Our finest hour

Staying on the sidelines was never an option

How Temple staff, faculty and students rallied

to build a working COVID-19 hospital

for sick Philadelphians from scratch

on a gym floor—in two weeks.

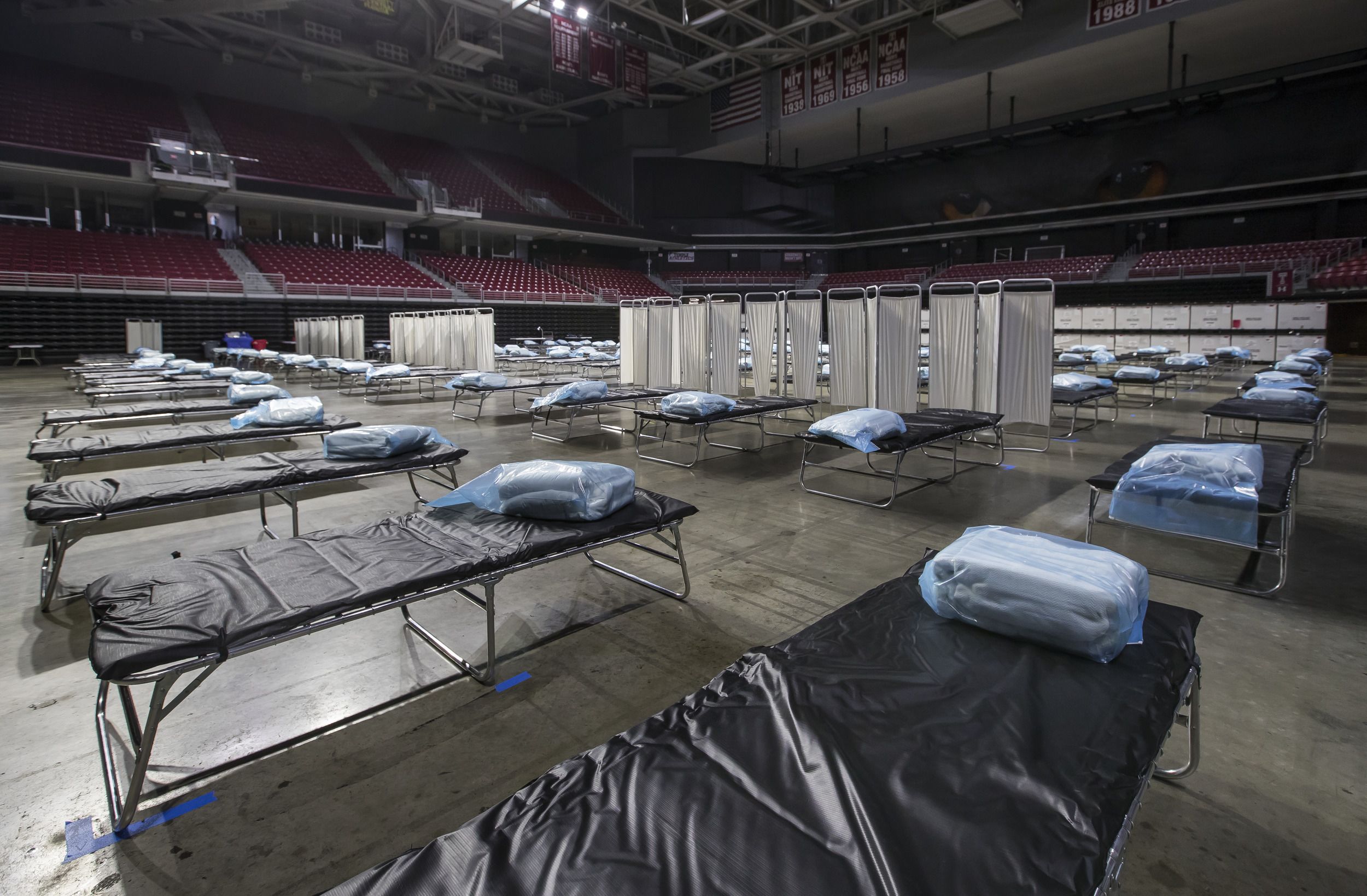

Some people judge college campuses by the beauty of their ivy-covered halls. Temple University has plenty of that, but if an institution was to be judged by a facility, then the structure that best defines the spirit of Temple and its people may be an austere, hastily built and lightly used field hospital, constructed and fully staffed in about 2 1/2 weeks on the cement floor of a basketball arena and disassembled as soon as it was deemed no longer of use a few weeks later.

The name of that structure was as unglamorous as its appearance: the COVID-19 Surge Facility-Liacouras Center (or CSF-L, although most people at Temple called it the Surge Facility or the Surge Center).

It was built in the early spring of 2020 in Temple’s Liacouras Center on North Broad Street on the university’s Main Campus in Philadelphia to serve as a temporary hospital that would help care for a potential surge of COVID-19 patients that the city’s overwhelmed hospitals might not be able to handle.

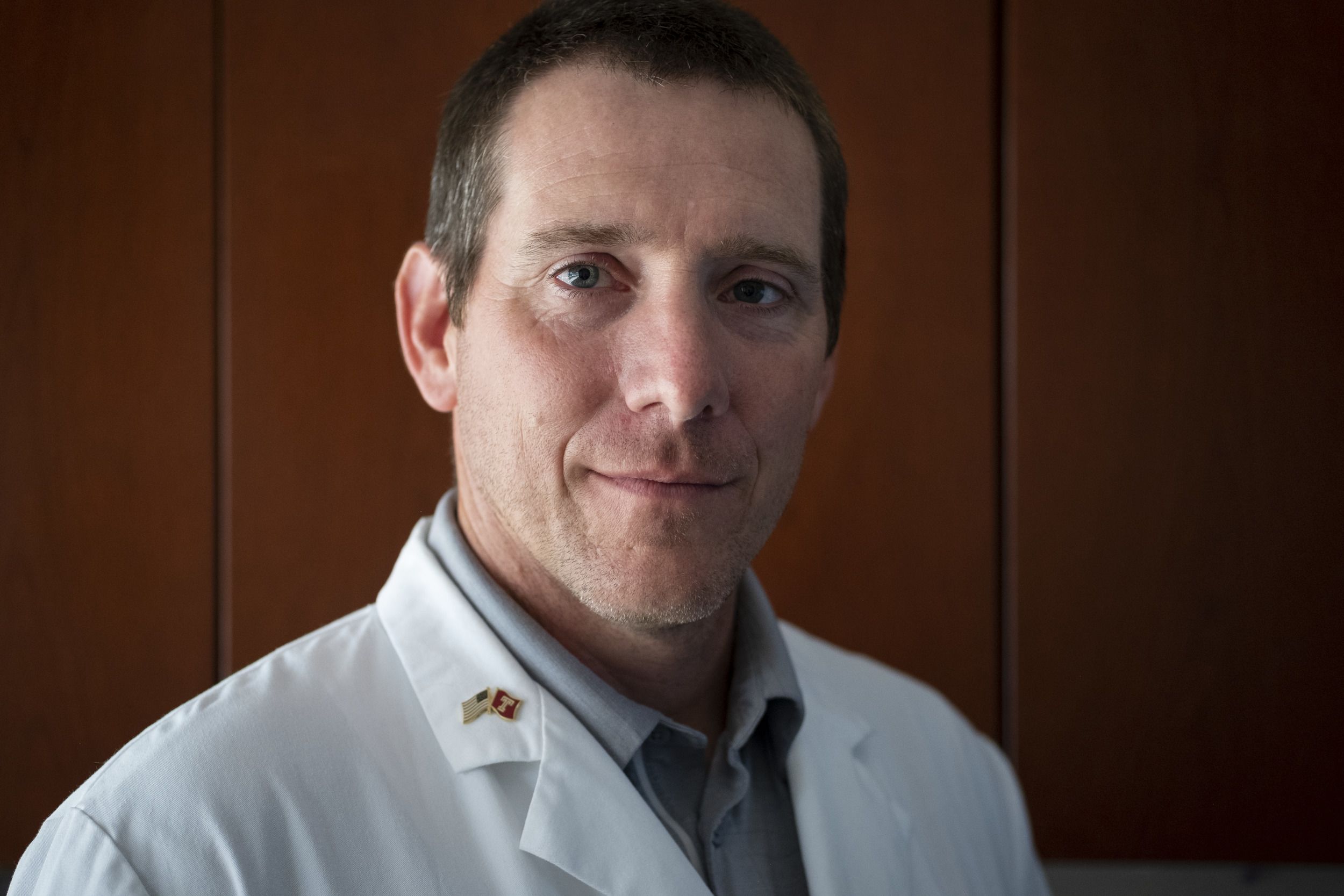

Despite the fact that it’s now gone and most of its 190 beds were never occupied, the Surge Facility’s creation by an army of selfless and creative Temple employees and students working together with federal, state and city authorities, and local laborers may have been the university’s finest hour.

The coming storm

The story of the Surge Facility at the Liacouras Center begins in January 2020, two months before the COVID-19 pandemic made landfall in Philadelphia.

Word of an ominous cluster of pneumonia-like cases linked to coronavirus in China had reached leaders at the Temple University Health System, Temple University and its Lewis Katz School of Medicine. Renowned Temple pulmonologist Gerard J. Criner, chair of thoracic medicine and surgery and Laura H. Carnell Professor of Medicine, had contacts in Wuhan who told him of hospitals being overrun and supplies running short. The Chinese, Criner reported, were building overflow hospitals as part of their response.

Then came the news of the disease’s spread to San Francisco. The Temple team knew there were direct flights from there to Philadelphia. COVID-19’s arrival was inevitable, and Temple Health leadership was already getting the hospital ready, mobilizing dedicated spaces, supplies and staff.

“It was like watching a thunderstorm come across the Plains. You can see it coming from 20, 30 miles away. You watch it get closer, you do your preparation, you batten down the hatches and then you duck and cover, waiting for the tornado to pass.”

Answering the call

To help prepare for the coming storm, Tony Reed—who also served as the official incident commander in charge of Temple Health’s preparation, response and recovery efforts under National Incident Response System guidelines—called together chief medical officers from the city’s other major hospitals and health systems, including Penn, Jefferson, Einstein and Trinity Health, for weekly meetings with the city’s health commissioner starting in February. At the top of their growing list of concerns: Would the city’s hospitals have enough beds to care for COVID-19 patients if cases surged? Hospitals in Philadelphia were already overcrowded in the wake of the closure of Hahnemann University Hospital, which had shut its doors in 2019. The answer, the medical officers suggested, might be opening up a separate facility to relieve pressure during a surge of cases by taking on COVID-19 patients who still needed care but were beginning to convalesce. Moving these patients out of the city’s hospitals and into a special “surge hospital” would create room for more critically ill patients. But where should they create such a hospital? A reopened Hahnemann? Should they convert one of the city’s existing hospitals into a COVID-19 center? Maybe take over a hotel or convention center? The latter was emerging as a promising option, especially given that they could deploy equipment from the FEMA-controlled “national stockpile,” including ventilators and personal protective equipment for caregivers.

By mid-March, cases were on the rise and so was the sense of dire public need. Then came the lockdown. The NCAA college basketball tournament was canceled—a shock to many observers at the time. Why not use an empty basketball arena, the team of chief medical officers thought, like Temple’s Liacouras Center? Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney called Temple Chancellor Richard Englert, then the university’s president.

“The mayor said, ‘I’ve gone to several other entities around the city, and we really need a place for a surge hospital—could Temple do it?’” Englert recalled. “Without batting an eye, I said, ‘Absolutely, we will do it,’ and [Temple Board of Trustees Chair] Mitch Morgan agreed. This wasn’t a time to do an assessment of costs and benefits. We saw it as our duty. We’re Philadelphia’s public university. Of course we’ll do it.”

That was the easy part. Now all they needed to do was turn a gym into a hospital. In just over two weeks.

A giant canvas

Since it opened in 1997, the Liacouras Center—Temple’s flagship indoor arena and the largest indoor facility in Philadelphia behind only the Pennsylvania Convention Center and the Wells Fargo Center—has hosted rodeos; circuses; community dental clinics; rallies by presidential candidates; boxing, wrestling and mixed martial arts bouts; high school and college graduations; concerts; and, of course, hundreds of Temple basketball games. Lee Roberts, senior associate athletic director for facilities and event management, has been there to see it all. He’s proud of how quickly his team can transform the arena floor.

“The main event floor is like a giant canvas,” said Roberts, a Temple employee for 38 years. “We wipe it clean and get it ready to create the next thing. We can go from a rodeo with a dirt floor to Cirque du Soleil, with 21 trucks of equipment, in hours.”

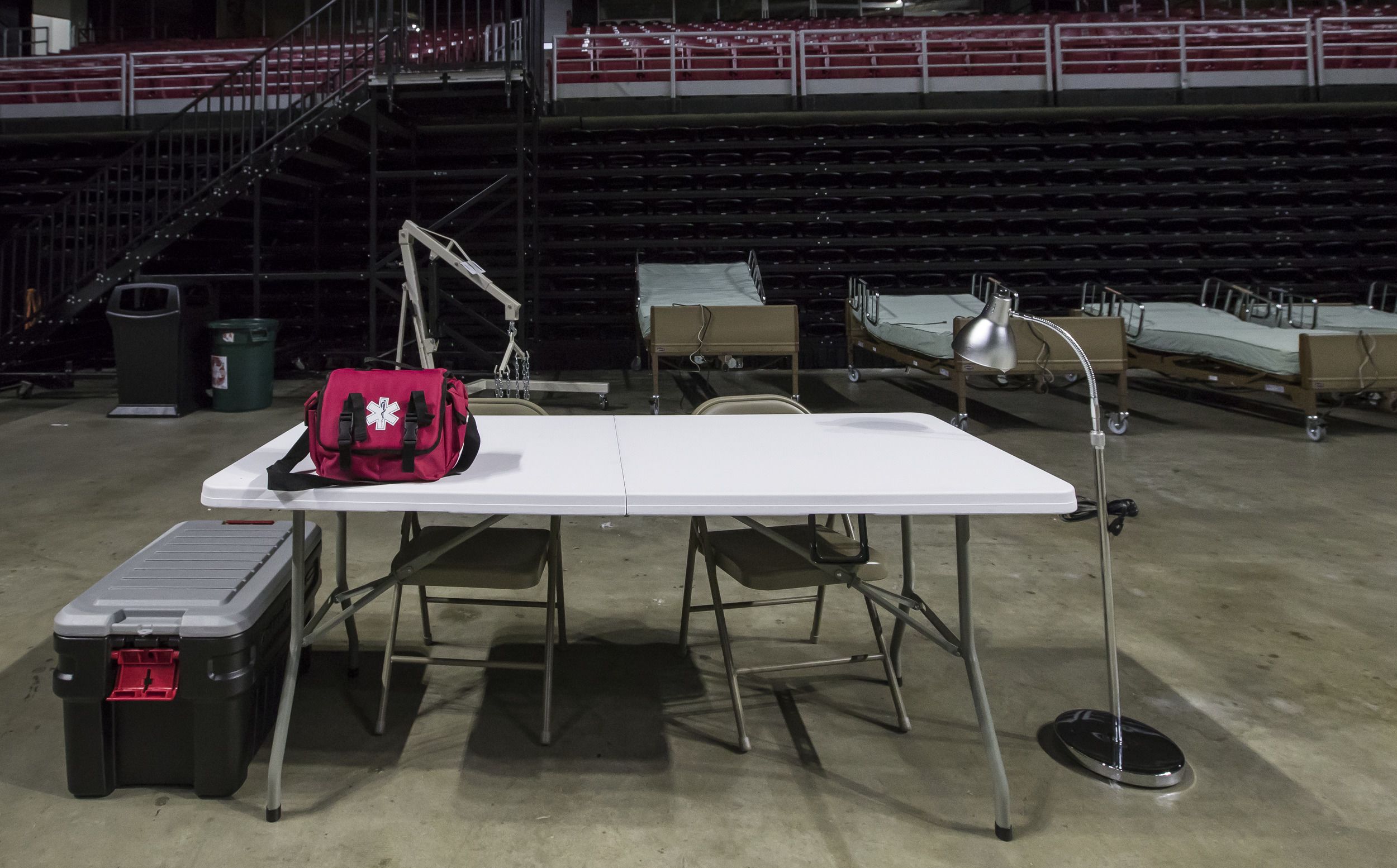

But preparing for a circus isn’t the same thing as morphing an arena into a hospital. A COVID-19 surge hospital needed adjustable beds, linen and laundry services. Air flow that met federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standards for airborne infection control. Oxygen, suction, water, lighting, electrical power and secure access to patient records available at every bed on the floor. A laboratory. Medicines, the technology to deliver them and spaces to store them. Patient transport systems, including ambulances. Personal protective equipment. Security. Wi-Fi. Cleaning supplies. Wheelchairs and walkers. Carts. Food for a wide range of diets and the means to serve it. Ventilators. EKG machines and an X-ray machine. A fire engine ready to go outside the building in case of a fire or explosion. Mobile toilets. Places for patients to recharge their phones. A space to resuscitate patients privately. A morgue.

And although they were building a field hospital on a gym floor, no corners could be cut.

“We tried to make sure that we had the same quality of care and safety that we assure in a hospital setting,” said Christina Rose, a clinical professor in pharmacy practice at Temple’s School of Pharmacy, who put her years of clinical pharmacy management experience in an intensive care setting to work by volunteering to serve as co-leader of the Surge Facility’s pharmacy. “That’s part of what made this so intense. The work needed to be done quickly, but it needed to be done correctly and safely. The stakes were high. It would be catastrophic if a deadly event happened because of an error at the Surge Facility at the Liacouras Center.”

Aria Health President Sandy Gomberg, former Temple University Hospital president and chief executive officer, was appointed CEO of the Surge Facility, and she quickly took the lead, overseeing its creation. At her disposal was a broad group of professionals and volunteers: the Liacouras Center’s staff, laborers with local unions, FEMA staff, the Philadelphia Office of Emergency Management, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Philadelphia Fire Department, and an army of ferociously dedicated Temple University and Temple Health staff and student volunteers from units ranging from Information Technology Services and Student and Employee Health Services to the Lewis Katz School of Medicine.

Creative solutions

In early April, about a week after President Englert agreed to provide the space, the physical transformation began. From the beginning, the Surge Facility’s formidable infrastructure needs posed the biggest challenges—and inspired the most ingenious solutions.

How to deliver oxygen to each patient without using tanks?

“They stationed an oxygen tanker truck at street level outside the Liacouras Center, then local union plumbers came in and literally ran temporary piping—a whole delivery system—to carry oxygen from the truck down to the arena floor to each individual bed,” Roberts said.

How to deliver lines with power to each bed without obstructing the floor?

“We created a rigging system from scratch and flew it above the ground, like we do for a show,” Roberts said. “The union stagehands came and assembled trussing that allowed us to drop down power lines from a flying rig above the beds.”

How to organize all the oxygen, power and other utilities at each bedside without walls to suspend the outlets in?

“When the final beds that we ended up using were delivered, they came in big boxes, so they set the boxes upright between each bed as a support, and all the mechanics for oxygen lines and electricity were run on top of the boxes,” said Dorrit Sterner, MED ’79, a staff physician with Student Health Services with many years of field hospital experience who worked as a volunteer at the Surge Facility.

With limited space, where do you put all your supplies so they’re out of the way but easily accessed?

“A gentleman working with us who did the supply work came up with the idea of using the retractable lower stands surrounding the floor to create natural shelves as a storage system for our cabinets with equipment and supplies—everything from IV supplies to snacks for the patients—without taking up floor space. It was genius,” said Virginia McNally, a registered nurse with Student and Employee Health Services with a ton of ER experience who volunteered to help lead the nursing team at the Surge Facility. “There were so many creative ideas.”

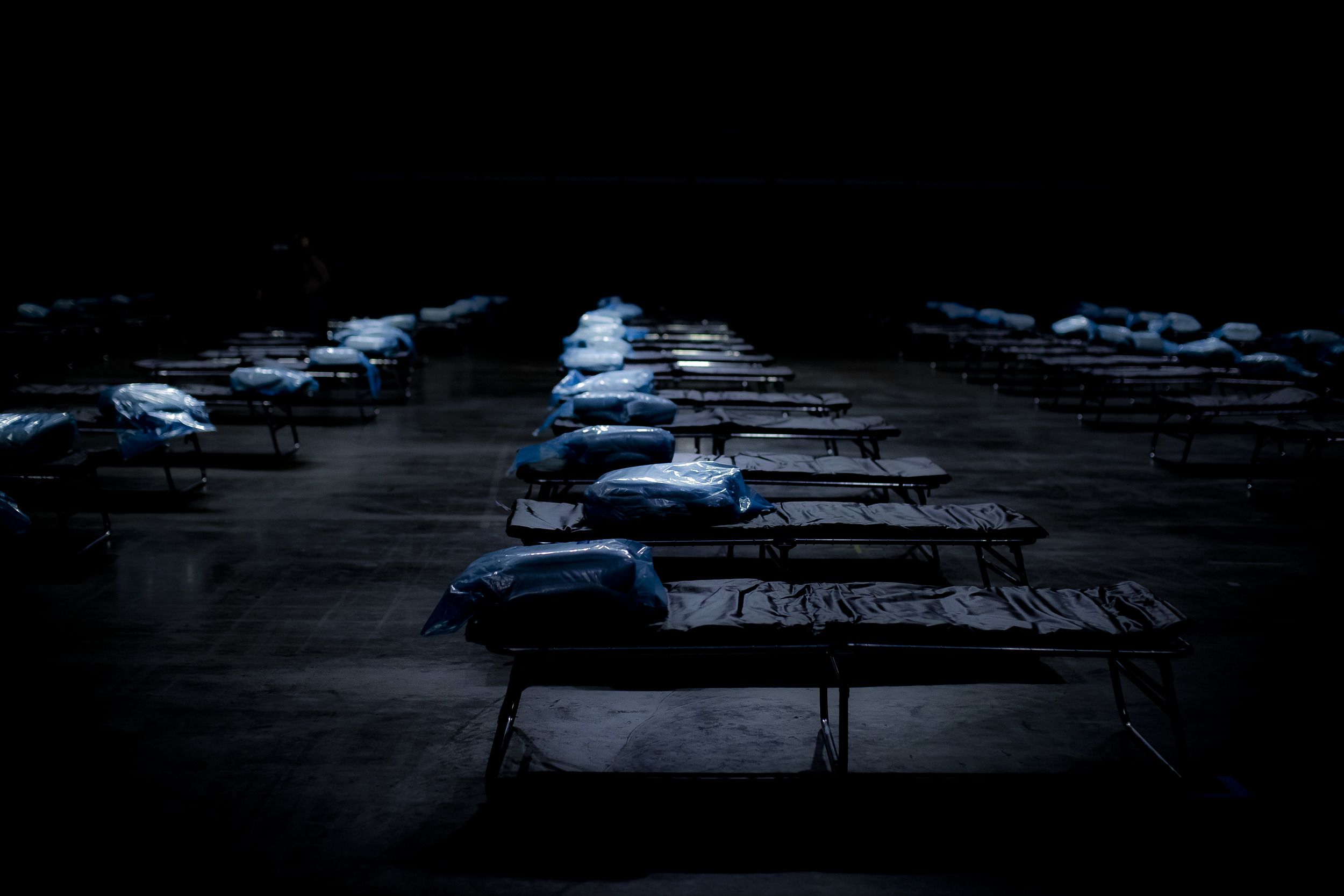

Students to the rescue

Rose, Sterner, McNally and many of the other Temple healthcare professionals who served in the Surge Facility did so because they couldn’t bear sitting on the sidelines in a moment of urgent community need. They had front-line clinical experience, they knew they could help, so they stepped forward.

For medical students at Temple’s Katz School of Medicine, the feeling of helplessness in the spring of 2020 was even more profound—especially for third-years like Michael Creager, MED ’21. Two weeks into his internal medicine rotation and only months from earning his MD, the university pulled Creager and his peers from their clinical rotations and told them they couldn’t go into Temple University Hospital for the foreseeable future. In the weeks that followed, Creager and his peers heard about what was happening at the hospital. Boyer Pavilion, once the site of outpatient offices, had been transformed into a critical care center for COVID-19 patients.

“I remember sitting in my apartment and feeling useless,” said Creager, who has since begun his residency in internal medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “We were about to enter a profession that was about treating disease and caring for patients, and we couldn’t do that. But I knew I could help. I wanted to volunteer, and I knew many of my peers felt the same way.”

That’s when he got an email from the late John Daly, dean of the medical school. Weeks earlier, Creager had pitched Daly on the idea of launching a global health center at Katz, a natural extension of Creager’s involvement in Temple Emergency Action Corps, a student organization founded in the wake of Hurricane Katrina that focused on global health, disaster relief and care in North Philadelphia. Daly remembered Creager’s proposal. He explained Temple’s plans for the surge hospital, and asked Creager if he wanted to volunteer to assist the Surge Facility’s acting chief medical officer, Anthony Colletta.

“I instantly said yes,” Creager said. “I didn’t really have to think about it. There were surge hospitals in New York that were being overwhelmed and I wanted to be in the thick of it and do what I could.”

Creager recruited a few peers, and in the coming weeks they worked with Colletta and Katz School of Medicine faculty members and emergency medicine experts Maura Sammon and Robert Bryan, who came on board to take the lead on clinical care at the Surge Facility, to develop patient transfer protocols, care protocols and much more. Other students signed on and began to work with Sandy Gomberg; they took over the coordination of ongoing student recruitment, developed work flows and supported the Surge Facility’s pharmacy. Eventually more than 30 medical students volunteered at the Surge Facility, providing much of the needed brain and brawn.

“Our medical students impressed the hell out of me—I don't think our project would have gone as well as it did without them. They were so smart, helpful, humble and they’re IT wizards. What would take us dinosaurs forever to put together in the computer world, they just cranked it all out in no time flat. They’re probably the people that I will remember the most from this project.”

An ephemeral monument

On April 16, just over two weeks after the process of construction and mobilization had begun, the Surge Facility at the Liacouras Center opened for patients. The floor of the Liacouras Center looked like a cross between a PC’s motherboard, a child’s Lego construction and an Amish quilt—a complex but orderly arrangement of evenly spaced beds, boxes, conduits, rigging and cables that was almost beautiful when seen from the higher portions of the arena. If you’ve ever looked down on the arrangement of empty chairs on the floor of the Liacouras Center before the procession of Temple graduates on Commencement day, an event that has taken place every year (except 2020, sadly) on this same gray floor, then you understand.

For half a month—a tiny fraction of the time it takes to create a working hospital under normal conditions—hundreds of individuals representing dozens of offices, agencies and institutions put aside their fear of a disease that was poorly understood at the time, begged their loved ones for patience, asked their colleagues to pick up the slack at their regular jobs and threw themselves into building a surge hospital that met the highest standards of health, safety and comfort they could achieve.

There was plenty of stress, and not much sleep (“maybe three hours a night for two weeks,” confessed Rose, one of the Surge Facility’s two pharmacy leads). And yet not a single one of those hundreds of people hesitated to help. They were hungry to serve the city and its residents and take pressure off its hospitals and front-line workers.

“I grew up here in North Philly,” said Roberts, who had already been a Temple employee for more than a decade when the Liacouras Center itself was constructed. “I knew North Philadelphia was being impacted by this disease. Helping the community has always been a point of emphasis since I started at Temple. Yes, there was some fear. But stepping up was the only thing that could be done. It made me feel good. It made me proud that the university stepped forward.”

That sense of pride peaked when the facility opened. Yet no patients were transferred from Philadelphia hospitals that first day. Fifty-eight patients were referred from local hospitals, but in the end only 14 patients were admitted to the Surge Facility. The deadly surge of sick COVID-19 patients never overwhelmed Philadelphia’s hospitals as feared, nor were surge hospitals in many other cities across the nation deployed as anticipated.

With so few patients admitted, cared for and released, was the Surge Facility a success? According to every member of the Surge Facility team, it was a triumph.

“This place is a success even if we never have to use it,” said Sterner.

They pretty much never did. That’s a good thing. And within a few weeks, it was gone, one hopes never to return.

To Reed, Temple Health’s chief medical officer and COVID-19 incident commander, the story of the creation of the Surge Facility proves three things. First, there’s nothing out there that Temple people can’t do. Second, that Temple, as Philadelphia’s public university and the keeper of the city’s closest thing to a public hospital, can bring together broad and diverse groups of institutions—some of whom are normally competitors—to create a collaborative environment.

But what he’ll remember the most is the selfless ferocity of the Temple people who invited the city and its sick onto its campus and built a working hospital on a gym floor from scratch in 2 1/2 weeks.

“Temple is not going to back down from a challenge,” he said. “Sit this one out? Hell no.”

Helping students get clinical experience

during a pandemic

Hands-on experience with real patients is a critical part of many public health degree programs. Although many schools halted clinical placements during the pandemic, Temple’s College of Public Health (CPH) decided to implement aggressive testing and augmented PPE programs for its students. In the past year, more than 1,000 CPH students in programs ranging from nursing to rehabilitation sciences to public health were able to complete their clinical placements—and none got infected. “We responded to the needs of our students,” said CPH Associate Dean Susan VonNessen-Scanlin. “You learn more from human interaction than from any other model.”

When Montgomery County needed mass testing, Temple Ambler came to the rescue

In March 2020, mass COVID-19 testing sites were desperately needed in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia had a site at Citizens Bank Park. Neighboring Montgomery County approached the university for a testing site that would serve suburban residents. With a history of partnership with the Upper Dublin Township and County, Temple stepped forward to offer its expansive Ambler Campus.

Within days, led by Pennsylvania National Guard troops and with the collaboration of officials with FEMA, the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Association, Montgomery County, Ambler Township, Upper Dublin Township and a wide range of Temple units from Campus Safety Services to Facilities Management, a drive-thru testing site the size of two baseball fields was constructed in Temple Ambler’s parking lot.

In addition to providing space, Temple also provided critical IT support through Reid Overturf, assistant director of Information Technology Services at Temple Ambler.

Between 250 and 350 individuals received free testing, by appointment, each day. When it was time to decommission the site, the National Guard troops broke down the facility as quickly as they had assembled it with incredible efficiency and organization. And although the site is long gone, the spirit of sacrifice and cooperation that fueled it is unlikely to be forgotten by anyone at Temple Ambler or the Montgomery County community. Before the last test was administered, neighbors lined Woods Drive with “thank you” signs to show appreciation to the first responders and the university.

“It was an honor to be part of a front-line process,” Overturf said. “The gravity of what we all were doing was significant.”

Also serving on the front line of the testing site day in and day out was Joe Imszennik, manager of facilities and service operations at Temple’s Ambler Campus. “Working with Montgomery County Public Health, the National Guard, FEMA and Upper Dublin Police to set up the test site was challenging,” he said. “But, all members of our Temple facilities team came together, rose to the challenge and provided continuous support to the operation through a tumultuous time.”

Ambler Campus Associate Director Beth Shepard-Rabadam, the liaison between Temple and officials at the testing site, agreed.

“Lives were at stake, and community members were relying on the university to be a good partner. I was very proud to work with my campus colleagues to serve this important community need. I was proud that Temple leaned into the opportunity to serve our host communities.”

How Temple is training

an army of contact tracers

Soon after COVID-19 came ashore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged communities in the U.S. to train people to perform contact tracing, a practice that limits a disease’s spread by identifying and contacting those who’ve come into contact with infected people. But who was going to do that training?

Temple’s College of Public Health (CPH) answered the call, quickly launching a new contact-tracing certificate program that has trained almost 900 people from as far away as California and Italy to serve as contact tracers for public health officials in Pennsylvania and beyond, including Temple’s own contact-tracing unit.

“We reached out to the state and said ‘we’re developing this to assist,’” said Resa M. Jones, chair of CPH’s Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, who spearheaded the program’s creation.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, in order for us to reopen, in addition to mass testing, we needed to have contact tracing,” Jones said. “Even with the vaccines, if contact tracing isn’t done, we risk having outbreaks. We risk more lives lost.”

Open to all, the online, self-paced, 10-hour course covers subjects ranging from the basics of disease to ethics, cultural sensitivity and motivational interviewing. Students perform at least one practice tracing phone call. To register, visit Temple’s continuing education site.