometimes skipping meals while they put their heart and soul into trying to help people they didn’t know was a completely moving experience.”

Hsieh agreed. “I’m very encouraged that there was such a community of people at Temple who were willing to put their lives on hold to come together to combine our very disparate expertise in a very collaborative, innovative and interdisciplinary way. It was miraculous to see it come together so quickly and effectively.

“I’m also eternally grateful to all the doctors, nurses and support staff who have been working on the front lines, and I’m grateful that we had this opportunity to do our small part to help them and try to keep them safe while they tried to save lives.”

Cheers for this pharmacy professor

Early in the pandemic, David Lebo watched a news report about distilleries converting from producing whiskey and other spirits to hand sanitizer amid a nationwide shortage.

“We could do that,” the professor of pharmaceutical sciences and director of Current Good Manufacturing Processes (cGMP) at Temple University’s School of Pharmacy, said to himself.

“Things were really difficult at the hospital, and it was very personal for me.”

Normally, the cGMP lab—one of only six associated with a school of pharmacy in the nation—supports and ensures the expert production and packaging of clinical supplies and the manufacture of high-quality treatments and placebos.

But, in late March 2020, to combat the coronavirus pandemic, Lebo and his assistant Justine Williams used a formula published by the World Health Organization to begin producing hand sanitizer and placing it in sterile spray bottles for use at Temple University Hospital and the Kornberg School of Dentistry.

Until commercial supplies became more readily available last summer, they produced between 500 to 600 liters of sanitizer. Lebo also donated sanitizer to St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, where his late wife worked, and the Bethesda Project’s two Philadelphia homeless shelters.

“Things were really difficult at the hospital, and it was very personal for me,” explained Lebo. He was particularly thinking of two front-line professionals: Gerard Criner, chair and professor of thoracic medicine and surgery at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine and director of the Temple Lung Center, who led the hospital’s COVID-19 response; and Nur Kazazz, PHR ’14, a clinical pharmacy specialist at the hospital who focuses on lung patients.

“Dr. Criner has been a big supporter of mine throughout my research working on multiple clinical trials, and Nur is a former student who’s like a daughter to me,” said Lebo. “I couldn’t bear the thought of them risking their lives facing patients without having some protection.”

Uniting with purpose

During this grave period of uncertainty, the strength and the spirit of Owls shined through. Front-line healthcare providers worked around the clock, while faculty and staff showed the creativity, drive and grit that define Owls, nimbly pivoting to virtual modes of instruction and enabling the university to continue to fulfill its educational mission.

And the entire Temple family pitched in to help.

In the months following the crisis, Temple was one of the first institutions to distribute funds it received via the CARES Act, sending more than $14.5 million directly to students. Then in March 2021, as part of the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRSSA) Act, the university disbursed roughly the same amount to 16,201 students who were enrolled for the spring 2021 semester—including those pursuing undergraduate, graduate and professional degrees—through the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF) II.

Giving to the university skyrocketed, as well. Overall donations to Temple in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2020, totaled $108 million—more than $9 million above the previous record. Here are just a few highlights from an unprecedented year.

- Owls contributed more than $140,000 to the Student Emergency Aid Fund, which helped students pay for such immediate necessities as rent, groceries and internet access.

- In just a few months, donors responded to a special fundraising campaign to support the urgent needs of both Temple’s front-line workers and neighbors by contributing over $1.13 million—along with countless gifts of masks, shields, gloves, meals and other items.

- Fundraising initiatives for Temple University Hospital and the Lewis Katz School of Medicine raised more than $3 million to combat COVID-19 and support the North Philadelphia community.

- Temple Toast, the university’s annual day of giving, in April 2020 focused entirely on supporting students and front-line responders. More than $518,000 was raised in 24 hours—including $56,000 in support of three emergent needs initiatives at the university: the production of hand sanitizer at the School of Pharmacy, the distribution of personal protective equipment at the School of Podiatry, and the manufacture of face shields by the Temple University COVID-19 Assistance Team. In all, the 2020 Day of Giving totals beat the 2019 amount by nearly $40,000.

And the giving has continued throughout the course of the pandemic. In the current fiscal year, donors have nearly matched last year's record Temple Toast giving with another $463,292; gave $223,313 during Giving Tuesday on Nov. 29, 2020, which included support for students; and, as of mid-May 2021, have contributed another $90,554 to the Student Emergency Aid Fund.